The double-whammy of a global pandemic and parallel recession has taken a toll on Sound Transit finances. Agency staff have warned that a sustained and deep recession seems inevitable, following a similar course of the Great Recession of 2007-2009, that could impact capital investments in light rail, commuter rail, and bus rapid transit expansions.

Financial forecasts for a severe economic downturn paint a picture of long-term losses totaling $12 billion through 2041, and a less severe forecast assumes a program deficit of $7.8 billion over the same timeframe. As a result, the agency is coordinating a program realignment process that may result in adjustments to projects and financing, just in case a significant recession is a real and lasting thing.

The capital expansion program was always fragile with little financial cushion in the next decade–particularly if hoping to avoid significant delay to the timleine. The primary challenge for Sound Transit is limitations on the statutory debt limit. As approved, the transit agency can only issue debt up to 1.5% of the total assessed property value within the taxing district. That limit changes year to year as property values rise and fall. And based upon the current trends, that limit could be quickly reached–as soon as 2028–if the levers on revenues and expenditures are not modified.

In the fall, Sound Transit had assumed that the debt limit would never be exhausted during capital program plan through 2041–the time period for completion of voter-approved Sound Transit 3 projects.

Sound Transit does not rely exclusively on debt (e.g., bonds and loans), of course, to directly fund project expenditures. There is a mix of revenue sources that make up program financing, such as the motor vehicle excise tax, property taxes, sales taxes, rental car taxes, federal grants, and fares. The bulk of revenue is the sales tax, which is supposed to account for as much as 53% of all revenue.

Unfortunately, the pandemic quickly derailed economic activity in March. Recent data shows that many revenue sources have shrunk precipitously. Agency staff reported on Wednesday that March sales tax collection was down 25% from the year prior. In April, motor vehicle excise tax collections had collapsed by a comparable amount and the rental car tax dove off the cliff, dropping 87%.

Using the moderate and severe scenarios, Sound Transit is modeling a brutal few years ahead:

| Moderate Recession Scenario | 2020-2021 |

| Sales Tax | -$766.2 million |

| All Tax and Fare Revenues | -$908.9 million |

| Net Loss After CARES Act | -$742.9 million |

| Severe Recession Scenario | 2020-2021 |

| Sales Tax | -$976.0 million |

| All Tax and Fare Revenues | -$1,118.6 million |

| Net Loss After CARES Act | -$952.6 million |

Even with emergency CARES Act funding coming through, the financial toll of declining taxes is serious. With projects in the pipeline and maintained operations, Sound Transit will increasingly need to issue debt to keep the overall program moving forward. This is kind of like taking out loans to cover rent payments while one’s daily income from work shrinks due to fewer scheduled hours.

Agency staff have cautioned officials that they should not be too hopeful an economic bounce-back is likely. They fear that impacts to sales tax collection will be a long-term hit with Sound Transit not recouping the difference between the pre-economic downturn financial plan and economic downturn damage. Pointing to the Sound Transit 2 (ST2) program, agency staff showed that the Great Recession blew a big hole into revenues that were never recovered during the boom times of the 2010s. By 2019, Sound Transit still had collected 24% less in taxes than the ST2 plan had assumed.

Fortunately, Sound Transit has been fairly conservative in assuming lower federal assistance and higher project costs in many cases, and there are tools that Sound Transit could use to keep things on track or at least closer to track, but the board of directors will be responsible for deciding which tools to deploy to salvage what looks to be a battered capital expansion program. One of those tools is increasing the debt capacity.

Officials could purse a higher debt capacity if voters approve greater bonding authority. Sound Transit has a legal right to seek an increase of the debt capacity to 5% of the assessed property value of in the tax district. This would require a special ballot measure with at least 60% of voters approving it. Sound Transit 3 passed with 54% in 2016, so it is plausible that voters may be willing to sign off on the change, patching the hole and essentially wiping away any program concerns. The debt could be paid off in later years through tax receipts and grants from state and federal governments.

