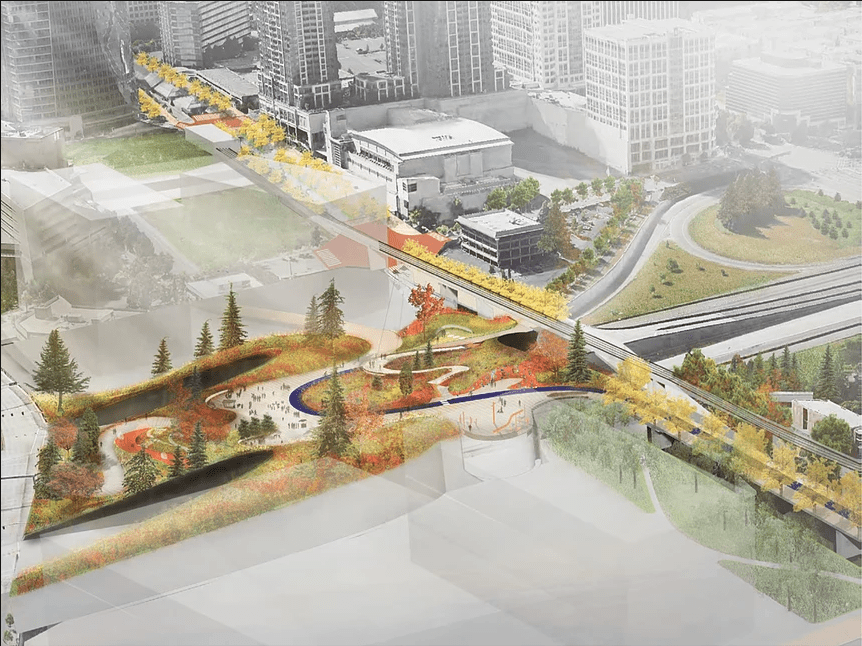

Removing I-405’s NE 8th Street cloverleaf interchange would free up space to extend the planned “Grand Connection” lid northward.

A dozen cars idle before a stoplight; a dozen others rush through the intersection in front of them. The sidewalks are empty today like usual; cars are the only populace on the streets. The light turns green and the cars rush forward in different directions.

I’m standing at the intersection of NE 8th Street and 11th Avenue NE in Downtown Bellevue. To my left and right are brand-new skyscrapers—the gleaming manifestation of Bellevue’s immense growth over the last twenty years—and before me is a freeway interchange connecting 8th Street with I-405. Nowhere else is the stark contrast between the 20th and 21st centuries more apparent: floors of dense development and acres of empty, car-centric land smacked right next to each other.

It’s quite a scary experience to walk (or bike) across I-405 on NE 8th Street. Traffic speeds by at highway speeds on the street’s six wide lanes while pedestrians are confined to a narrow sidewalk. Cars taking the freeway entrance seem to have no regard for any speed limit whatsoever. I’ve often found myself trekking across I-405 on other streets since 8th Street is really that daunting—pedestrians and bicyclists need to traverse no less than six treacherous crosswalks just to get from one side of the freeway to the other.

The fact that the interchange still exists is a testament to Bellevue’s unequivocal love for autopia. Downtown streets are huge—twice as wide as their Seattle counterparts—blocks are long, and sidewalks are afterthoughts. No matter what the tall buildings may entail, Bellevue is still a car-dependent suburb at heart.

Picking up the pieces

Bellevue blossomed at a time when criss-crossing cities with highways was the hallmark of urban planning. Six-lane avenues, ten-lane freeways—the more lanes the better. It was a time when automobile ownership was booming and when global warming wasn’t really a thing.

But those dreamy days of Pax Americana remain only a distant memory of our turbulent present day. Global warming is now threatening the basis of our very livelihoods, not least because of the unsustainable lifestyles of days gone by. We’re starting to feel the squeeze of those car-oriented policies in other places too: driving is deepening structural inequalities, many cities are seldom walkable, and public transit is lacking. The dangerous health effects of driving puts communities within one-thousand feet of freeways at high risk for fatal diseases like asthma and respiratory illness.

