For over half a century, America’s housing policy has been shaped around a deeply regressive tax deduction. That has to change.

Imagine yourself standing in front of a stereotypical single-family home. There’s a mature maple tree in front yard, a driveway with a basketball hoop, and a deck out back with a charcoal grill. Now picture yourself standing in front of a fifteen-story brick public housing development that occupies half a city block. There’s also a basketball hoop set up in a small parking lot. A narrow strip of grass lines the sidewalk leading to an alley.

Which of those residences do you associate with government spending and support? Which of those residences stirs up pejorative descriptors like “welfare queen?”

For decades, Americans have been taught that the single-family home represents self-sufficiency, hard work, and economic success, while the public housing development represents laziness, graft, and bloated government. But societal perceptions conceal a significant truth.

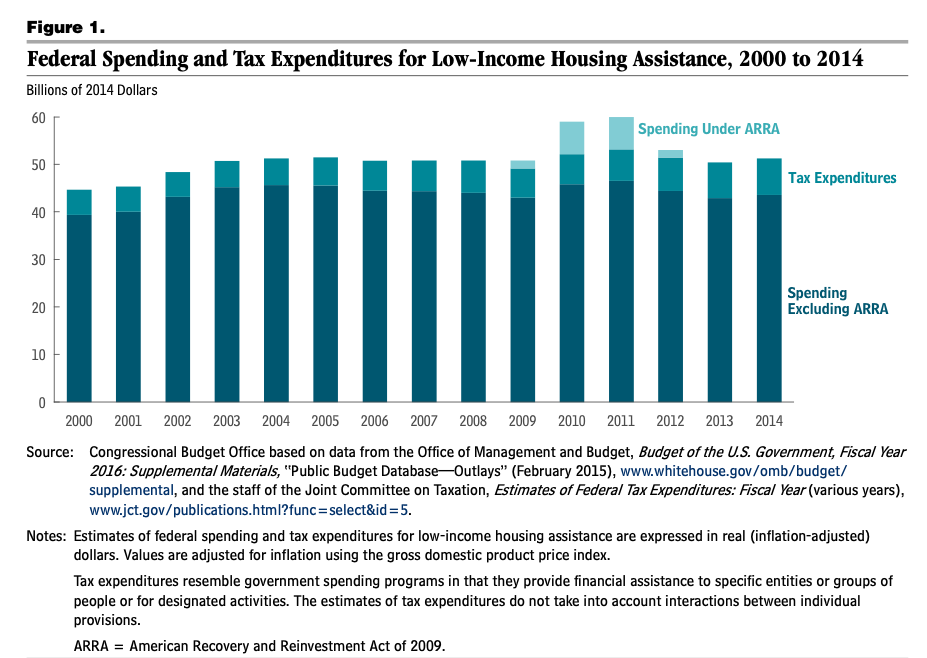

Homeowners don’t usually think of themselves as recipients of government largesse. Yet for decades, the American government has spent billions of dollars more supporting homeownership through tax deductions like the Mortgage Interest Deduction (MID) than it has invested in affordable housing. The effects of these policies have been harmful on many levels, but they have been particularly disastrous for black Americans who have historically faced barriers to homeownership.

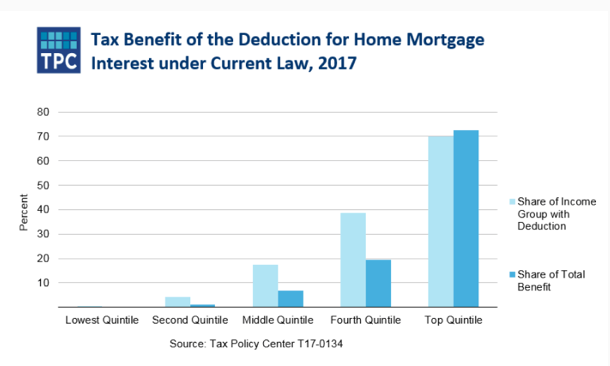

In a 2015 New York Times article, “How Homeownership Became the Engine of American Inequality,” Matthew Desmond wrote, “America’s national housing policy gives affluent homeowners large benefits; middle-class homeowners smaller benefits; and most renters, who are disproportionately poor, nothing.”

Desmond continues, “It is difficult to think of another social policy that more successfully multiplies America’s inequality in a such a sweeping fashion.”

Those strong words are backed up by statistics.

[In 2015] the federal government dedicated nearly $134 billion to homeowner subsidies. The MID accounted for the biggest chunk of the total, $71 billion, with real estate tax deductions, capital gains exclusions and other expenditures accounting for the rest. That number, $134 billion, was larger than the entire budgets of the Departments of Education, Justice and Energy combined for that year.

Matthew Desmond, “How Homeownership Became the Engine of American Inequality,” The New York Times.

Bundled into that $134 billion was investment in the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program (LIHTC), which finances the construction, rehabilitation, and preservation of housing affordable to lower income households. Historically, the federal government has spent around $7 billion annually on LIHTC, a fraction of what it has spent on homeowner subsidies.

Factoring in all affordable housing investments (e.g., housing choice vouchers and public housing) made by the federal government, you will still find that the amount spent on the MID alone has exceeded all affordable housing investments by about $20 billion annually.

Because the tax deductions homeowners receive from the MID increase with the size of their mortgage, borrowers with high incomes with large mortgages receive the most financial support. In 2018, about 63% of the MID benefit was paid out to the 8% of American households earning $200,000 or more annually.

