Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now are making a big ask. Their plan to reduce the Seattle Police Department budget is bound to be an uphill battle, even when a pandemic doesn’t bar in-person meetings. But the groups tried to do just that during a Community Teach In. With speakers and slides, they took 500 people through the history and goals of the movement. As with so much these days, it was done over Zoom and Facebook.

More than just advocacy in the time of Covid or ending militarized policing, the alliance of groups is trying to remake the budget process. Their advocacy for a “just budget” goes beyond public input and demands public participation. The groups are trying to dismantle racism, violence, and bureaucracy all at the same time.

It is a heavy lift. The exclusive pipeline of mayoral budget submission to City Council approval is the hallmark of our “strong mayor” structure of government. To unprepared ears, a participatory alternative sounds like cacophony. “We at a place where there are many people speaking in our movement,” says Nikkita Oliver, attorney, activist, former Mayoral candidate, and opening speaker at the Community Teach In. The key is “understanding that the movement is about the many voices and many solutions coming together for one abolitionist vision.”

But it is not just the budget process and political voting that stands in their way. Stepping outside the boundaries of polite political discourse allows the willfully ignorant to portray “different” as “bad.” The movement to defund SPD faces structures of government that formalize polite political discourse and, therefore, inertia.

Participatory Budging

While dollar amounts and percentages get the top headline in most discussions, participatory budgeting is the cornerstone of Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now’s plans to remake public safety in Seattle. If the police department is doing too much, how does the community decide which programs will be more effective in those roles? According to Decriminalize Seattle’s Jackie Vaughn, that decision making requires “deep outreach and engagement, especially in communities that have been historically over policed and are furthest from the resources and decision making power.”