As we build our cities for tomorrow, we must not surrender ourselves to the playbooks of yesteryear. Do we really need to preserve the 15 lanes of freeway rammed through Downtown Bellevue? Can we do without the enormous interchanges that prevent our cities from developing sustainably?

Bellevue is taking steps to become more friendly to our friends on foot, such as building pedestrian malls, widening sidewalks, and even lidding a portion of I-405. But these efforts are still pretty car-oriented, to say the least. A larger freeway lid, as I’ll describe later in this piece, would take a bigger step in the right direction.

Induced Demand: More Lanes, More Traffic

Rather than attacking the root cause of the issue—freeways themselves—many urban planning projects try to work around them without really questioning whether they need to be there in the first place. Projects shouldn’t be dinged for reducing traffic speeds or capacity, since in many cases such reductions are beneficial.

More lanes doesn’t equate to less traffic, in fact just the opposite. Induced demand dictates that while road widening will decrease congestion in the short-term (since there’s more lanes handling the same number of cars), it won’t speed up travel times in the long-term. That’s because as traffic thins, people will take notice and use the road more and more until it becomes just as congested as before. Think of it this way: you wouldn’t drive from Seattle to the Seattle Premium Outlets in Tulalip after work—the mall would be closed before you even arrived! But if the traffic wasn’t as bad, you might have made the journey. Commuters might also stop taking the bus or carpooling when they see that the HOV lanes aren’t much faster than the regular ones.

Texas learned this the hard way after spending $2.8 billion to expand its Katy Freeway to a whopping 26 lanes in Houston. After the expansion, rush hour travel times increased by 51%. More cars simply filled the extra capacity the road provided. With this in mind, it’s important to be open to change when discussing how we shape our roads and cities. Downsizing roadways isn’t always a bad thing.

Though this isn’t to say that we should just get rid of all roads—there needs to be a balance. I-405, being an important regional connection without nearby alternatives, should definitely exist so Eastside residents can still get around. That being said, there are certainly parts of the freeway that can be slimmed down, particularly the 8th Street interchange.

The monstrous interchange consumes more than 25 acres of land that’s close to hospitals, malls, and transit. And being a freeway, I-405 naturally acts as a giant growth barrier for Downtown. Highrises loom to the west, and strip malls line the avenues to the east. While being no more than a few hundred feet apart, the different sides of the freeway are two very different worlds.

Bellevue’s Lid and Freeway Plans

The City of Bellevue has an ambitious plan to bridge this gap by lidding a portion of I-405 from NE 6th Street to NE 4th Street. It’ll improve pedestrian access across the freeway with a multi-use trail along the light rail guideway and provide green space with a landscaped park atop the freeway’s right-of-way. The Bellevue City Council selected a preferred lid alternative in 2018, but hasn’t yet identified or allocated funding. The City study projects the lid will cost between $116 million and $130 million.

But there are flaws. The two giant freeway ramps shoved through the lid’s southern end mean that more than a quarter of the lid is barely usable. The trees hiding those ramps then take up another chunk of land, and the whole lid has awkward hills to conform to the 6th Street ramps. Plus, with only three connections to the outside world, the park itself is extremely isolated.

If anything, this lid wasn’t built to satisfy pedestrians but rather developers. Without good integration into the rest of Downtown, it’ll be unlikely that the lid will attract much use, and without changes to the nearby road network people will still be discouraged from walking.

Map of the proposed “Grand Connection” lid over I-405 (City of Bellevue /Balmori Associates)

Could the lid just be another attempt to greenwash highway expansion? The Washington State Department of Transportation is adding two toll lanes on I-405 from Bellevue to Renton and the City is planning to build yet another freeway interchange downtown.

Both projects masquerade themselves as congestion-reducing improvements, but these “Lexus Lanes” and “concrete dragons” will do anything but. Expanding I-405 will only create more traffic and more pollution—hardly a good idea in the midst of a climate crisis—and building new interchanges always hinders walkability.

The whole debacle bears a striking resemblance to the proposed Rose Quarter Freeway “lids” down in Portland which many have also accused to be an attempt to greenwash widening I-5. Like our I-405 lid, Portland’s lids don’t add much useful park space nor do they substantially benefit the community.

