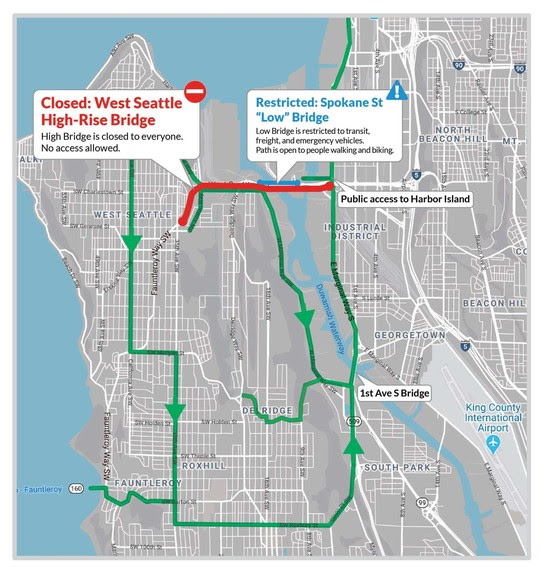

Yesterday, West Seattle got more bad news as the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) announced the West Seattle Bridge would be closed for at least two years to allow for the extensive repair work it needs.

Even worse, SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe cautioned it may not even be possible to salvage the bridge if the damage is too extensive. “It may not be possible to repair the bridge as it currently is,” Zimbabwe said, giving a nod to not just to the technical challenges but also the looming question of the “financial feasibility of repair.”

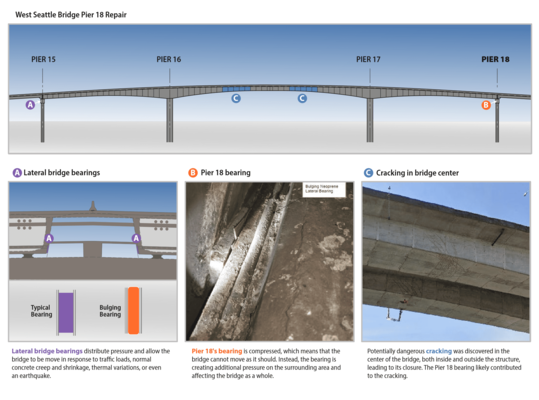

Further analysis will give us a fuller picture of the West Seattle Bridge’s salvageability. For now, we know that shoring up Pier 18, one of the primary supports of the bridge, is immediately needed, as Zimbabwe explained in a presentation.

Regardless of what the engineers find, the best path forward in the West Seattle Bridge’s deteriorating situation may well be starting from scratching with a brand new bridge designed to carry light rail as well. That would provide an elegant solution, helping to fund SDOT’s unexpectedly urgent megaproject while also possibly speeding up the West Seattle Link’s opening date.

In the meantime, emergency repairs may allow the bridge to reopen in a few years time while the new bridge is designed–again depending on what the engineers find. The bridge has already been closed for almost a month since Mayor Jenny Durkan and SDOT revealed the structural issue on March 23rd.

Going the route of repair may not buy the bridge much time. As Heidi Groover and Mike Lindblom reported in The Seattle Times, according to Zimbabwe the best-case scenario is to complete repairs that keep the bridge in service for another 10 years. Zimbabwe also cautioned that the crossing, which opened to traffic in 1984, will definitely not reach its full 75-year design life.

A bridge for everyone

The West Seattle Bridge’s shrinking lifespan is why the City of Seattle must embark on a comprehensive plan to serve West Seattle’s needs, as we’ve argued is necessary in Interbay, too. Transportation projects must serve our long-term goals and how we envision people getting around in “the city of the future” that Mayor Durkan often invokes. And where we’re heavily investing public resources, we must also plan for growth to further our goals around equity and housing for all.

