Over this series of articles, I have laid out an argument that Seattle should mix industrial uses in our residential and commercial neighborhoods. A long history of exclusion keeps interesting and useful things out of our communities, an absolute loss for building a vibrant and vital city. Now is the time to change this because the lines have disappeared between the places we work, create, build, and live. Right now, every neighborhood is mixed use.

- Read part one of the series here introducing the concept of neighborhood industrial use.

- Read part two showing how zoning has been a terror since it was permitted in the United States.

- Read part three showing that the way we apply zoning through a broken and malignant use table is a joke.

- Read part four showing what a cool neighborhood industrial use can look like, but recognizing the heavy legislative lifting to make it happen.

Which begs the question, why does a terrible zoning ordinance or the potential of a cool new building necessitate change? We have spent a century putting industrial uses in very specific places. Seattle seems to be chugging along pretty well without having haberdasheries and cobblers on every street corner. Why change that now?

Because our city’s not actually chugging along very well. Our zoning perpetuates many of the problems we’re experiencing, from expensive housing to declining industrial jobs. All this is exacerbated by coronavirus. The most basic foundation of zoning–the hard separation of uses–actually breaks the city and makes every discussion of development into a death match.

The Zone of Maximum Conflict

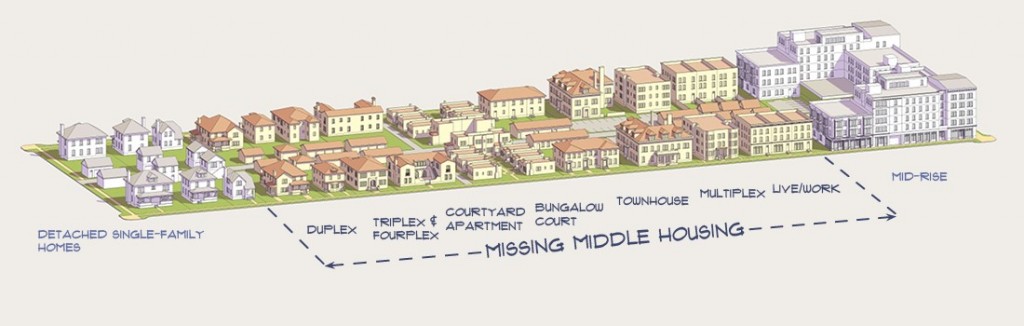

We have an idealized image that urban development should taper up to more intense uses, with stages of growing height and heavier use going from a hinterland to a dense urban core. We imagine urban development being a spectrum. This is supported by everything from the original development scheme in SimCity through our current infatuation with the Missing Middle typology.

While we imagine this spectrum of density, the way we write our zoning ordinance prevents gradual intensification. We create groups of disfavored uses, defined broadly and outright banned. We impose hierarchies that conflict with one another. We carve out exceptions that are so narrow as to only impact a single building. We whittle down zones to specific lot lines, then lock those restrictions into perpetuity. We defer design decisions to the neighbor with the most restrictive zone.

The result is that the vast majority of land in the city defaults to the most exclusionary use: single family detached housing. This presses the disfavored, intense, or expansive uses into small clusters and forces competition for land between uses that shouldn’t be competing. Officials can talk all they want about saving good paying industrial jobs, but it’s mainly lip service if zoning forces big-box wine shops and mini-storage on industrial land.

More acutely, our zoning puts low density homes right against the uses zoning was designed to separate. By removing the ability to gradually intensify, we’ve caused more conflict. All of the pressure that could be dissipated with gradual increases condenses into a zone of maximum conflict.

Such segregation of uses pushes necessary, vital businesses far from most of the residents that use them. However, this does not stop the uses from appearing in neighborhoods. It sucks to drive across town to do stuff we like, so we bring stuff we like into our homes. Industrial uses are all over residential areas. From catering kitchens to massage parlors to climbing walls. From distribution centers to gyms, workshops to metal forges. Everything is allowable, if it’s wrapped in a single-family detached house.