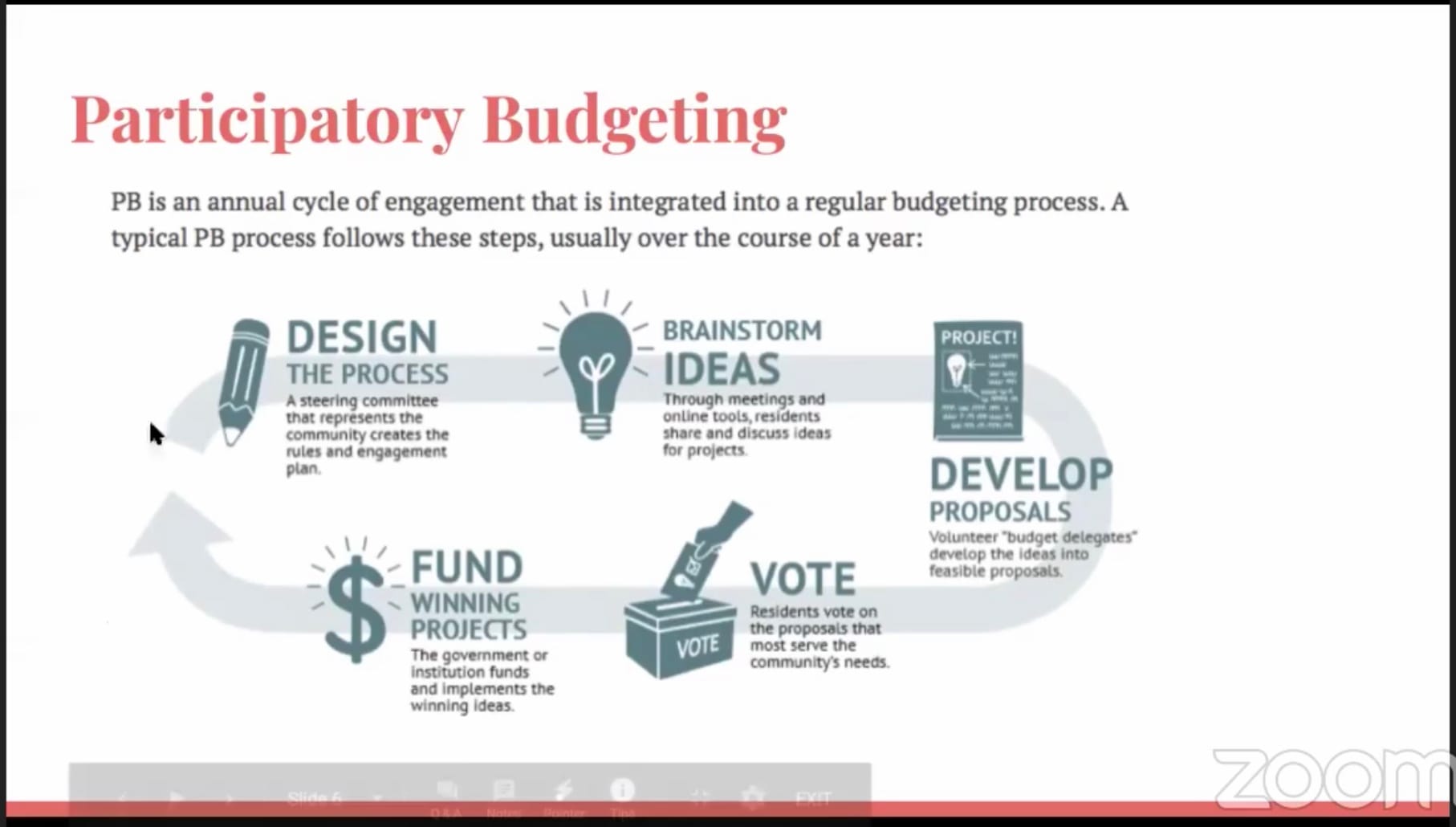

In the process advocated by Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now, participatory budgeting is an annual cycle of feeding new ideas into the budget. The community develops an engagement plan to get residents brainstorming ideas for programs. These programs develop into proposals that the residents then vote to implement. Winning projects get funded.

