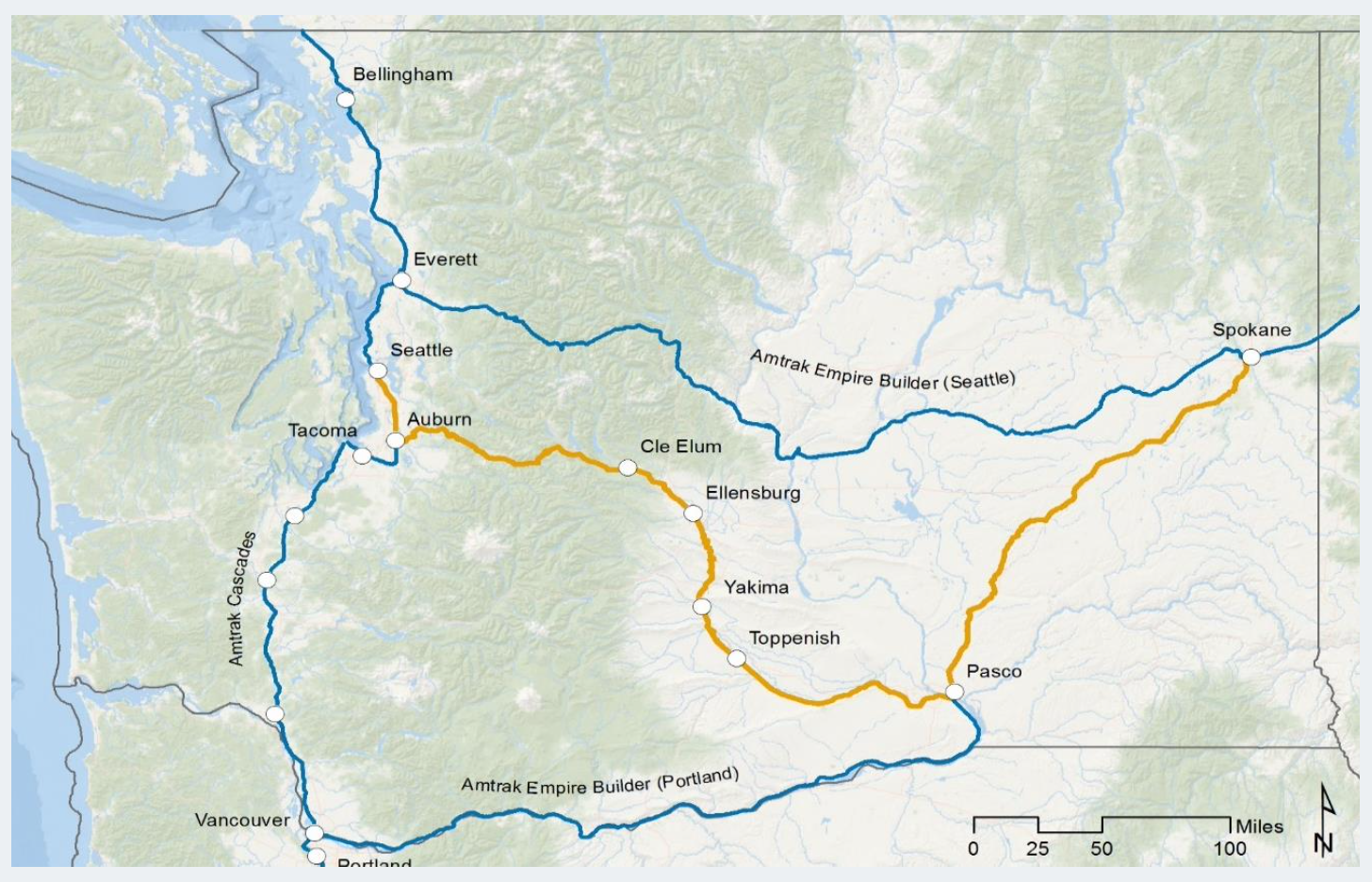

On Tuesday, the Washington State Joint Transportation Committee (WSJTC) and its consultants presented findings to state legislators on the east-west intercity passenger rail study. The study evaluates several corridor and service level options as well as ridership, costs, targeted corridor improvements, and operational models. Findings by consultants show that ridership between Seattle and Spokane could top 205,000 rides per year under the most robust scenario. That would include two daily roundtrips running through Stampede Pass, Yakima Valley, and the Tri-Cities area.

