“Hey,” she said slowly, pausing as she stepped onboard. “How long has it been?”

Far more people recognize me than I them, and this was another instance. Where had I seen her before? I smiled at her anyway, waiting for my brain to catch up.

I said, “twelve years.” I assumed she was referring, as passengers often do, to when they first saw me. For some reason there’s a tendency in folks to assume this moment was also my first time driving. Maybe it’s because I’m happy. People will eventually stop thinking I’m young… but hopefully they’ll always think I’m new. My stock answer here is to state how long I’ve been driving in total, because who knows? Perhaps they really did find me in my first days on the road. It certainly seemed the case with her.

“Twelve years,” she repeated. “That sounds about right. Maaaan, iss been a while. I remember when you first started this job. And you still here?”

“Yeah, I like comin’ out here. Lil’ different each day, people to talk to…”

She chuckled, looking on in wonder. She was a mother’s age, mildly heavyset with a sweatshirt, ponytail, and baseball cap, and the sparkling eyes of someone around children often enough to absorb their youthful flair, but not enough to be exhausted by them.

“Man, you still doin’ it, huh. You still got that hair! That’s how I recognized you!”

“Ha! It used to be straight when I was little.”

“Huh.”

“But yeah, I try to put out that positive energy, you know?”

“I know that’s right.”

“‘Cause that karma comes back around in unexpected ways!”

“It sure do! You brave though going out there every day, like with that driver* getting shot. I was surprised by that, happening here.”

“Yeah, me too. This’ a pretty good city. I just try to keep puttin’ those good vibes out.”

That’s all I can do. I get varied replies in response to the line; pessimists won’t hear a word of it. Neither will anyone who thinks our actions are meaningless, without consequence. I don’t know what’s true. I haven’t been alive long enough to know if being good has even the slightest effect on our lives. But I know what I want to believe.

But she was no pessimist, and I found her attitude infectious. She whispered: “Oh, you know they ain’t gonna mess with you!”

I laughed. “I got my fingers crossed!”

“Aw, you don’t need to keep em cross’, you got somethin’ special. Something nobody could take away. ‘Cause they would a done that by now if they could. Twelve years. Sheeeeeit. It was the hair! What’s your name again?”

“Nathan.”

“Nathan. It was the hair that did it. I saw from a distance and I said naawww, that can’t be him, from all those years ago!”

“And we’re still here! You’re still here! That’s a modern miracle now, we’re still doin’ our thing day in and day out!”

“One day at a time!”

1. The Question

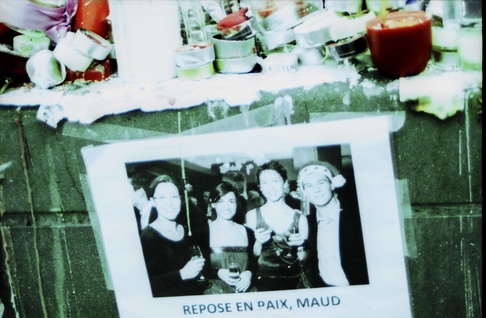

I’ve given the above dilemma a lot of thought. It was a shock to discover some years ago that, to quote Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, “Deserve’s got nothing to do with it.” I used to think if we were good, we’d be fine. Didn’t you? But I remember squatting in front of an enormous impromptu memorial in the aftermath of the 2015 Paris terror attacks, having my own sort of Carlton Pearson moment as I looked at this photograph.

I distinctly recall having the thought: There is no way these young people deserved to be killed as they were.

2. The Fall

That was the beginning. Then things would happen to loved ones of mine, people whose actions I know well, and then to me.

We were struck with violence and implacable death.

And I knew incontrovertibly that neither they nor I had done anything to suffer these iniquities. This realization terrified me, and altered for the worse my perspective on going out into the street every night. I began to assume evil rather than goodness, defaulting to suspicion and fear over the peace that comes with giving the benefit of the doubt.

