Seattle can house 35,000 people on Jackson Park Golf Course by building on 60 acres of fairway and converting the remaining 100 forested acres to public park space.

By the year 2025, you will be able to take a 15-minute train ride from Downtown Seattle to a stop adjacent to 160 acres of publicly-owned land. There is no housing here, no shops, no roads, and the property is operating in the red. I’m talking about Jackson Park Municipal Golf Course. Golf participation isn’t just down in Seattle, it’s down nationwide. Whether it’s the time commitment, or the high cost it takes just to buy equipment, golf is bleeding participants and city money and Seattle has yet to come to grips with this reality.

The City of Seattle has begun to study what to do with excess publicly-owned property. Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda has brilliantly proposed leveraging surplus public properties for dense affordable housing. With the land already acquired, the city saves precious housing funds and gets to decide how it’s developed.

Seattle Must Leverage Its Assets

Golf participation on our municipal courses is in freefall, but Seattle’s population continues to rise. While we have a surplus in publicly-owned land, we have a shortage in housing. So, what if instead of hopping off the light rail and seeing a golf course, we enter a dense, vibrant walkable neighborhood free of car dependency?

Imagine living in a community where instead of the 15-minute neighborhood, you were in the five-minute neighborhood. You hop off the train, pick up some groceries, run to the bank, wave to your neighbors, see children at play, and walk into your home without ever needing to turn the ignition key. This isn’t just an unachievable utopia, it’s how people live in Barcelona, in Paris, in Rome, in Tokyo, and in New York City. Increasingly it’s how people live in some of the most walkable parts of Seattle.

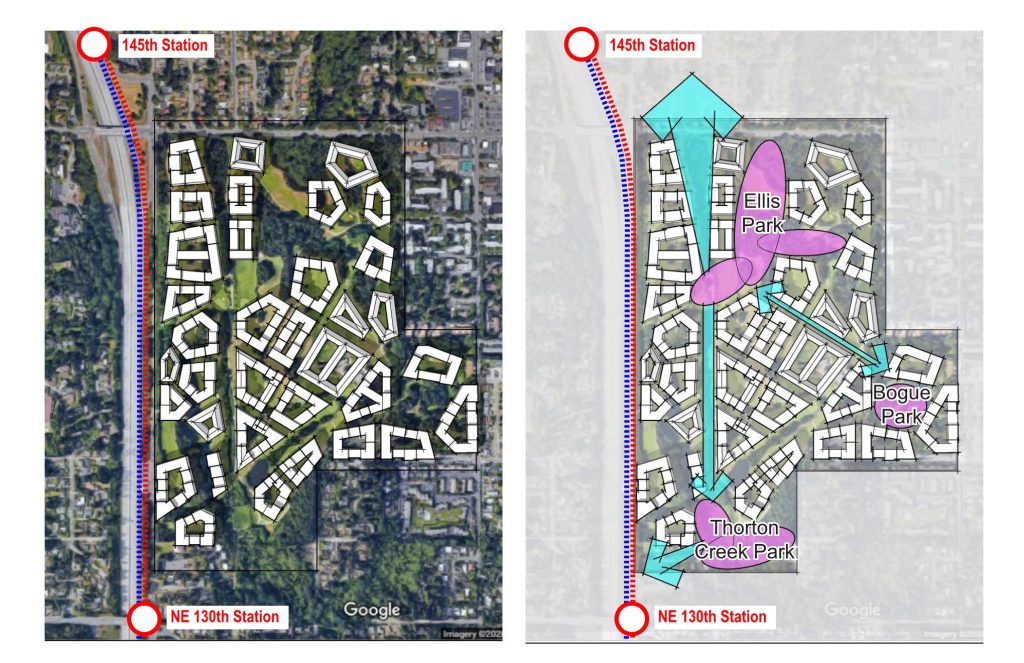

Jackson Park Golf Course consumes toxic pesticides and enough water to fill a small lake, but it has the bones of a good park once we cease the destructive practices needed to maintain a golf course. The trees rise as high as 100 feet and offer a wonderful habitat for nature and human comfort. But those trees only cover 39% of the land. By setting aside 60 acres of the course’s open land for housing, we can create home for 35,000 people, secure affordable housing, provide space for 750 businesses, and preserve more than 90% of the trees for large parks and pedestrian-oriented streets.

Courtyards, woonerfs, boulevards, and large open spaces, the trees would tie together an ecodistrict focused on sustainability. Walkable neighborhoods don’t require street parking and the ecodistrict would supply only a few underground spaces on the edges for residents who can’t make other modes work. Utility vehicles, deliveries, and other necessary auto access can occur through dedicated service streets. Some deliveries may be done by bicycle and retractable bollards would allow for emergency vehicles to enter necessary access points.