This is the inherent paradox of zoning: insular single family homes violate the zoning that protects them. Having an otherwise excluded use raises the value of the most exclusive homes. Zoning does not separate residences from noxious uses. Zoning simply atomizes noxious uses into private compounds, while pushing services out of the area. This makes the whole neighborhood wealthier and poorer at the same time.

We can do so much better. The same uses that get built into ritzy vacation homes should be permitted in any residential zone. Eliminating the bright-line exclusion of industrial uses from neighborhoods is fundamental to reclaiming a green, fair, and vibrant city.

A Greener City

Neighborhood industrial is a foundation of the green economy. Bringing useful things into our neighborhoods allows all of the benefits we can expect from reducing commutes and parking. Creating a community that is active all day evens out the demand on electricity and water. Neighborhood industrial will use the infrastructure we have throughout the entire day, and not leave behind empty homes being cooled or long pipes filled with water and waiting until the evening demand.

The mechanism with which we allow neighborhood industrial is also a way we green our communities. We cannot rely on industrial zoning to simply sweep smelly uses out of sight. Neighborhood industrial will require management plans to identify and mitigate potential sources of noise or discharge. Manufacturing and industrial processes, including everything from the water outflows at a brewery to a chalk eater at a climbing gym, can be monitored for how well they’re controlling pollution. With neighborhood industrial, we will expand our pollution testing and monitoring systems.

Right now, the most local real-time monitoring we have in the city is morning and evening traffic reports. These change behaviors, making people choose different routes or delay their commutes. It also says a lot about what matters to us. Our counts are about how many cars are going by particular points. They’re not measuring the spewed noxious gasses. They’re not measuring the lives lost in crashes. Without measuring a problem, we deny it exists.

Management plans in neighborhood industrial will let us do better. Connect the sensors and monitors required by these management plans to create dashboards for every neighborhood, making real-time testing and reporting of air, water, and noise not just possible, but a priority. That way we can adjust our behaviors, just like we do to avoid a traffic backup. It should not take a special study to track particulates. It should not take a decade to figure out an ongoing dumping conspiracy. Real time reporting will allow residents and businesses to make meaningful decisions about their own activities to flatten the curve, to coin a phrase. And if you’re a business owner in the neighborhood you live, your decisions will be particularly meaningful. By bringing neighborhood industrial uses into communities with management plans, we will build the mechanisms to track our progress.

A Fairer City

Data-driven responsiveness will make our city fairer. By defaulting to single family residential across so much of the city, zoning simultaneously tries to sweep all pollution into a tiny corner. Out of sight, out of mind. Except for the predominately black and Hispanic populations that live in the distressed communities directly down wind.

To understand a zoning code is not some great insight in urbanization and human society. Instead, it is peeling back onion layers of institutionalized racism and calculated bias, with all the weeping that entails. Americans try to manage the city through zoning, because zoning is the bluntest tool available. We insist on throwing it against every urban problem specifically because its wide margins cloak the racist impacts with economic justification. Zoning is not a tool, it is a weapon.

Neighborhood industrial will disarm that weapon. Allowing for a ground floor candy shop is not going to solve racism. But we bundle together race and class and a thousand other biases when we talk about “neighborhood character” and “nature of the community.” Neighborhood industrial is about uncoupling real, measurable pollution and nuisances from the thin justifications of character and desirability. It shortens the list of excuses for sweeping people of color and smokestacks into the same corners of the city. If that makes some folks confront that their actual desire is keeping brown folks out of the neighborhood, all the better.

The fairness also works in other directions. Our current industrial areas like Interbay and SoDo are located because of water, highway, and rail access. Businesses that need this expensive publicly funded infrastructure should not be forced into competing for the same space with mini-storage and big box stores. Whole Foods and Michael’s are not looking for access to marinas, they’re looking for favorable zoning.

It happens small, too. Surrounding the new four story loft West Woodland Business Park on the 1200 block of NW 52nd Street, there are three breweries (another around the corner), the RAD electric bicycle shop, and the relocated Serious Pie outlet. This would be an incredible block in any neighborhood and should be constantly busy with lots of homes right there. But we have relegated it to an industrial zone between a Vaupell plastic prototyping and Bardahl Manufacturing. These businesses take a full block of our precious industrial zoning, separate from most of residential Ballard, and add to land value pressure on nearby industries. That’s unfair to Bardahl, unfair to the breweries, and unfair to us. And every one of those breweries is very good. Making space for them in our residential zones would be an all around benefit to the community.