How we got here

The study is the result of a 2019 request by the Washington State Legislature. The body approved a proviso in the state transportation budget mandating that evaluation of a new east-west passenger rail corridor between Auburn and Spokane by this July, essentially a more robust update of the 2001 study. Five intermediary stops were included in the study proviso, but several extra stops were added by consultants to improve overall viability and provide rational system connections to existing passenger rail service. That is why Seattle and Tukwila found their way prominently into the study options.

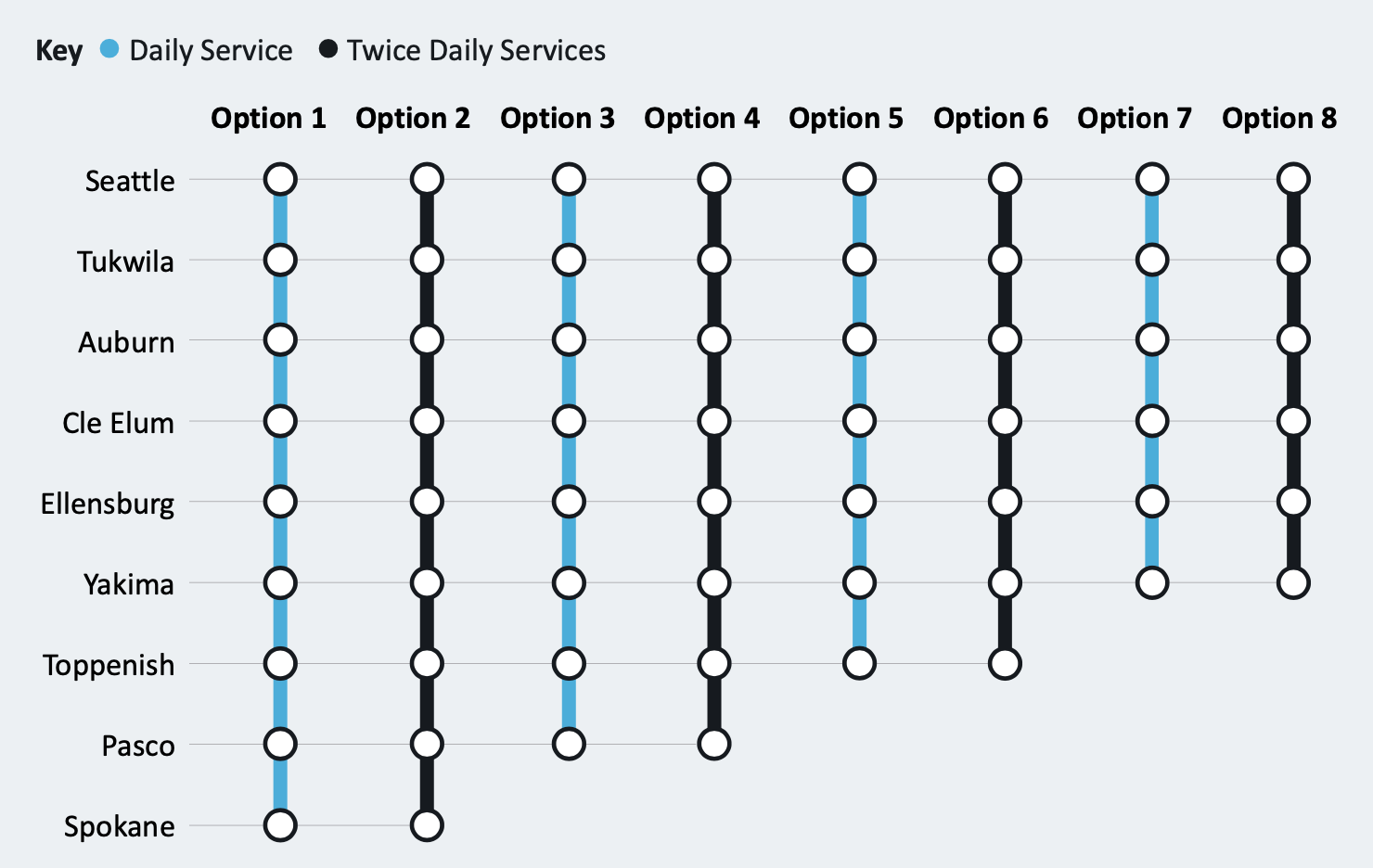

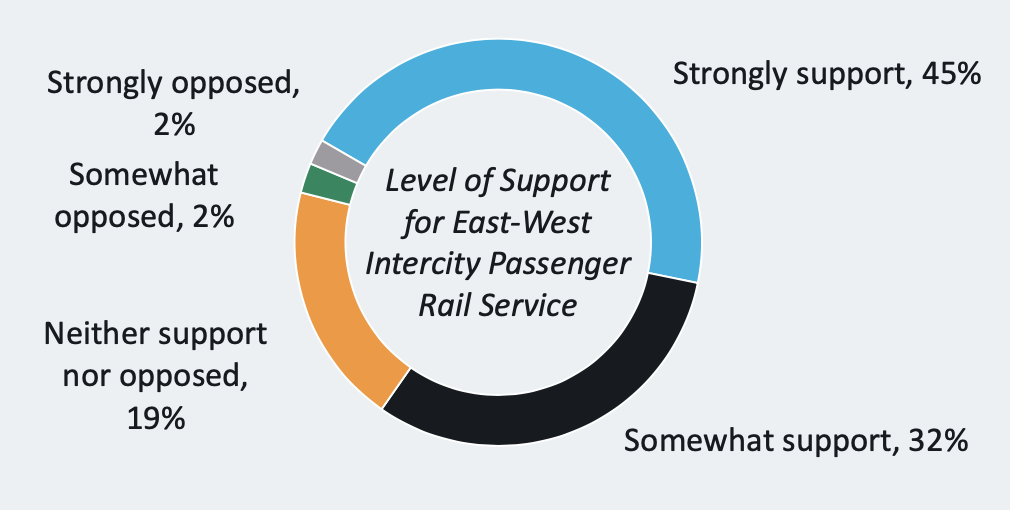

Overall support for additional east-west passenger rail service is very high. Steer, the study consultant, registered over 76% support from respondents; less than 5% of respondents indicated opposition to the idea. Underpinning the study are eight different service scenarios, which differ by the number of cities served by the line and number of daily roundtrips. The study limited the number of daily roundtrips to one and two scenarios. The shortest route scenario serves six cities running between Seattle and Yakima, and all scenarios would directly serve at least those six cities.

The consultants emphasized that the highest ridership projections are lower than Amtrak Cascades service, at about a quarter. But the comparison is a little misleading given that Cascades operates along a longer, denser corridor with three variations and four or eight daily roundtrips, depending upon the counting method. The ridership and costs of operating the east-west service is in line with other state-sponsored intercity passenger rail services like the Amtrak Piedmont service in North Carolina.