Jim Ellis Park Is Born

Developing the course to house a dense neighborhood would also free up land for large public parks. Right now, Seattle declares a golf course a “park,” but you can’t have a picnic on a fairway, or toss a frisbee to a dog, and you certainly can’t get your family on without paying more than $100 in fees. This sounds less like a public park and more like Disneyland. Sixty acres of development leaves 100 acres of open park space. This would benefit the community and the surrounding neighborhoods, businesses, and anyone who got off at the new light rail stop to take a stroll.

It’d also be great opportunity to rename the park. Rather than taking its name from Andrew Jackson–one of our most genocidal presidents–the largest open space could be named after the iconic local transportation advocate Jim Ellis who fought to upgrade Seattle’s infrastructure and convinced a slim majority of King County voters to support a rapid transit network in 1968–if only the threshold hadn’t been set at 60%. Without the groundwork Ellis helped lay, these light rail stops likely aren’t built and Sound Transit may have never existed.

In addition to Jim Ellis Park, smaller parks and open spaces can be enjoyed by the residents and surrounding community. As Seattle commits to make the popular Stay Healthy Streets permanent, the ecodistrict would feature dozens of car-free right-of-ways with large indigenous trees and plenty of space for markets to pop up and for restaurants to spill out.

Let’s Build a Sustainable Community

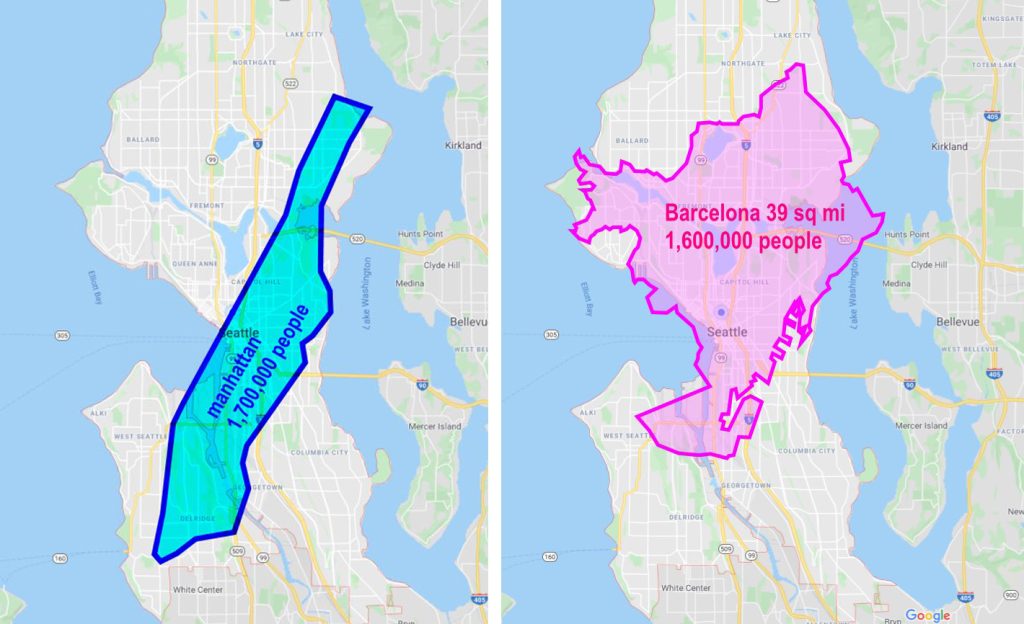

People and vibrancy is what makes cities feel large. Barcelona and Manhattan don’t feel big because of the amount of land they consume, they feel big because there is a lot of dense activity. The one thing they have in common is people and places and how easily the two mix. A ten-minute walk has an enormously positive effect on someone’s mood. So why aren’t we designing our neighborhoods to feature people, safety, and vibrancy?

The most sustainable thing we can do is house people in dense walkable neighborhoods. What Seattle needs is more housing and affordable housing. Public land can leverage this necessary supply and build a mixed-income neighborhood with secured affordable housing. Doing so will fill the need for housing supply of all types and collect millions of dollars to build more transit-oriented affordable housing. In addition to housing supply, this ecodistrict would become an economic engine for the city, supplying thousands of jobs and creating a sustainable neighborhood and tax base.

With 2.5 million square feet of roof space to feature solar panels, over half of the power supply would be generated on site with passive house principles lowering energy needs. Rain capturing would supply fresh water, and the gray water captured from showers and sinks would supply non-potable uses and keep on-site vegetation healthy. If we build with mass timber, the structures alone would sequester 630 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of 1.5 trillion miles traveled by car.

The neighborhood would create housing in our city rather than pushing people into sprawl. For 35,000 to live in this neighborhood we only need 60 acres, and it would be designed around the freedom of transit and walkability. To house them in suburban sprawl, it would take 3,000 acres and they’d be limited to car dependency. Those 35,000 people are moving to the region either way, do we want them to live in Seattle or the suburban fringe encroaching on wilderness?

Seattle has made planning mistakes in the past. But here is our chance to learn from those errors and work towards solving a housing and climate crisis. Developing public land near transit stops for dense, walkable and sustainable housing shouldn’t be a pipe dream, it should be par for the course.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.