There’s a colleague of mine who goes out there, on the worst routes, like I do– like I did– enthusiastically, without a care in the world. She’s a trim young woman in her thirties or forties and nobody’s first idea of a tough invincible figure who can fight off anything. But that’s exactly what she is, and she gets her power from her strength of belief. She’s Christian to what I would term a radical degree, religious in her every word and act. She is so confident that she will thrive.

I would look at her and think, I used to feel like that.

I so desperately wished I could be like her again. My confidence had stemmed from a multiplicity of philosophies and spiritualities rather than a religious source, but it achieved the same end: I trusted the world.

I felt like I couldn’t do that anymore, and the most depressing part about it wasn’t that evil might happen to me again, but that I lived in a universe that didn’t appear to care whether evil happened to me, or anyone else. The thought that Cause and Effect might not exist was more existentially terrifying to me than any individual incident. But gradually it occurred to me:

This is a stupid way to think.

It isn’t working very well.

It’s akin to paralysis. I struggled to get through what were formerly the best parts of my day: pulling up to Fifth and Jackson with a welcoming spirit. Saying hey to the guys. Pulling up to Rainier and Henderson inbound with joy, not trepidation.

How did I used to do that?

3. The View

I thought of her often, the driver mentioned above. I may have a contrasting spiritual identity, but I wondered if it was possible to approximate her fearless approach to life nonetheless. How do you put your hand to a stovetop again after you’ve been burned?

I don’t know when I realized it: She isn’t going out there assuming everything will go well. She’s going out there trusting she has the tools to handle whatever comes her way.

What tools do I have?

Of course Cause and Effect are real. What was I thinking? Our actions do have consequences. Haven’t you seen the smile you cause to bloom on someone else, when you smile at them? The dancing shifts of mood you bring as people respond to your tempo, whether it’s thoughtful, kind or cruel? The most powerful tools are not weapons or laws, but ideas. The idea of respect, the idea of kindness; the idea of patience. These manifest themselves in your customer service decisions, and they have more influence than you– or I– realize. You overwhelm (or at least lessen) negative emotions with positive ones.

The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, the psychologists say; maybe that’s no less true of the universe at large. Didn’t you always manage to make it through your challenges, fraught and insurmountable as they felt at the time? Let me not be blind to the glimpses we find with hindsight, glimpses that show it really was for the best that it worked out this way. That you might even be better for it now, as brutal as that is to say aloud.

On a vaster scale, you can feel the mysterious multiplying effect of being good coming back around. I see it about me gently, like a mirror refracting light. Sure, I don’t understand how it works. Sure, things happen that don’t make sense.

But who am I to assume that because I don’t see order, it must therefore not exist? If I am part of existence, how can I objectively comment on it? Where was I, after all, when this earth was forged? And don’t we see echoes of the sublime all around us? Tell me you don’t see something incalculably true being communicated when dappled rays of sun shine through trees. When the stark and welcome beauty of the clouds stops you in your tracks, whispering to you in a language beyond words: “there’s more than you know.”

There is a process inside me that’s happening slowly. It worked before, my body says. I seem to be returning to my old easy happy confidence, but with a melancholic openness I don’t have words for. What can I do but take life as it comes, and make the best of it? How could it not help to take things less seriously, to lean toward the light and with laughter?

Give me time. I’m getting closer.

—

*My friend Eric Stark, whom you may have read about last year. Thank goodness our buses don’t have driver barriers; if we did, Eric would’ve been unable to take cover from oncoming bullets and would certainly have died.P

Nathan Vass is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, and author by day, and a Metro bus driver by night, where his community-building work has been showcased on TED, NPR, The Seattle Times, KING 5 and landed him a spot on Seattle Magazine’s 2018 list of the 35 Most Influential People in Seattle. He has shown in over forty photography shows is also the director of nine films, six of which have shown at festivals, and one of which premiered at Henry Art Gallery. His book, The Lines That Make Us, is a Seattle bestseller and 2019 WA State Book Awards finalist.