Another tool that Sound Transit has is direct taxation. Not all of the transit agency’s taxing authority has been exhausted. As an example, the rental car tax could be further increased. Lobbying the state legislature for new taxing authority could be on the table, too. One choice could be authority to collect impact fees on new development. Some members on the board of directors seemed amenable to pursuing new taxing measures.

Sound Transit does not necessarily have to cut or delay whole projects to address financial impacts. In this area, there are several tools to contain costs. A prominent one is using federal loans under the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program. The transit agency has successfully used this program in the past to greatly reduce borrowing costs with lowered interest payments. Likewise, Sound Transit could seek other borrowing tools that keep costs down.

Operations is a heavily fraught area, but keeping labor costs down and higher farebox recovery could reduce long-term financial constraints. Agency staff also mentioned trimming project scopes and other programs that may not be priorities. Some planned projects, for instance, are more focused on delivering parking than transit or include purely aesthetic components that do not improve system operations or the rider experience over more affordable options.

The other big tool that officials could use is project timelines. As a blunt mechanism, Sound Transit could simply slow project delivery by increasing project construction timelines, breaking projects into phases, or wholesale delaying of the capital program. Agency staff said with very high confidence that an across-the-board program delay of five years would resolve any financing constraints. This would push full program delivery past 2041, however.

The capital program plan envisions completion of an early big-ticket item in 2025 with Stride bus rapid transit on I-405 and SR-522/NE 145th St, and then winding down in 2041 with the South Kirkland-Issaquah Link light rail project. The timelines are not inevitable though.

Many of the biggest projects will not be approved for a “project to build” until 2021 or 2022. At that point, officials can set the scope of what a project consists of, including station amenities, alignment profiles, and station locations. It does not commit the transit agency to a specific project budget or spending timeframe. That comes later through the “baselining” process, which allows for bid advertising, spending commitments, and defined project timelines. Selecting a project to build, however, does allow Sound Transit to become eligible for further project design, permitting, and grants.

In a typical program from cradle to grave, a project might take 10 years to complete. Much of the project costs, as much as 70%, are backloaded in the construction period, which is relatively short. More often than not, the bulk of the project timeline is dedicated to environmental review and pre-engineering as well as permitting, final design, and right-of-way acquisition. Initial costs critical for making a project eligible for federal grants is very affordable, accounting for 10% or less of total project cost.

Agency staff suggested that if projects were to be spread out over time, board members should not fret at keeping environmental review and pre-planning work from moving forward. Even if local revenue remains constrained, making a project eligible for federal funding could wind up being a boon. Congressional Democrats just issued a transportation funding package, dubbed INVEST in America Act, that would boost capital grants for transit by leaps and bounds over the austerity-first and unserious Trump administration, so there is good wisdom in keeping things moving. Getting a project through the environmental and pre-planning process also means that a project could be kept alive by making actions to realize the larger project, such as purchasing right-of-way and beginning design, even though financing for major construction may need to be slowed or punted.

Similar to 2010, Sound Transit has begun an engagement process with board of directors members to determine if and how the Sound Transit 3 program should be realigned. Agency staff outlined some realignment criteria that could be used in review of projects, particularly as it relates to priority for delivery. Two suggested criteria were described as “pass/fail” screens for priority:

- “System affordability: Is the full program affordable at the system level?”

- “Subarea affordability: Is the full program affordable at the subarea level?”

Either a project is affordable or it is not systemwide and within a subarea (there are five subareas in the taxing district). Unfortunately, the affordability metric could put Ballard Link in the crosshairs since it is the most expensive, particularly since its sticker price typically includes all of the cost of a second transit tunnel through Downtown Seattle even though it benefits the entire system by expanding overall capacity.

Another set of suggested criteria dig deeper into other dimensions of core Sound Transit 3 principles. These include:

- “Completing the spine: Does the project advance the regional HCT spine?”

- “Connecting centers: Does the project connect designated regional centers?”

- “Ridership potential: How many daily riders is the project projected to serve?”

- “Socio-economic equity: How well does the project expand mobility for transit-dependent, low-income, and/or diverse populations?”

- “Advancing logically beyond the spine: Can the project be included financially once projects that advance the spine are included?”