Key findings of the eight service options

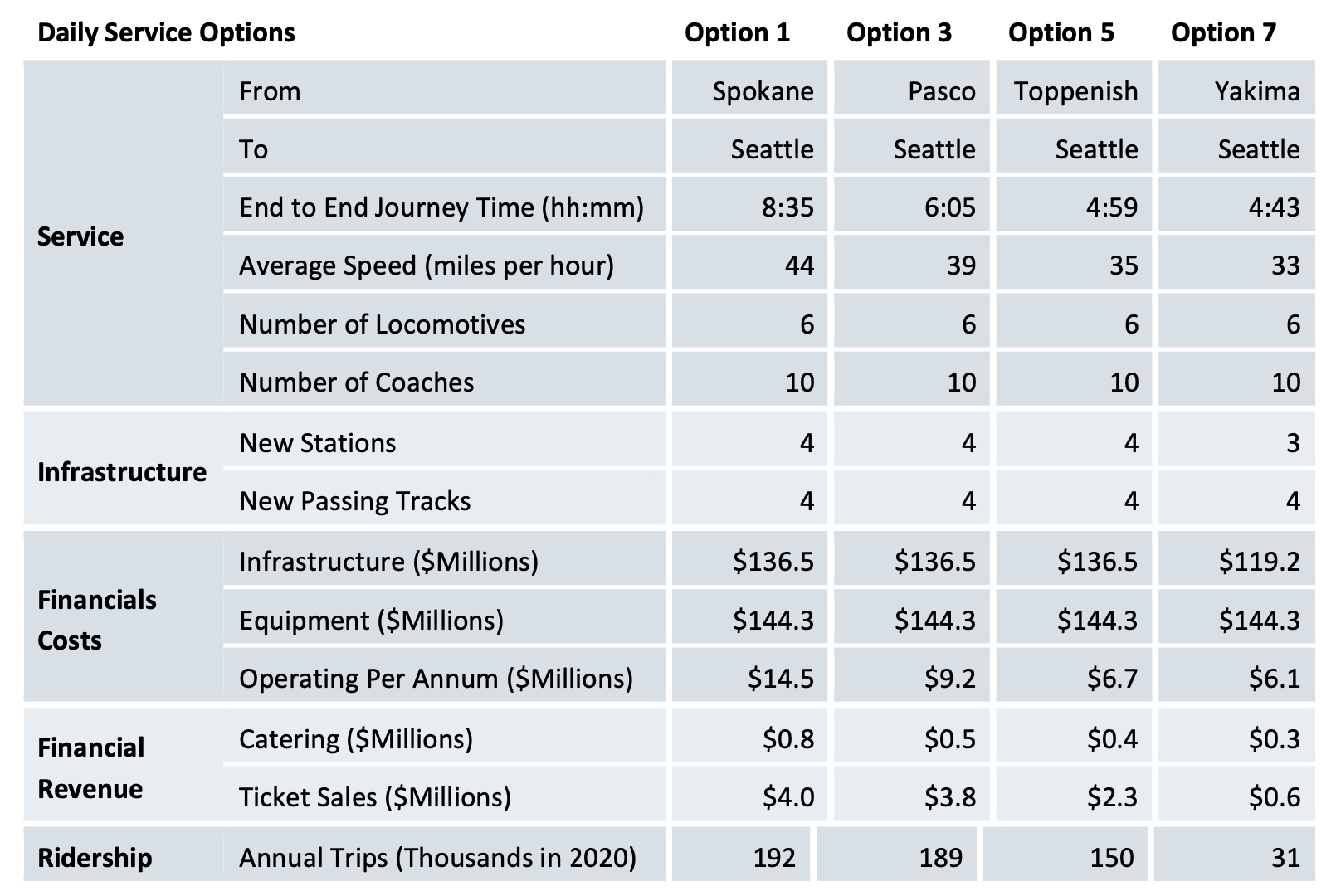

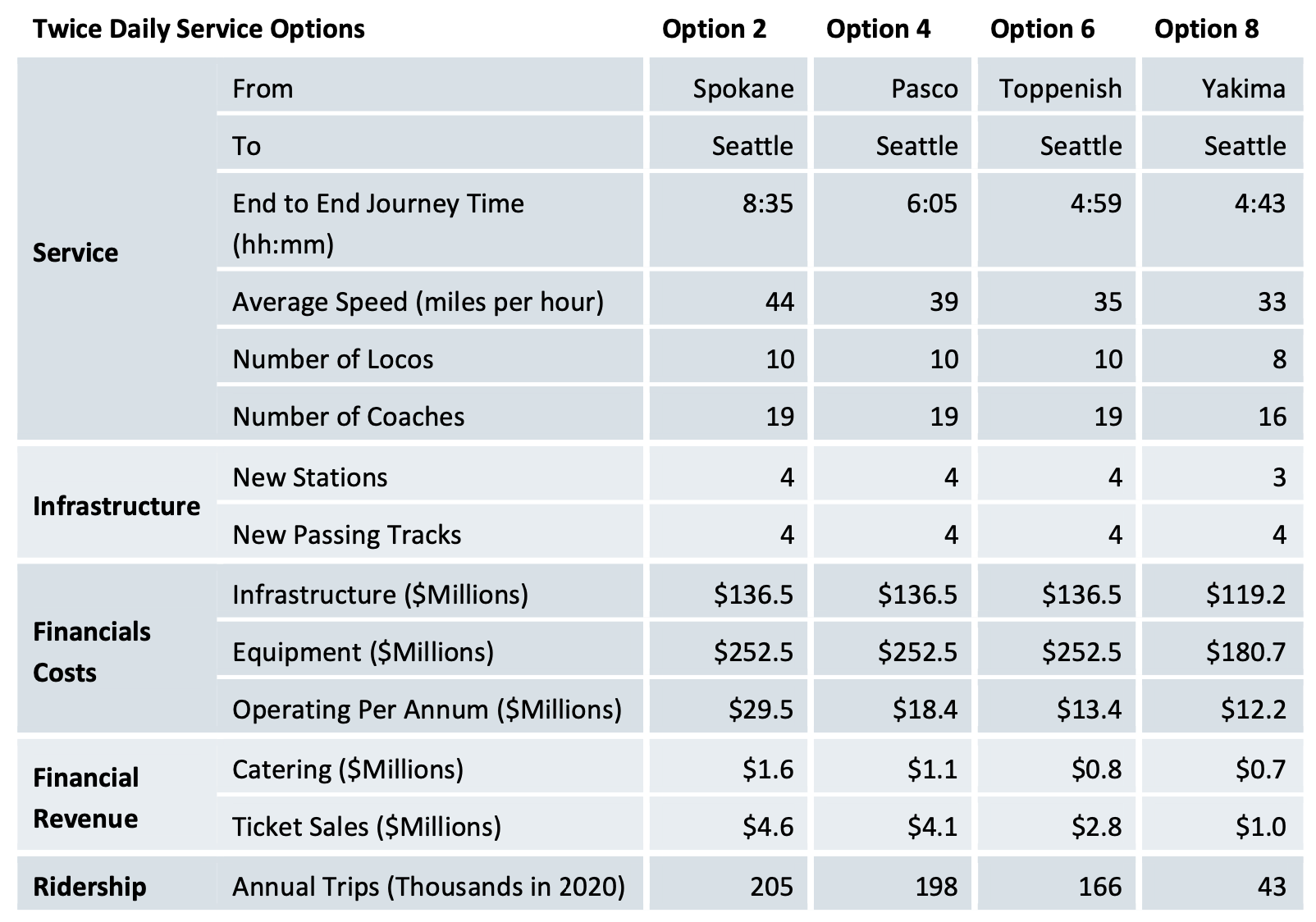

Initial startup costs for the service generally range from $263.5 million to $388 million, which would go toward purchasing rolling stock, infrastructure improvements, and station construction. The study considers the four- and eight-coach trainsets and would likely require two locomotives per trainset since the Stampede Pass incline is so steep and challenging. Up to four trainsets could be required for the corridor, including spares in case equipment needs to be taken offline for maintenance and repair.