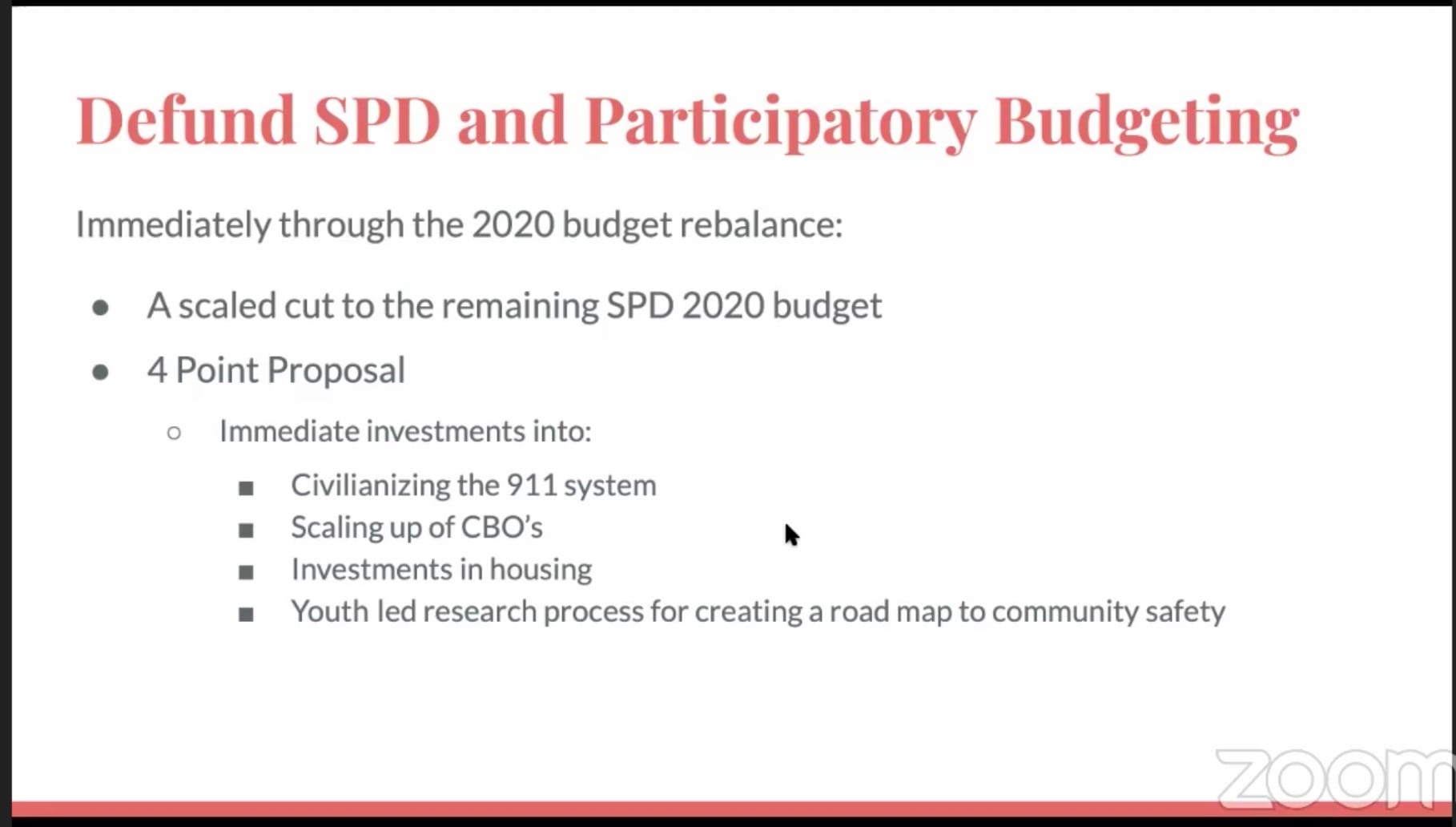

The programs don’t come out of the air. The groups’ four-point plan lays out the areas from which programs will be drawn. Each point creates a pool of information about gaps in our system and effective responses.

Civilianizing 911 means pulling the emergency response system out of the police department. The immediate benefit is to end the gatekeeping that sends armed police to even the most mundane calls. According to Shaun Glaze of King County Equity Now who analyzed publicly available information about 911 calls, “the data does not support the level of funding that we see for the Department.” The majority of calls are traffic and “suspicious circumstances.” Of the non-traffic calls, they estimate 40% could go to a non-police organization. They propose to take 911 data and use it to identify community health and safety issues for an area, then identify the non-police organizations that are meeting those needs.

Community Based Organizations (CBOs) could become the responders to such 911 calls, which is why “Scaling up” CBOs is the second point in the groups’ plan. Sherae Lascelles, founder of the Green Light Project and The Urbanist’s endorsee for LD43 explains it. “You know which auntie or friend to call when you’re having a problem in your life. You’re having a bad day or a meal. Calling the cops is out of the question… Imbue the organizations under this model with the tools to be able to respond, we can meet people where they’re at, address their immediate material needs, and prevent things from escalating to the point of they’re needed and armed response.”

They point to the Trusted Messenger program from the Washington Census Alliance. An infrastructure of people and organizations already exist in Black and Brown communities. There is a trust from having been in the same situation and having the same lived experiences in the community that allows a deeper connection and better service than a municipal office. The challenge is that these individuals and groups do not have the resources to scale staff, volunteers, and programming to meet the community’s needs full time. This network becomes a pool from which participatory budgeting projects can be developed.

The third point, housing, is almost self explanatory. As Vaughn puts it, “People experiencing housing need and survival needs get the police called on them. One way to reduce the need and number of police responses is to actually just meet the needs they have. We need to actually invest that, preventative things we can be doing to not rely on police to solve social issues.” Projects to address these needs are already high on the list for receiving restructured police department funds.

Finally, research. The groups propose to pay youth to find out what safety looks like in their communities. This involves engaging the young people to go out into the community for interviews and networking. The produced ideas will support the brainstorming and project development in the 2021 participatory budget process. One bonus is that research will be done by the young people that don’t have other work this Covid summer.

According to proponents, these steps breakdown the gatekeeping to information and capacity. They open up the police department’s books and inform the development of programs for the participatory budgeting process in 2021.

That still leaves readjusting the budget for 2020, where lockdowns have triggered a budget shortfall. Here the speakers get into percentages, but not necessarily the ones you’ve heard. The groups recognize that SPD has spent money up to this point in the year, so they’re not talking about halving the approved budget. They propose a 12% cut to the budget each month for the rest of the year.

Block the Budget

In many ways, a revised method of budgeting is terrifying to anyone that’s been even remotely affiliated with a municipal budget process. It brings up questions of unspecified objectives, project uncertainty and employee churn. However, given the state’s thousands of untested rape kits, the current system doesn’t seem to be working either.

Vaughn is direct about why these funds should come from the police department: “It only makes sense that we start with defunding the SPD because of the extreme amount of funds that they have had access to and it is an institution that is not working and causing violence in our communities.”

But calling for a change in budgeting culture at the same time as calling for a change in the budget can sow confusion. It allows Mayor Jenny Durkan to make the disingenuous argument that there is no plan.