Other criteria could be used and board members spoke about using a matrix that would screen projects. But the process will obviously be more complicated at projects could be spread out if the prevailing objective is slow project delivery.

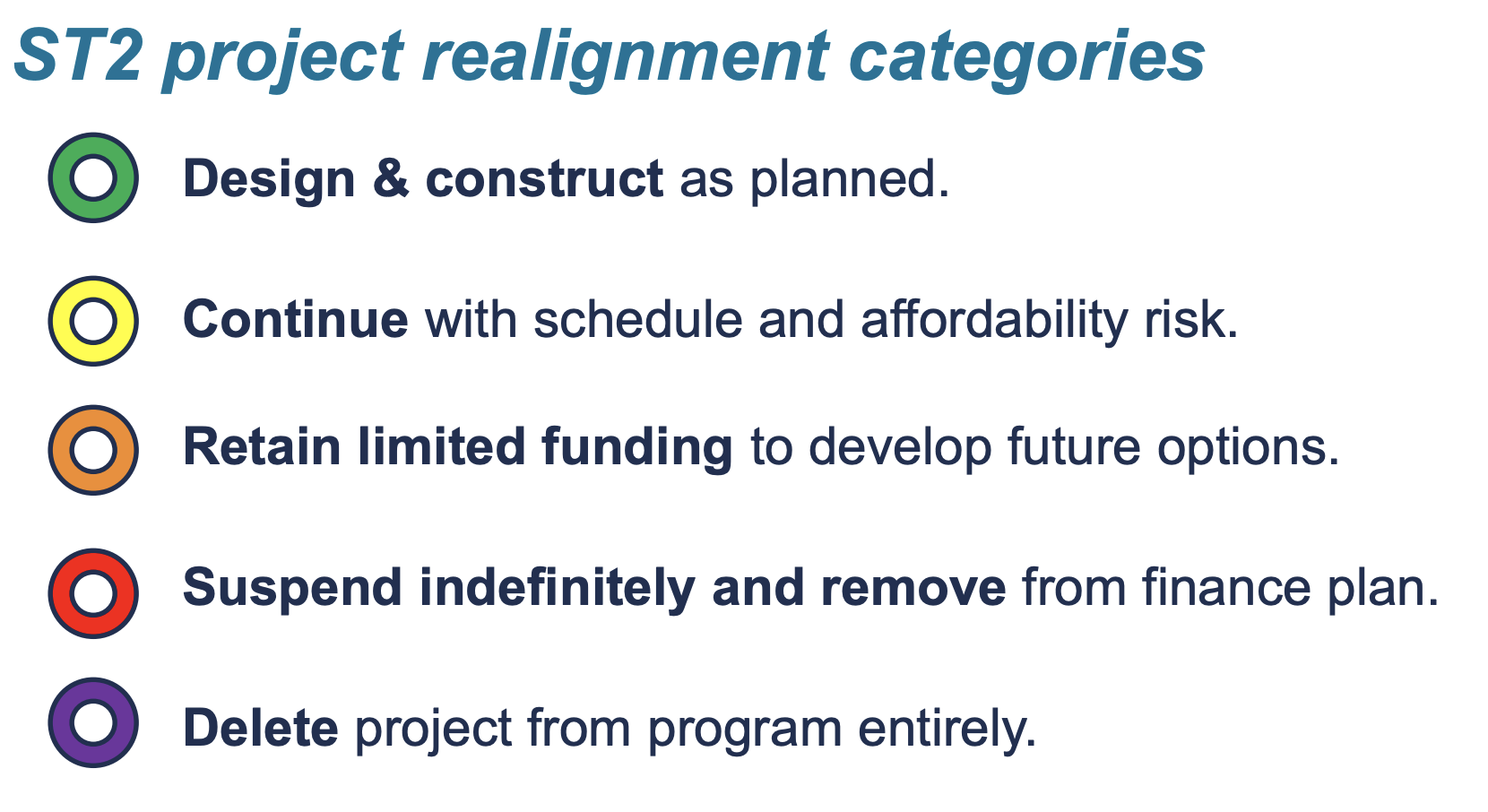

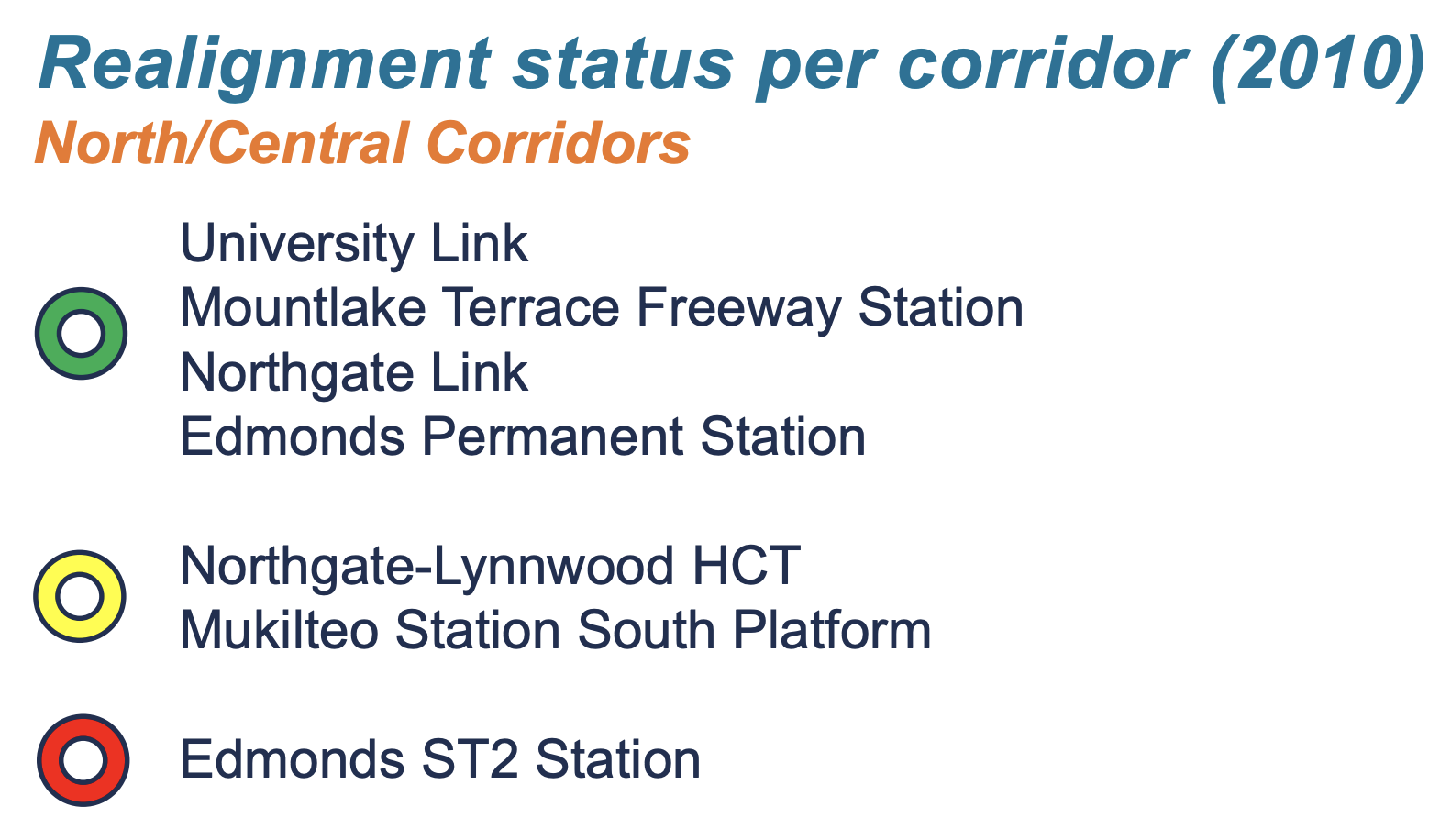

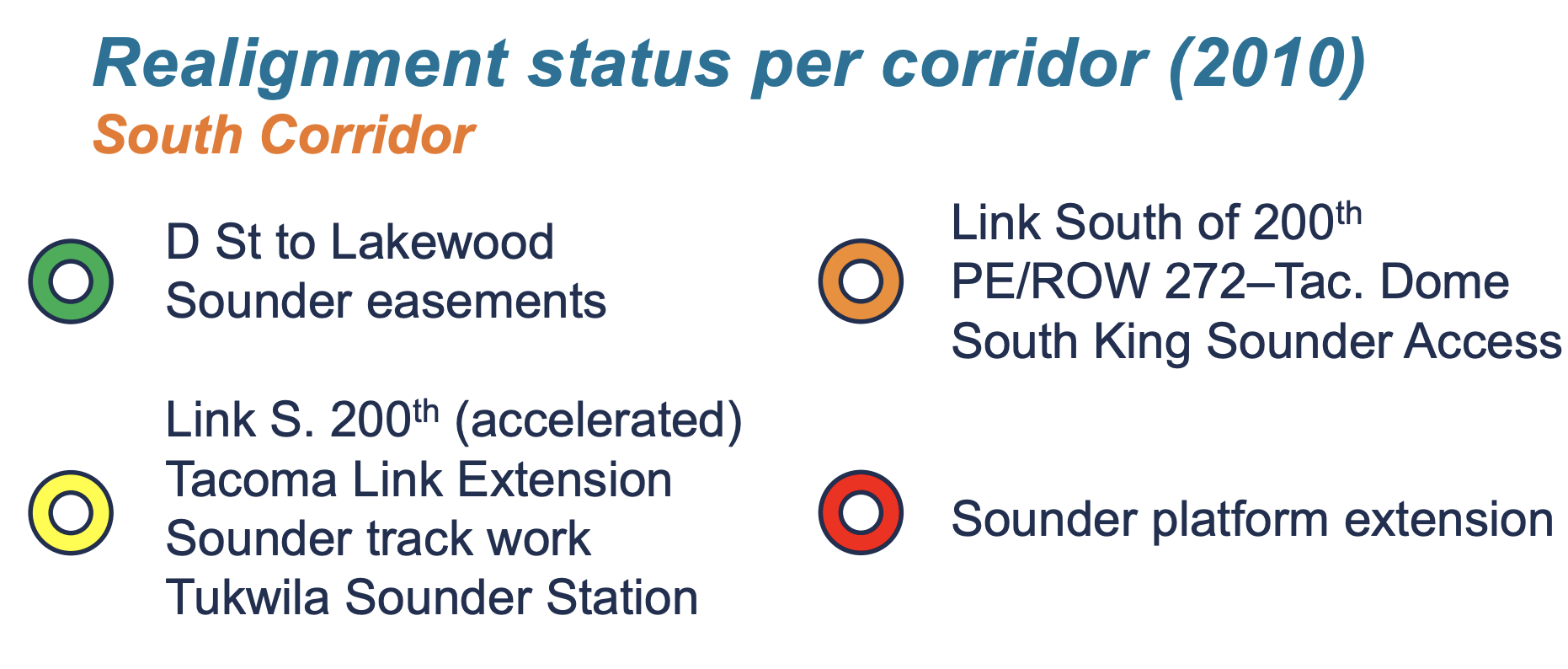

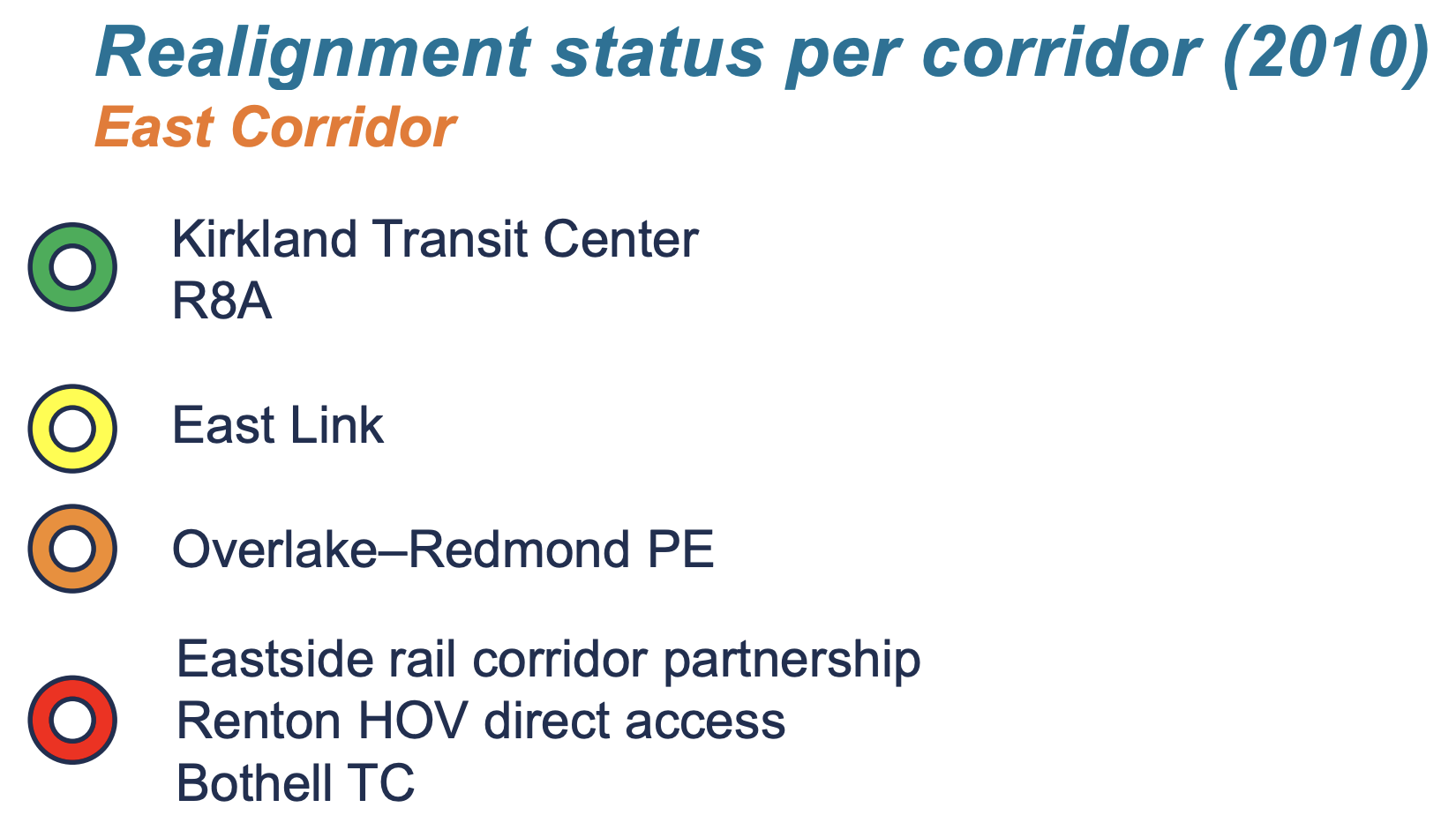

At a previous meeting, agency staff pointed back to the previous realignment process in 2010. The board of directors gave five rankings at that time for projects, ranging from proceed ahead with full speed ahead to deleting a project from the capital program. This came about by determining which projects were lower priorities in the system plan, where project scopes were yet to be fully defined, where ridership was anticipated to be lower, and what were generally considered to be discretionary programs.

In the North Corridor, University Link was greenlit to proceed for construction and completion by 2016 while a permanent Edmonds Sounder station was cancelled. Likewise, East Link was pegged for continued progress with some risk and the Redmond Link extension pre-planning was retained for the East Corridor.

Decisions like in ST2 will need to be made, but there are projects that are actively under construction that cannot be pulled back. Big ones like Northgate Link, East Link, and Federal Way are well on their way to completion with Northgate Link due to open in 2021.

The next project realignment meeting is planned for next week on Wednesday, June 11th. The Executive Committee will focus on the topic of realignment criteria. Then on June 25th, the Board of Directors will discuss scenarios and criteria. The process is expected to unfold across the summer, so where things end up is still uncharted.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.