In the midst of the lively local restaurants and coffee shops on N 45th Street in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood is a business bearing the logo of a famous multinational corporation.

State records indicate that discharges from this business have been contaminating the groundwater flowing into Lake Union with benzene, a known carcinogen and fish toxin, at a level more than 360 times the legal limit for at least 10 years. Its vents spew benzene vapors at the window of a neighboring house just 10 feet away and at the tightly packed, expensive homes clustered nearby. Assuming industry averages, 6 million pounds of carbon flows from the business into the atmosphere every year. Could such a business really get away with such copious and hazardous pollution in progressive, environmentally-conscious Seattle?

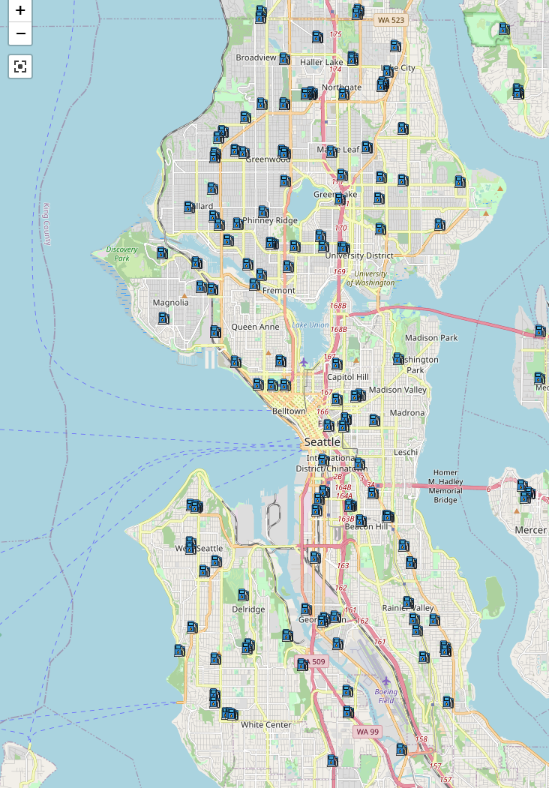

The business is the Wallingford Shell gas station, and its pollution is typical of gas stations throughout Seattle. A survey of Seattle gas stations’ environmental records reveals that 74 of 109 gas stations have a documented history of contamination of the soil or groundwater. Forty-eight of those gas stations have single-walled underground gasoline storage tanks installed before 1990 that are past their useful life and at high risk of leaking. The Wallingford Shell’s tanks are single-walled and were installed in 1984.

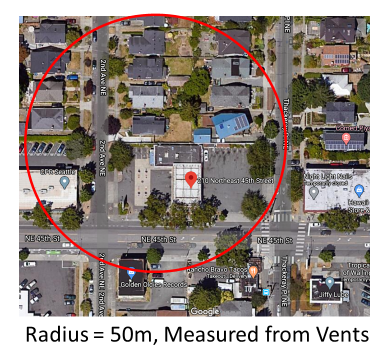

The problem isn’t confined to the tanks. Gasoline drips and small spills from fueling are a routine occurrence at gas stations, and the spilled gasoline finds its way into stormwater and groundwater. Gasoline vapor leaks while customers pump gas or during tanker truck fuel deliveries are common. A recent study of fuel vapors emitted from gas stations found that benzene levels emitted from underground storage tank vents were at unsafe levels up to 150 meters from a gas station. Roughly half the carbon which Seattle emits passes through its 109 gas stations.

Should Seattlelites accept such pollution as just another consequence of our addiction to gasoline? No. We can and should stop much of the gas station pollution by strictly enforcing gas station pollution laws already on the books. We should also stop the spread of gas stations by prohibiting the construction of new gas stations citywide because the 109 we have are more than enough. These steps will make our city cleaner and healthier, alleviate our housing problem, and help us achieve our carbon goals.

Our state government already has the statutory right to 1) prevent releases of gasoline and other hazardous substances into the air, soil, and water; 2) order cleanups of gas station pollution; and 3) order the polluter to pay for the cleanup. Unfortunately, the state rarely exercises these regulatory powers. Instead, it lets gas stations get away with loosely-enforced voluntary agreements which put the polluters in charge of how and when cleanup occurs. In the case of the Wallingford Shell, Shell Oil Company has evaded its voluntary cleanup obligations for more than 10 years, while the station keeps operating.

Instead of allowing Shell and other gas stations to kick the cleanup can down the road, the state should enforce cleanup requirements. If polluters won’t or can’t pay for cleanup, the state should close the station, do the cleanup itself, bill the owner for the costs, and lien the land if the bill isn’t paid.

If the state enforces the law and the pollution is cleaned up, the owner of the gas station property will have a strong incentive to sell the land for another use rather than spend millions to comply with the cost of modern storage tanks, piping, pump, and stormwater systems, and again risking contamination of the cleaned-up site.

By forcing gas stations to comply with the law, the state can eliminate the enormous subsidy the entire oil industry receives by allowing gas stations to foist their considerable pollution onto neighbors of the gas station and the fish and wildlife affected by the toxins.

In sum, forcing cleanups and banning new gas stations will result in a triple win–improving public health by eliminating a major source of pollution, shutting off a gushing carbon spigot, and redeploying scarce land for desperately needed housing. It’s time to demand that our state and local government eliminate these widespread threats to our health and our future.

Matthew Metz is co-executive director of Coltura, a Seattle-based nonprofit working to phase out the use of gasoline.

Matthew Metz (Guest Contributor)

Matthew Metz is the founder and executive director of Coltura. Metz founded Coltura after purchasing his first electric car and wondering why his friends weren't also making the switch. Prior to founding Coltura, Metz founded the Metz Law Group, Jaguar Forest Coffee Company, the Central Area Development Association, and the Central Area Arts Council. He also worked in international development for an NGO in Mexico City. Metz is a graduate of the University of Chicago and UCLA Law School, and is the author of the citizenmetz blog, a blog focusing on the intersection of carbon and culture.