This isn’t new. Bad faith actors have long weaponized the community input process against beneficial projects and neighborhoods of color. In just the last few years, Seattle has seen town halls descend into hateful shouting matches, environmental impacts turned against critical pedestrian infrastructure, and litigation stall affordable housing.

What is new is that the gaslighting and obstructionism is coming from the City’s executive office. Mayor Durkan is asking us to not believe our lying eyes. It’s a Seattle passive aggressive way of asking “why don’t the Black folks march against all those murders.” By saying the advocates of defunding have no plan, Mayor Durkan doesn’t just deny the outreach and public education by groups like Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now. She also asks us to not see the thousands of small or unofficial organizations that tie communities together.

But Mayor Durkan’s blame shifting would not be as effective if we didn’t have some expectation of “regular” processes. It is being parroted by local business groups. Even in the time of Covid, there is a perception of what governance looks like. That look is is demure, formal, and predominately White.

Propriety and High-Minded Sausagemaking

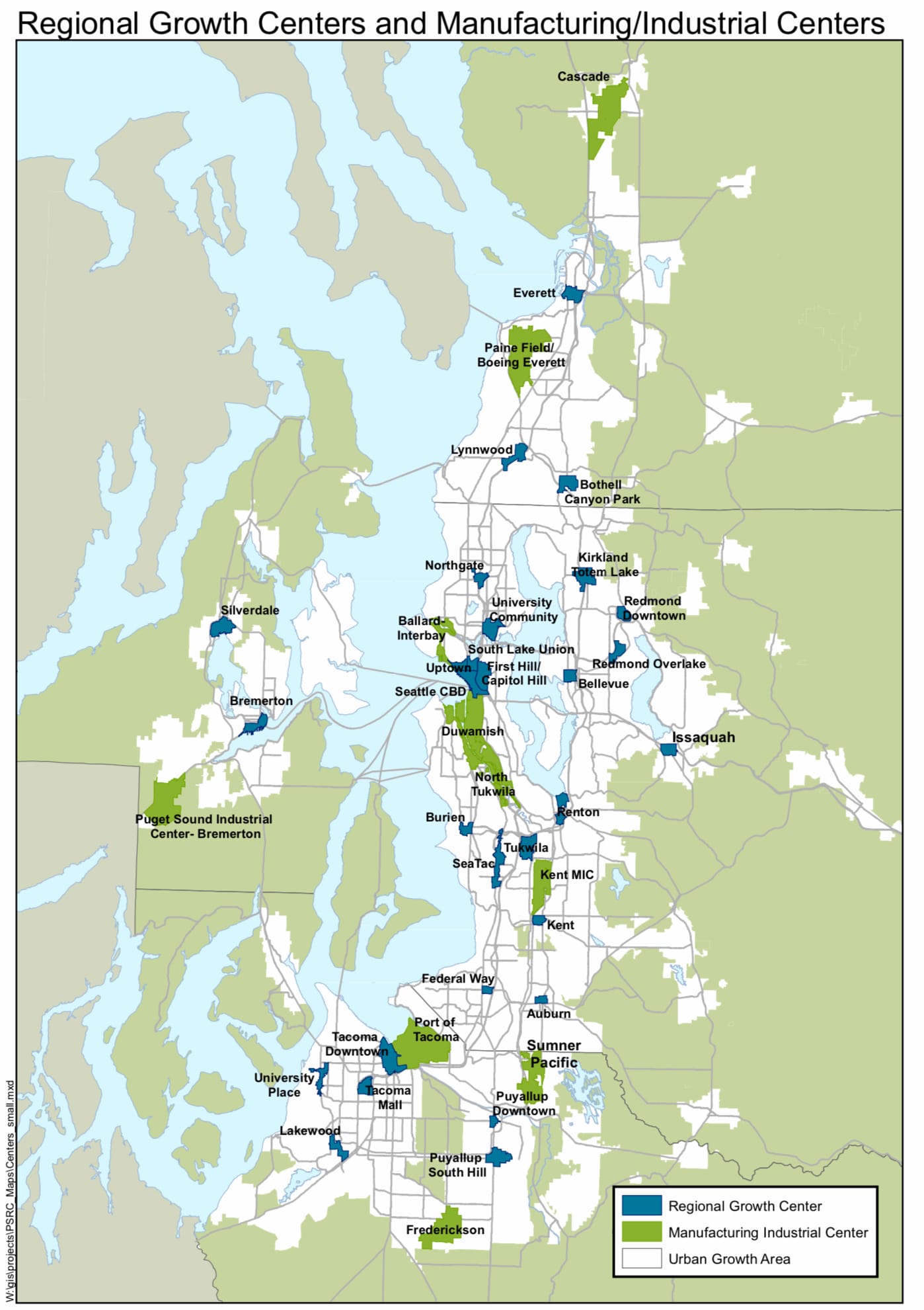

While the fight to create new budgets and programs and homes in Seattle was underway downtown, a little observed and often forgotten group of elected officials met to talk about housing on a regional level. Both of these talks grappled with the effects of development, displacement, and economic opportunity. But where City Hall was the site of grassroots organizing, the regional Growth Management Policy Board of the Puget Sound Regional Council was the site of bureaucratic sausage-making.

Contrasting with participatory budgeting, the Growth Management Policy Board (GMPB) meeting was an exercise in formalism. It is the unique brand of process that is disdained, but also readily used to crush those who do not follow it to the letter. As an extension of land use policy, it represents a crowning achievement in systemic racism expressed in membership, language, and topics.

Membership in the board is pulled from the elected councils and mayors of the counties and cities in the PSRC region. Out of 76 cities represented on PSRC, only seven are majority-minority: Tukwila, SeaTac, Fife, Renton, Kent, Federal Way, and Bellevue. Three tribes are represented: The Suquamish Tribe, Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, and Puyallup Tribe of Indians. Of the 33 voting members of the GMPB, four represent one of the Tribes or minority-majority jurisdictions. The two members of Seattle’s delegation to the GMPB, Dan Strauss and Andrew Lewis, did not attend the call.

The GMPB talks in the arch language of Planning, with a capital P. Based on prioritization and hierarchies, the Board directs the firehose of global real estate investment by allocating federal transportation money. Such a pressurized wave of money can make a small town explode in population or decimate an unprepared neighborhood. Avoiding that wave can protect enclaves of wealth and Whiteness.