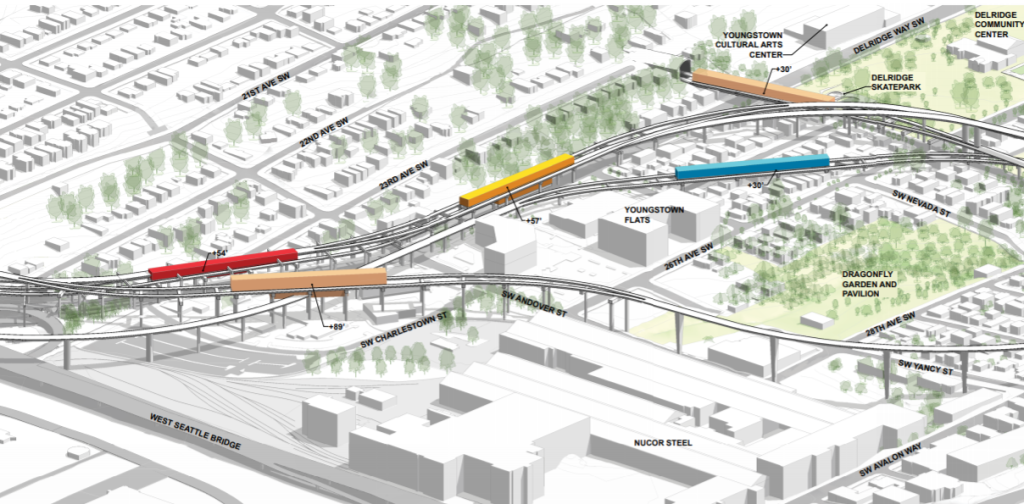

West Seattle Link is tabbed to open in 2030 which means the West Seattle Bridge will need to be replaced on roughly the same timeline as Sound Transit aims to open light rail service to West Seattle. Why not construct a single bridge to serve both light rail and general traffic? And perhaps it could offer another all ages and abilities bike route into West Seattle and one that makes the climb to Alaska Junction more gradual than other options.

Granted Sound Transit 3 (ST3) timelines were set before passage of a $30 car tab initiative and the coronavirus pandemic caused slowdown to construction and the tax receipts that fund it cast considerable doubt on those schedules. Still combining SDOT and Sound Transit funds could be a way to make both projects more feasible.

For Sound Transit, piggybacking on a new West Seattle Bridge would solve one of the stickiest issues in planning ST3. The agency prefers a high bridge for West Seattle citing cost concerns, but several vocal West Seattle stakeholders fought to get a tunnel option included in the environmental study that will determine the project’s fate. Sound Transit estimates a tunnel would add at least $700 million to the project’s cost, require third party funding, and likely take longer.

That said, Sound Transit’s preferred stand-alone fixed high bridge isn’t without its issues too, which include where to site it given close proximity to Port of Seattle operations on Harbor Island. The existing elevated option also is likely to require more property acquisitions. A combined light rail and automobile bridge would lessen the need for property acquisition and the conflict with Port operations.

A combined bridge could be an elegant solution and one within Sound Transit’s ST3 budget. Perhaps it could even speed up West Seattle Link’s opening so that we can reap the transit benefits sooner.

Crafting a transportation levy to fund it

The West Seattle Bridge cost $150 million when it was built in 1984. In today’s dollars that’s about $375 million, but construction cost inflation has likely been greater than monetary inflation alone. SDOT does not have the funding for the $23 million in needed emergency shoring work it has already identified, let alone the money for full repairs or a replacement bridge. However, a West Seattle Bridge is likely to become a top priority given how big of a part it has played in the city’s transportation network.

SDOT will likely need to advance another transportation levy to fund the West Seattle Bridge repairs and replacement. That newfound funding need will join a long wishlist that includes a Magnolia Bridge replacement, potentially a Ballard Bridge replacement, another batch of RapidRide upgrades for popular bus routes, and, one would hope, continued progress to our pedestrian and bicycle master plans.

Given the tumultuous rollout of Move Seattle Levy projects, SDOT didn’t do itself any favors in getting another vote of confidence in a levy likely to exceed a billion dollars. Still, a signature project like a West Seattle Bridge that accelerates light rail timelines could help propel the measure to passage–particularly if it goes to ballot once the economy is picking up steam again from this recession. The alternative of letting our bridges fall into the sea doesn’t seem too attractive either.

Why did the West Seattle Bridge fail so soon?

It’s been noted that the winning construction bid back in the 1980’s came in under budget, which has fed speculation that the contractor may have been desperate for work amid the recession and subsequently cut corners to make the skimpy budget work.

Another culprit that’s been kicked around is the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, which SDOT says lowered the bridge three inches at the time and may have ultimately sped the deterioration of its structural integrity. Shoehorning an extra lane of traffic on the bridge may have accelerated the aging of the bridge further–yet again showing the ‘add another lane to solve traffic’ mentality is self-defeating. (The new bridge shouldn’t go fall into this trap: two lanes in each direction will likely suffice.)

Whatever the reasons, the hoped for 75-year lifespan of the bridge has proven to be a pipe dream. Bridges that carry 100,000 cars per day take a beating. The comprehensive planning the City undertakes around the bridge’s replacement must involve prioritizing transit to increase ridership, lighten the load on the replacement bridge, and decrease carbon emissions so the City can meet its climate goals–our current trajectory isn’t promising.

Immediate fixes

For now SDOT has a complicated set of repairs to make just to ensure the West Seattle Bridge doesn’t fall apart–potentially collapsing into the Duwamish River. SDOT posted its repair plan on its blog; in short, it involves creating temporary supports to shore up the structure to allow the agency to tear out the old bridge bearings in Pier 18 and cement new ones into place.

This would be only the first step in saving the bridge, and the later steps aren’t even known yet. That’s why Seattle should begin making contingency plans in case the West Seattle Bridge can never reopen. Let’s get the next generation of bridges right so we’re not contemplating overhauls or managed decline while bridges are still in their 30’s. If done well, engaging in comprehensive planning that includes designing for light rail and other multimodal improvements on the new West Seattle Bridge would help ensure residents of West Seattle remain connected to the rest of the city long into the future.

The featured image of the West Seattle Bridge is courtesy of SDOT.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.