Here’s the problem. Sitting through a presentation about the Ballard Interbay Regional Transportation (BIRT) Study, one finds themselves cheering for terrible options.

The issues are implacably difficult and balancing interests is complex beyond imagining. Interbay has a dozen bridges that are not earthquake or climate change ready sitting at the intersection of rail and water. Three very powerful and wealthy communities overlook the neighborhood. Every level of government has a finger in the pie, often crossing political boundaries. Cutting-edge industries share space with the legacy companies that built this city. Everything must keep moving at the same time all of it needs replacement and upgrading.

Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and their consultants at Nelson Nygaard have culled a list of transportation improvements from two decades of Interbay planning studies. The projects range from painted pavement to half-billion dollar bridges. Together, these options are being wound into blueprints for the next two decades of development.

And we are still left asking “is this it?”

Yeah, That’s It.

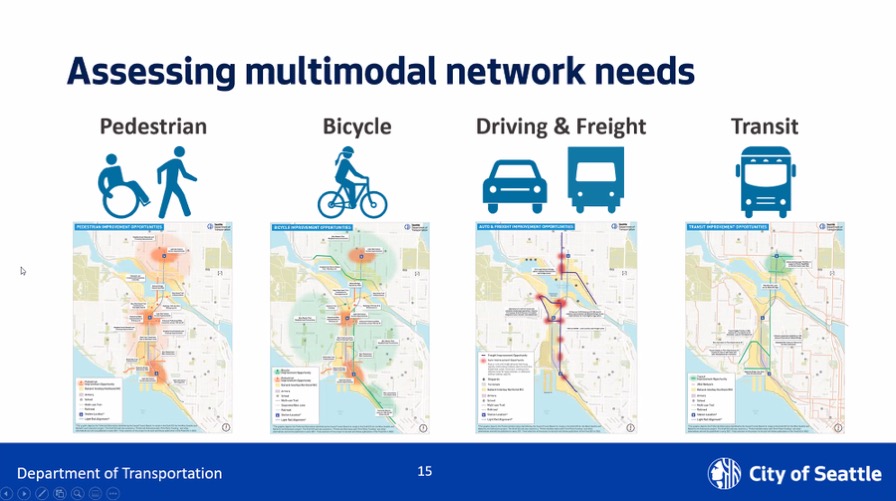

On Wednesday over Zoom, the BIRT project team presented a handful of slides about potential projects in four categories: Pedestrian, Bicycle, Transit and Freight, and Corridor-Wide. Under each category, there was a breakdown of examples, like the Emerson Street Pedestrian Bridge and Freight and Transit Lanes between Denny and Market.

The Multimodal Needs Report has a more thorough breakdown of the proposed projects. (Nowhere are the projects combined into a single table.) Pedestrian projects focus on access around the new light rail stations, trail connections, shared use paths along the bridges, and sidewalk improvements throughout the area. These are echoed in the bike improvements with the additions of completing neighborhood connections and the Missing Link of the Burke-Gilman Trail in Ballard.

The report punts on the transit network connections. There are the future light rail stations as a backbone, with a handful of bus-only lanes supporting them. Busses ride on the same routes as cars and trucks, so the attention goes to roads.

And that puts the most money and effort on the freight and automobile improvements. This is where the two bridges come up. The study includes two of three scenarios for the Ballard Bridge: the low span that simply replaces the bridge at its existing height; and a mid-height span that is still a drawbridge but needs fewer openings. The mid-height bridge lands further north in Ballard and requires extra off-ramps. Off the table for this analysis is a high fixed bridge.

Of interest to most respondents on the call and source of the most questions and comments, the Draft Plan considers two options for the Magnolia Bridge replacement. There is the $400 million 1:1 replacement of the bridge in its existing location. The second scenario is a less extravagant Armory Way bridge that likely would serve people walking, rolling, biking and riding transit better. The scenarios will not examine the Dravus-Only or Low Bridge options from the Magnolia Bridge report.