GMPB heard a work plan to determine Regional Center typologies and prepare data for monitoring in 2025. The board is working with jurisdictions to review the criteria for Regional Growth Centers and Manufacturing Industrial Centers. Planning is based on jurisdictions applying designations to local circumstances. At their fall meeting, the board will hear more about certifying Center designations.

If it sounds like impenetrable gobbledygook, that’s because it is. It is a formal language of governance built to say very little in a lot of words. Nikkita Oliver recognized this in her introduction to the Community Teach-In. She opened the meeting “acknowledging that we have not all had access to power. We have not had access to institutions that control the processes that organize our society. We have not had access to the language of how to talk to those processes.”

While Decriminalize Seattle and King County Equity Now push for housing as a pillar of change in the justice system, groups like GMPB are actually deciding the location of housing throughout the region. The board heard presentations about work underway to update the Regional Housing Strategy. PSRC staff will deep dive into the region’s housing needs, look at gaps in actions and tools, and identify methods to move forward with implementation and monitoring. This information will be available to jurisdictions as they prepare to update their comprehensive plans in 2024.

Again, this does not get homes on the ground. It says where the road could go that will pave the way for surveyors to look at the locations that houses should not be built. It is the work happening at GMPB which corrals and undermines reform regardless of veto-proof majorities and participatory budgeting.

Individual members of GMPB did voice concerns about equity and the need for speed and bold vision in fixing the region’s housing deficit. But they did it in terms of large non-profits and countywide agencies. No one was talking about developing the small and informal network of groups that are effective in addressing housing issues because no one talking in the meeting is connected to that world.

And that’s the inadvertent ignorance allowed by our layered and piecemeal system of governance. Unlike Mayor Durkan, none of these boardmembers are actively throwing up obstructions and gaslighting (or gassing) activists. By virtue of convenient municipal boundaries, they simply get to not see. Instead they focus on a selected group of voices.

In a way, groups like the GMPB should understand the Trusted Messenger concept that activists like Sherae Lascelles are using to connect Black and Brown communities with resources and programs. Boards and elected officials get fed information by their network of staff and peer officials, and insulate themselves through formalism and jargon. Since it doesn’t appear they’re making a move in the other direction, we could outreach to them using trusted messengers that understand their peculiar language and customs.

In the meantime, communities are getting to work. Nikkita Oliver summed up the goals of the groups participating in the Community Teach-In. “So we want to be about building community power, about building our community muscle to talk about these issues, and building community ability to advocate for ourselves and solutions we know will serve.” Such vision and plans are novel in this region.