Both the I-405 lid and Portland’s lids are simply too reactionary. By trying to marry an urban park with a freeway expansion, they end up not serving the needs of anyone very well. The money spent to expand the freeway could be invested in transit to reduce commute times and there’s certainly better ways to build quality urban spaces residents will actually enjoy.

Think about it: how much cheaper would the I-405 lid have been if it didn’t have to constrain itself to fit around the existing freeway ramps? Why is it so tiny and have so few outside connections? And wouldn’t the enormous cloverleaf just to the north kind of blow the whole point of having it in the first place?

Upward mobility

We must not be afraid to change the status quo. Reducing road capacity is not only beneficial to the environment but it opens up opportunities for urban revitalization that would have been unheard of otherwise. It’s time for us to reclaim the land that freeways stole from us, and Bellevue has tons.

Removing the 8th Street interchange is a great place to start. It’s loud, pollutive, and treacherous for pedestrians. It’s the antithesis of what a modern, walkable city should be; a relic from ancient times that must go.

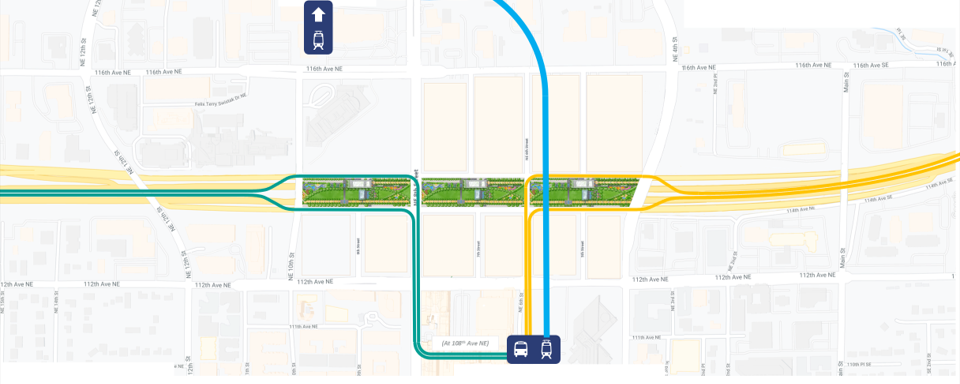

We’ll keep the 8th Street alignment over I-405 but remove the ramps connecting the two. While we’ll be reducing the overall capacity of the freeway, drivers can still get where they need to by using the ramps at NE 4th and NE 10th Streets (more on this later). It’s questionable that Downtown Bellevue has the number of interchanges it has in the first place—Seattle doesn’t even have as many ramps in this short of a stretch—so downsizing won’t cause a carmageddon. What’s more, the “cloverleaf” design of the 8th Street interchange is unsafe and outdated, causing higher risks for collisions between cars and pedestrians alike.

With the ramps gone, pedestrians will enjoy quicker, safer access between the east and west of I-405. There’ll likely be less cars driving around with the reduced capacity, meaning fewer emissions. But it’s only good, not great; the freeway itself will continue to divide its two sides and stifle development nearby.

The Vision Realized

Many cities across the country have built lids upon freeways and created quality urban space atop them. Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park atop a freeway has become a popular community gathering place and a prime location for events, and Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway buried a massive viaduct and replaced it with miles of trees and green space. And let’s not forget the many lids we have right here at home: Aubrey Davis Park, Sam Smith Park, the 520 lids, among others—it’s hard to imagine what the landscape would look like without them.

The City of Bellevue was on the right track with its I-405 lid but tried too hard to design it around existing road infrastructure. Little quality space was created, and much of the lid space was unusable. Lid parks needn’t be overdesigned; people shouldn’t have to navigate an obstacle course to get from one side to the other. A large lawn to relax upon, benches to read on, and trees keep things cool are all people really need. The occasional plaza and nicer landscaping are always appreciated, but the basics always come first.

These distinguishing features are what make Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park and Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway so much more enjoyable than our Freeway Park. The former are easily accessible and are spaces we’ll actually enjoy while the latter is neither.