A Vibrant City

But mostly, neighborhood industrial uses are awesome. That’s why people put them in their homes. We love making stuff. We love watching stuff get made. We love buying stuff that our friends make. We go on vacation to places where people make stuff. As the sign says downtown–at Seattle’s mixed commercial, industrial, and residential Pike Place Market–we love to “Meet the Producers.” And it’s pretty cool to live next to them too.

Communities that make things are beautiful. And we have some very good examples. Hackeschen Hofe in Berlin is a early-20th century low-rise apartment building. Inside, the series of connected courtyards are surrounded by small workshops and shops selling things they make. As shown in Sightline, there are American examples of residential communities forming in industrial areas in Portland and Denver.

It’s easy to see the key to this development in reused industrial properties. In Baltimore and Boston, abandoned mill buildings are converted to offices and apartments. In San Antonio, the old Pearl Brewery has turned into a mixed use development. In San Francisco, reclamation of Pier 70 is underway with industrial, retail, and residential development. In our own Pioneer Square, old loft manufacturers are now apartments. These high-ceilinged, well built structures are full of windows and wide open spaces. These are beautiful places built from factories. The structures offer a flexibility that is just non-existent in the buildings we construct to fit current, confining zoning ordinances. It’s a flexibility in structure that we’re going to need moving forward.

The Recovered City

Which brings us to the current pandemic. We cannot close out any discussion today without recognizing that we are all at home. Far too many of us have seen our businesses and workplaces close, some permanently. If we are lucky enough to work, we are doing so from our kitchen tables or desks in our bedrooms. We’re told that we’re going to restart, that we’re resilient. It’s hard to see when we’re separated by a virus that makes busy urban places a fantasy.

What’s more difficult is to expect our recovery will dump us into exactly the same situation that we were in back in January. Too many people are ready to work from home permanently, and companies are following them. Too many cornerstones of retail are shuttering, and replacements are not coming. Too many enormous factories and warehouses are vulnerable, and they are being lapped by small and responsive alternatives. The distance we go for necessities is decreasing, and we’re rethinking our neighborhoods.

These changes are not possible in the zone of maximum conflict. Recovery is not possible if we keep our hardline, inflexible zoning.

This may seem to contradict our need to fortify our homes. While an understandable reaction, the pandemic shows that we pay for our safe little fortresses in other ways. By making everyone go to the exact same place for toilet paper, or meat, or church, our screwed up zoning creates massive vulnerabilities to coronavirus. The zone of maximum conflict concentrates low wage employment, promotes long distance travel, and disjoints social networks.

Neighborhood industrial can begin to mend these issues by addressing the underlying failures of zoning. We can dismantle and address the historic prejudices that drew broad rules to exclude disfavored people and uses. We can scrap the terrible use tables that are less regulations and more footnotes and exceptions. We can install mechanisms of flexibility and data driven responsiveness to stop hiding pollution and start protecting residents and the environment.

Cities take work and can be exhausting. We spent a century looking towards zoning to streamline the difficulties; to sweep the noxious uses out of sight, to demolish the slums, and to sequester the different people in an effort to “protect” the neighborhood. But in doing so, we cut to the quick and eliminated the buffers and extras that can only be found in cities. We don’t have the other store or the small workshop to iron out the bumps when the huge supply chains fail. In the name of efficiency, we ended up erasing the redundancies that actually protect the neighborhood.

Neighborhood industrial corrects the ways we overused zoning and scraped communities down to the residential bones. As we spend each day in our homes that are doubling as workplaces, gyms, schools, broadcast studios, craft galleries, and screaming booths, we can feel the places where our neighborhoods are thin. Coming out of this pandemic, let’s correct that. We may not really need to have a brewery on every corner. But the pandemic is showing how our most resilient communities have the flexibility that allows for one.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.