Other transportation projects include intersection turning radius changes at some locations, joint bus and freight lanes, and access improvements between the Ballard Bridge and Leary, Emerson, and Nickerson.

Next steps for BIRT include testing these proposed projects against four project goals:

- Improve mobility for people and freight

- Provide a system that safely accommodates all travelers

- Advance projects that meet the needs of communities of color and those of all incomes, abilities, and ages

- Support timely and coordinated implementation

It’s here where the fine print starts screaming. Under “timely and coordinated implementation” is “maintain the current and future capacities of the Ballard and Magnolia Bridge replacement alternatives.” The only appendix for the report is the discredited intersection Level of Service analysis that supports automobile dependence. All this bike and pedestrian stuff, and this is a report about cars.

When we start seeing that weird tailoring of the question, we also start to see glaring omissions. Many of the feeder reports dealt with land use, which is one of the most important determinants of traffic generation. But nothing in this report does. The report omits mention of baseline plans like the 1998 Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Centers (BINMIC). When asked, the consultants said that was outside of their timeframe of 2000-2019. However, the BINMIC zombie plan is on every map in the report and referenced in each of the documents that the team reviewed. The freight and corridor-wide projects rehash many of the BINMIC’s incomplete transportation improvements.

Most egregiously, nowhere does the report mention improvements to the two most important pieces of transportation infrastructure in the study area: the Ship Canal and the BNSF heavy rail lines. The study area cuts off at Expedia, just north of the Terminal 86 grain silos. More grain moves from rail to ships through those silos than the Port of Seattle moves fish, vegetables, and fruit combined. The value of those exports rivals the value of Boeing’s exports.

But when the study discusses “freight,” they just mean carbon spewing truck traffic that has to widen roads through the rest of the city to get to an interstate. More climate-friendly freight rail is barely considered.

Those Sweet Federal Dollars

And that’s how we find ourselves cheering for terrible projects. The goal here is to get enough projects together that we can meet a threshold. As Councilmember Dan Strauss mentioned when he joined the second half of the call, “When we package these projects together, it allows us to meet the criteria for federal funding. We can be ready for the next state funding package.”

Really, the idea of building a bridge from Armory Way to Magnolia is expensive and demonstrably awful. But it is vastly better than overspending on a replacement traffic flyover for a minor arterial that only serves 13,000 cars a day. And having it ready for federal dollars means slightly less overspending locally.

Replacing the Ballard Bridge with the exact same is also terrible. A few feet higher, and the bridge could accommodate most boats and reduce a ton of openings. But since we are accepting earlier plans that set the location of the Emerson-Nickerson interchange in stone, the north end of a higher bridge causes all sorts of problems going further north into Ballard. Thus hooray low bridge. Put it on the list, even with the Gordian knot at the south end. We might get the feds to pop for a walkway overtop.

If that sounds ridiculous, that’s because it is. Pushing ahead with a bunch of bad projects is still a bunch of bad projects.

And that is even before we get to the deeper equity issues of relying on old plans. No zoning boundary in this city was set magically. Interbay has been industrial for many years. It’s even shown in white (non-housing) in the 1930 HOLC Maps that codified redlining in Seattle. While there did not seem to be anyone on the Zoom meeting actively chanting for the return of redlining, we have never dealt honestly with its effects on our city. That includes the extensive protection of single-family housing in neighborhoods like Magnolia and Queen Anne at the expense of neighborhoods like Interbay.

There is not a single switch that will fix Interbay, even if that switch turns on federal money. At the moment, we are not even asking the question of what we are fixing. Is it traffic? Or infrastructure? Or a hundred year old legacy that we just really don’t know what to do with?

The Ballard Interbay Regional Transportation study will have a second online meeting on Thursday, August 6 at 6:30pm. Sign up here. Voice your opinion in a survey on the proposed priorities. Send an email with questions to let them know you expect better than cursory highway widening.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.