The consultants provided a high-level breakdown of the key startup costs, including:

- $64 million to $75 million for new passing and siding tracks;

- $50 million for four-coach stations and $120 million for eight-coach stations (though the costs could be higher for better quality stations); and

- $144 million to $252 million for rolling stock equipment.

On the low end, Options 7 and 9 would run service between Seattle and Yakima, taking about four and a half hours. These options would generate very low ridership in the range of 31,000 to 43,000 riders per year. Farebox recovery, which is inclusive of food sales, would be fairly low at about 15% to 14%, respectively among the options.

On the high end, Options 1 and 2 would run service between Seattle and Spokane. The travel time for the service would be approximately eight and a half hours end to end. Annual ridership would range from 192,000 to 205,000 with a modest farebox recovery of 33% to 21%, respectively.

Option 3 would net the highest farebox recovery rate at 47%, but would be only one daily roundtrip between Seattle and Pasco. Ridership is still projected to be healthy though with 189,000 annual rides. Travel time for the service is assumed to be about six hours.

During the presentation, the consultants noted that the real ridership maker for the corridor is the central portion, specifically in the Yakima Valley. Including Yakima and Toppenish in the model showed that ridership would be significantly boosted with trips running between those two cities and cities in Kittitas County, representing nearly half of all ridership. The consultants noted that this was strongly indicative of pent up demand in the corridor for a high quality transit service.

Competitiveness, connections, and constraints

On the competitiveness front, the train would generally be slower than many other options–at least under perfect conditions on paper–from Seattle to Pasco–and other destinations in between. But the reliability of driving, flying, or taking the bus suffers during certain times of the day and year.

| Destination from Seattle | Train | Bus | Plane | Car |

| Cle Elum | 3.00 hours | – | – | 1.25 hours |

| Ellensburg | 3.50 hours | 2.50 hours | – | 1.75 hours |

| Yakima | 4.25 hours | 3.00 hours | 2.50 hours | 2.25 hours |

| Toppenish | 5.00 hours | 5.25 hours | 3.00 hours | 2.50 hours |

| Pasco | 6.00 hours | 5.00 hours | 3.00 hours | 3.50 hours |

It is not uncommon for Snoqualmie Pass–the main all-year thoroughfare between the two sides of the Cascade Mountains–to close for hours during the winter or be clogged with general recreational congestion on summer weekends. Congestion in the Seattle area is also quite awful on a nearly daily basis. And regional airline service is notoriously unreliable, expensive, and requires substantial time traveling to the airport to check in and collect baggage. So the train may win out on reliability and cost for many travelers, but the ridership analysis likely underweights this consideration significantly in the western corridor.

The east-west rail line could be well positioned to connect with other major rail services in five cities along the corridor. Virtually all cities have other connecting transit options, such as local, regional, and intercity bus services. It bears mentioning, however, that Empire Builder service can wind up arriving in Spokane and Pasco in the middle of the night, making it a less than convenient option. Relatedly, state legislators asked if Steer looked into additional Seattle-Spokane service via Stevens Pass since existing Empire Builder service is not terribly ideal, to which consultants essentially said “no” because of the limited mandated study parameters.

| Connecting Rail Service | Seattle | Tukwila | Auburn | Pasco | Spokane |

| Amtrak Cascades* | X | X | – | – | – |

| Amtrak Empire Builder** | X | – | – | X | X |

| Amtrak Coast Starlight** | X | – | – | – | – |

| Sound Transit Sounder North*** | X | – | – | – | – |

| Sound Transit Sounder South*** | X | – | X | ||

| Sound Transit Link**** | X | – | – | – | – |

Table Notes: * intercity regional passenger rail, ** long-distance passenger rail, *** commuter passenger rail, and **** regional light rail.