If Bellevue’s I-405 lid wants to fall in line with the former, it’ll need to be a lot larger and much more open. It’s possible—as long as the nearby ramps are removed.

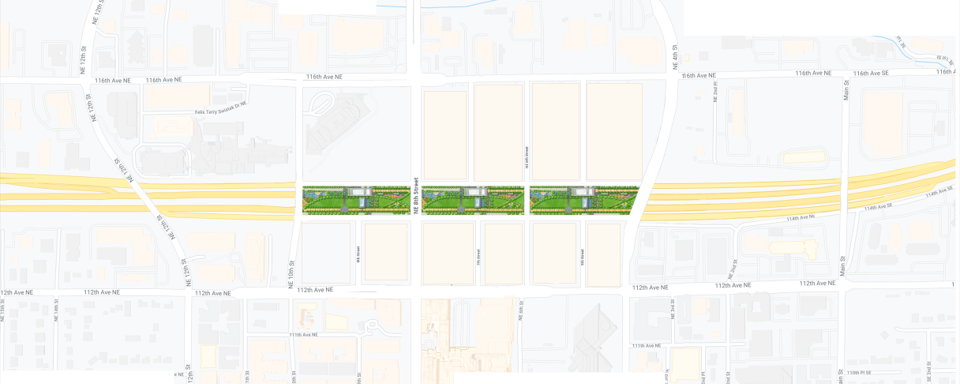

The new lid would stretch from NE 4th Street to NE 10th Street and cover most of I-405’s downtown portion. Local streets would be reconfigured, with the entrance to northbound I-405 and exit from southbound I-405 being moved north to 10th Street, and the entrance to southbound I-405 and northbound exit from I-405 being moved to 4th Street. The HOT exits at 6th Street would also be relocated to 10th and 4th Streets to join their mainline counterparts.

Two new avenues will each run on an edge of the lid and act as frontage roads of sorts, and they’ll include a bus lane to accommodate buses and BRT. These avenues provide other benefits, too; they create a clear zone between private buildings and the lid, making the park feel more public (setting a building right on the edge of the park fosters a sense of ambiguity between those living in the building and outsiders).

As for the lid itself, things should be kept simple enough to be enjoyable while also featuring adequate landscaping to be appealing. Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park is very good at this so let’s use it as our blueprint. Remember, we’re not reinventing the wheel here–sticking with the tried and true is the way to go.

At about 2,000 feet long and 300 feet wide, our lid has 14 acres for large grass lawns, tree-lined trails, children’s playgrounds, and a dog park. Perhaps a pavilion could be added near the center to host events, or a volleyball pit could find a home near the southern end. There’s so much potential for this new space–I bet the community and you, dear reader, have great ideas for what it can become!

Lids themselves have inherent benefits to the community, too. In a 2018 study, the American Journal of Public Study found that lids offer health benefits to residents nearby thanks to access to green space, exercise opportunities, and reduced noise and pollution.

Most importantly, our lid will help reconnect Downtown Bellevue to Wilburton and spur redevelopment of the area’s strip malls. Guided by light rail, they can become walkable transit-oriented development, potentially providing over 20,000 housing units–and many of those can be affordable. But only by creating a pedestrian-friendly crossing of the freeway will the city feel cohesive enough to be livable. The crossings right now are not nearly enough.

The Nitty Gritty

Of course, a megaproject like this comes at a price. A conservative estimate puts the cost to build a lid at $22 million per acre, putting the cost of our lid at about $308 million. Reworking the existing ramps might tack on an extra $50-100 million (though this is just a ballpark estimate), so our grand total is about $400 million.

Though it seems eye-watering at first, the price isn’t out of reach. Freeing up the land being used by freeway ramps could immediately generate some $450 million, fully funding the lid. And it’s all smooth sailing from there–with increased land values from the lid, developers will be enthusiastic to pitch in. About 48% of Dallas’ lid was funded by private donations and we could seek to follow in those footsteps. We could even mandate inclusionary zoning as a contingency for developing near the lid and create thousands of affordable housing units. And the lid could even play a part in recovering from the current recession; highway and park projects create some 20 jobs per million dollars invested, making the lid an excellent candidate for government stimulus funding. With all the investment generated, a larger I-405 lid could improve the City’s long-term finances while simultaneously bettering people’s lives.