So what exactly is MID?

Economists have long loathed the MID; some have gone as far to say that the tax policy should have never existed. To understand why the MID is so hated, let’s take a moment to understand better how it works.

The MID is an income tax deduction that can be taken on interest paid on up to $750,000 of mortgage debt for married couples, $375,000 for single filers. The tax deduction applies to both primary and secondary residences. So, if you and your spouse owe $500,000 in mortgage debt on your townhouse in Seattle and $250,000 in mortgage debt on your vacation ski cabin in the foothills of the Cascades, you can deduct the interest you pay on those mortgages from your federal income taxes to the tune of thousands of dollar a year.

Until recently, the cap was $1 million for married couples. However, under the Trump administration’s 2016 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the amount was reduced to the current $750,000 limit, a reduction that’s set to expire in 2025.

It’s easy to fault the MID for being regressive and disproportionately favoring white Americans, about three quarters of whom are homeowners. But the damage does not stop there. According to an article by St. Louis Federal Reserve lead economist Bill Emmons, the MID also:

- Encourages the construction of bigger more expensive homes, contributing to urban sprawl.

- Drives up housing prices, making homeownership less attainable for low- and middle-income earners because tax benefits like the MID are “capitalized” into house prices, pushing them higher than they otherwise would be.

- Increases the likelihood of mortgage defaults during economic downturns by enabling people to finance their homes with larger debts.

If the federal government were to eliminate the MID, Emmons argues that the United States would see a 5% increase in the homeownership rate and roughly a 4% decline in average house prices, with larger price declines for more expensive houses.

A previously untouchable “public good” comes under new scrutiny

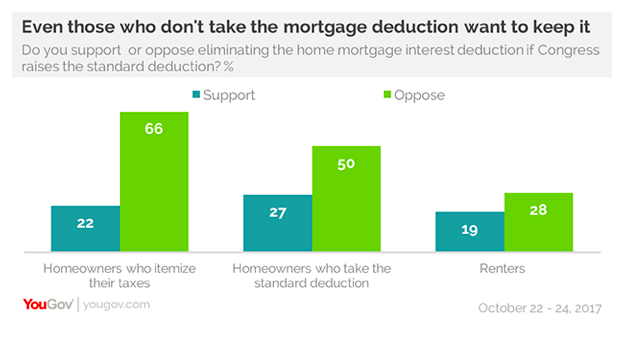

Until recently, Democratic and Republican political leaders alike have largely considered MID to be sacrosanct. For one thing, the policy is popular with many Americans, even those who do not benefit from it. A 2017 poll found more homeowners and renters who do not benefit from the deduction supported maintaining it than eliminating it.

There are many explanations for this baffling statistic, but extensive lobbying from real estate and home building industries portraying the MID as a crucial form of support for middle class homeowners has controlled the narrative around the MID for decades, distorting people’s perceptions of the facts around the policy, and making it difficult for politicians to oppose it.

In 2016, as part of the discussion around the Trump administration’s proposed changes to the tax system, the first serious conversations around the the reform or elimination of the MID occurred. While elimination was quickly taken off the table, the first reform of the policy did occur, a decrease of eligible mortgage interest cap from $1 million to $750,000. Republicans actually initially proposed a $500,000 cap; however, Democratic leadership negotiated the increase to its present level out of a concern of a backlash from affluent constituents in expensive coastal cities who might resent their tax deduction getting cut in half.

But deeply ingrained social perceptions surrounding the MID as a largely middle-class benefit has misguided other politicians as well. In a blog post promoting their work to lobby against the elimination of the MID, Seattle-King County Realtors recounted their visits to the offices of Congressional Representatives Suzan DelBene (D), Pramila Jayapal (D), and Senator Patty Murray (D), describing the words of support they received from both Rep. DelBene and Sen. Murray’s offices. “It is ironic that we are going after deductions that help grow our communities,” concluded one of DelBene’s staff members.

For progressives, there is little to like about the Trump administration’s changes to federal tax policy, which has slashed corporate taxes, ballooning the federal deficit. However, placing the new $750,000 cap on the MID and raising the Standard Deduction to $24,000, actually accomplished something positive. The move has made the MID even more regressive as to who it pays it benefits out to than it was previously, rendering it more difficult for liberal and moderate lawmakers to defend their support.

This might be the moment when America can take steps meaningfully reform its housing policy so that it finally prioritizes the kind of support it has always purported to provide to low- and middle-income Americans, but has overwhelming failed to do.

The stakes around such a change are high. Even with the $750,000 cap, the Brookings Institution estimates that the MID will cost the federal government about $900 billion in revenue over the next decade, a nearly trillion dollar tax subsidy for the wealthiest Americans.

That trillion dollars could be invested in creating more social housing and adequately funding existing housing choice voucher programs like Section 8 so that eligible families don’t have to languish for years on waiting lists, hoping for an opening that may never arrive. The funds could be invested in truly growing our communities, especially in programs and services that prioritize the needs of black Americans, who faced with racism and exclusionary housing practices, have been left behind in economic booms and dealt heavy blows in times of recession.

Part Two of this series will focus on how the Mortgage Interest Deduction has entrenched the racial wealth gap in the United States.

Do you have a minute to take action against the MID? Contact your local Congressional Representative and Washington State Senators. Find your Congressional Representative here. Contact Senators Maria Cantwell and Patty Murray online.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.