The stretch between Auburn and Cle Elum is particularly sluggish as tracks wind their way through the suburbs, foothills, and Cascades. Travel time between the two stops is estimated to be just under three hours (approximately two hours and 56 minutes) according to the sample schedules. Many of the curves and sections have very low speed restrictions, which would reduce the average speed to 26 mph even with higher speeds allowed for passenger trains.

The study does identify sections of the corridor between the two stops that could benefit from straightening tight curves, siding tracks (increasing tracks to two), and snow protection improvements. The costs of these improvements would not come cheaply, but they could help shave off quite a bit of time.

Speeds above the typical limit of 79 mph were not analyzed in the study, but if special approval is granted on higher rated sections of the corridor east of Cle Elum, then travel times could be further reduced. Passive tilting technology, high-level platforms for boarding, automatic doors, and no checked baggage for intermediate stops could also help reduce general travel times.

The study suggested if the full suite of track, equipment, and operational improvements are used, travel times could be reduced by an hour between Seattle and Spokane. However, the increased ridership was marginal, rising slightly from 205,000 to 215,000 on the high end. Perhaps the time savings were not drastic enough, but generally ridership modeling is sensitive to travel times and reliability–though Greyhound advertising the bus trip from Seattle to Spokane at five and a half hours (using the more direct I-90 route) is likely a factor, too.

Operational models

The consultants highlighted three operational models in the study for the state to consider, which include options for a public operator concession, private operator concession, or a statutory state operator. Each of these models have their pros and cons, but the public operator concession is the option most familiar to the state. This would essentially be identical to the Cascades service sponsored by the state and operated and maintained by Amtrak. Assets such as rolling stock, stations, tracks, and facilities would be directly owned by the state, except where leased from Amtrak or private railroads.

The private operator concession would be open to any other third-party railroad company. Notable examples in the American market include Keolis, Herzog, Deutsche Bahn, and RATP. Virgin Trains USA, which operates the Brightline service in Florida and is pursuing high-speed rail between Los Angeles and Las Vegas, might also be interested in something like this. This model could deliver substantial operational cost savings and even enhanced rider experience over Amtrak. There are also possible equipment procurement advantages with the model.

The main downside the private operator concession is the negotiation disadvantage it presents in acquiring slots on Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s tracks, which could essentially wipeout cost savings. Going to this model would best be served if the Cascades service was also folded under the same operator. Not mentioned in the presentation by Steer’s project manager is the seamless ticketing and reservation system that sticking with Amtrak presents, which may be useful to many riders.

The third model with a statutory state operator would be fairly unique for such a long regional intercity passenger rail line, but it could be done. Initial startup cost would be significant to establish the entity and build institutional know-how, but there are upsides in streamlining the process of designing, building, and operating the line. Doing this would most be prudent if also integrating the Cascades service in order to benefit from economies of scale and shared human capital.

Missed opportunities and future

The study does miss out on some opportunities to possibly improve ridership along the corridor and may be worth a closer look down the road. In the Yakima Valley, there is Prosser which represents a notable population center rivaling Toppenish and could provide a good catchment for local ridership. Between Pasco and Spokane, intermediate stops at Connell, Ritzville, and Cheney also offer additional ridership opportunities and destinations. And then west of the Cascade Mountains, stops in Covington or Maple Valley could prove useful to capturing more of the urban Puget Sound population.

Of course, each stop that is added does introduce more dwell time and reliability risk to a schedule. Those tradeoffs might be warranted though if there are consequential ridership and cost recovery increases. On top that, these stops could justify higher levels of investments and alternative schedules with more than two daily roundtrips.

Ultimately, this study puts the state in a good position to chart the next steps in planning and executing a new east-west passenger rail line. But will the governor and state legislators move to act? Or will this study just end up on the shelf among the heaps of other state transit studies? Time will tell.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.