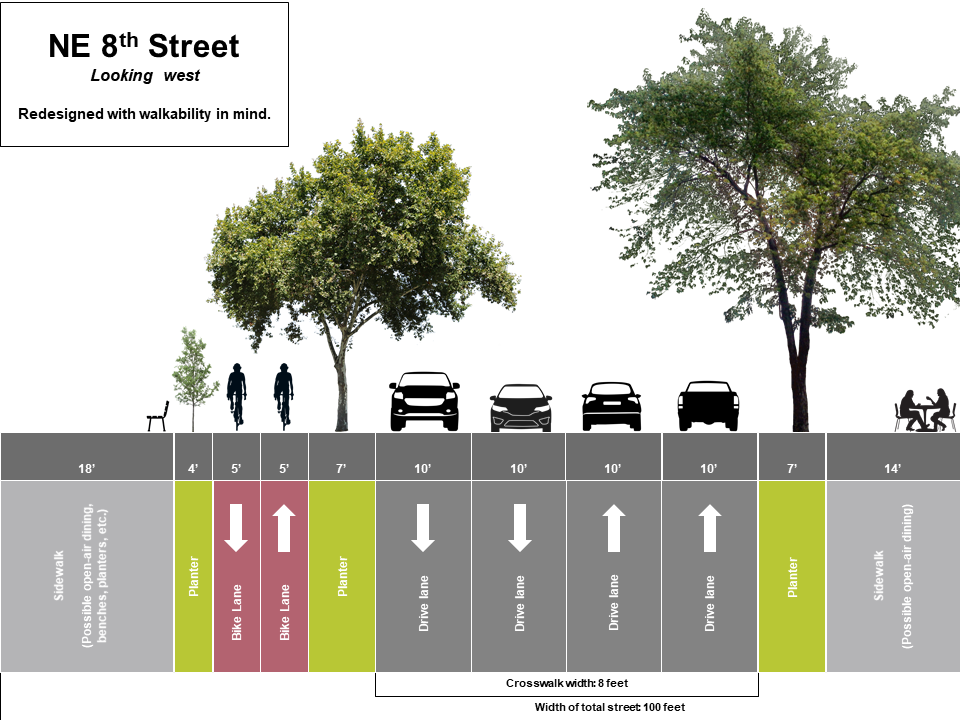

As icing on the cake, 8th Street can be redesigned too since it’s been liberated from freeway duty. The main roadway can be narrowed, bike lanes added, and sidewalks expanded to promote biking and walking. We’ll add room for on-street dining and benches, and street trees can get more space to grow taller and provide more shade, making street life more pleasant.

Alas, there are so many things we’ll need to do to build a walkable, bikeable Bellevue. So many projects that need to be built, so many roads that need to be redesigned. And with these changes come discomfort: we’ll have to change the places we go to and how we get there. It’s daunting, to say the least.

But Bellevue is proof that big dreams still can come true. In less than a century, Bellevue has transformed from a sleepy town to a burgeoning crossroad of life. There seems to be a new skyscraper topping out every time I look up and the foundation for another one being dug every time when my eyes come back down.

I’m taking little steps to cross I-405 on 8th Street; cars rush by me towards the looming Downtown just ahead. Instead of slogging across a speedway atop a freeway traffic jam, maybe one day I’ll be able to take my little steps on a lid teeming with life—what Jane Jacobs called the intricate sidewalk ballet—but for now it’s all just a dream. But it’s a powerful vision nonetheless; let’s take our steps in that direction.

Check out the Downtown For People website for more on the efforts to block the expansion of I-405 interchanges in Downtown Bellevue.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared under the pseudonym byline Hyra Zhang. Brandon Zuo is the same author.

Brandon Zuo is a high schooler and enjoys reading about urban planning and transportation. They enjoy exploring the city on the bus and on their bike. They believe that income and racial equality should be at the forefront of urban development. Brandon Zuo formerly wrote under the pseudonym Hyra Zhang.