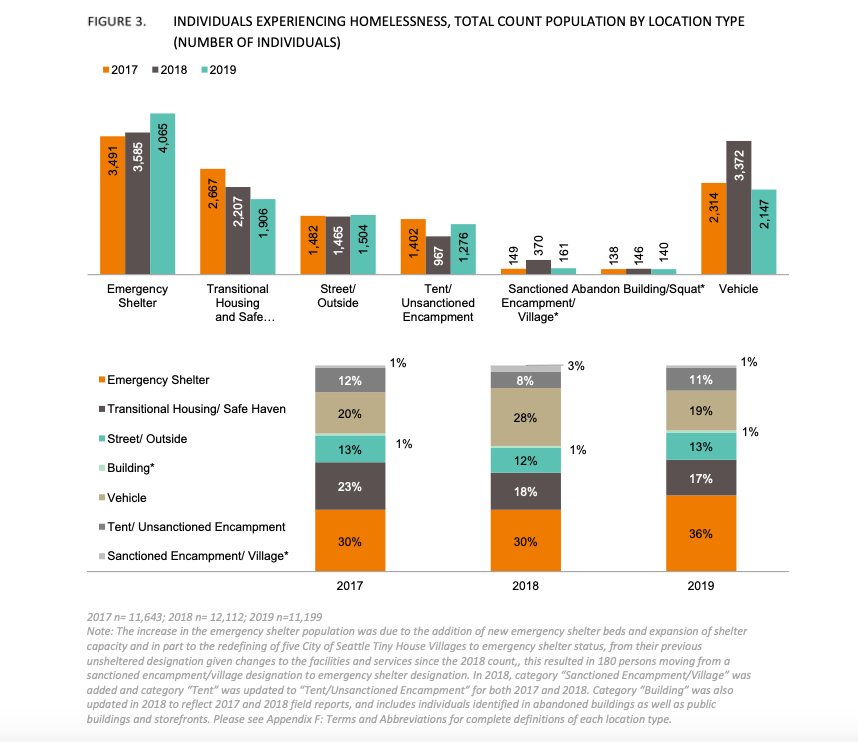

It is never easy to live unsheltered. Research shows that the stresses imposed by homelessness prematurely age the body by 10 to 20 years beyond individuals’ chronological age. But in the time of COVID-19, life on the street has become an even heavier burden.

“We are not giving them any means to protect themselves in any way at all,” said Brittany Meek, Clinical Programs Entry Services Manager at the Downtown Emergency Service Center (DESC), who reported to the Seattle City Council’s Select Committee on Homelessness Strategies and Investments during an April 8th meeting.

Throughout the meeting, Meek and other service providers painted a stark reality for the public officials. A man recovering from brain surgery unable to clean the dirt off the sutures in his skull. A woman trapped in her tent because she had menstruated on her clothes and was unable to clean herself. Requests for hand sanitizer denied because of supplies vanishing in the face of demand. Outreach staff working long hours in the field forced to relieve themselves in bushes and alleyways.

“It’s arguable that being able to use the bathroom is just as much a human right as access to food,” said Dawn Whitson, an outreach worker with Evergreen Treatment Services.

Unfortunately, even before the COVID-19 outbreak shuttered the businesses, public buildings, and community organizations that provided some public access to bathrooms, lack of access to bathrooms and other hygiene facilities was already identified as a major problem for the city’s homeless population.

Back in 2019 a report on the City of Seattle’s Navigation Team services completed by the City Auditor found that the availability of 24-hour restroom access to be severely lacking for people who sleep unsheltered on Seattle’s streets. Using a metric created by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), which states that “there should be at least one toilet for every twenty persons” and that toilet facilities should optimally be located somewhere between “six and fifty meters away from each household,” the auditor found that Seattle would need to add access to an additional 224 toilets to meet the basic needs of its homeless population.

Imagine for a moment living in a situation where you shared access to a single toilet with twenty other people. Not exactly glamorous, right? Now imagine living in a situation where that kind of access seems like a distant dream.

Seattle has a long history of struggling to provide restrooms for the public to use. In 2004, the installation of just five high-tech self-cleaning toilets in Downtown and Capitol Hill resulted in a $5 million dollar failure only a few years later, after complaints of drug abuse and prostitution led to their removal. More recently, protracted controversy around the proposed installation of a Portland Loo style public bathroom in Pioneer Square led to the project being abandoned. The issues of restroom access for the homeless has been so acute for so long in Seattle that some residents, like Mark Lloyd who was profiled on NPR last year for his “guerrilla toilet distribution project,” have begun taking action.

“Everyone should have access to a working toilet and a place to wash their hands within a half mile of where they live,” said Alison Eisinger, Executive Director of Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness. However, such a modest declaration can feel unattainable when the fact Seattle only has six permanent public restrooms open for 24-hour access across the entire city is taken into consideration, especially since data shows that each night thousands of people sleep unsheltered on the city’s streets.

What can Seattle do to confront the current crisis?

The City of Seattle has been taking steps to increase access to hygiene facilities for the homeless. Six new hand washing stations and fourteen portable toilets have been added since the COVID-19 outbreak. Public access to more than 100 restrooms is supposed to have been maintained in the city’s parks, although some restrooms remain closed due to seasonal closures and lack of staffing. Currently five community centers, which are open for limited daytime hours, offer access to showers.

During the April 8th meeting, Councilmember Teresa Mosequeda shared the idea of reopening the all of the City’s 26 community centers for restroom access with staffing from the National Guard, an idea that was met with cautious support from advocates who warned that opening community centers alone would not be sufficient as a solution.

Eisinger and other community service providers have advocated for reopening public buildings, including libraries, in lieu of ordering more portable toilets and hand washing stations, which can be expensive and difficult to clean and maintain. According to Deputy Mayor Casey Sixkiller, the City has estimated that each portable toilet site costs a whopping $35,000 per month to operate without staffing, with costs climbing further as staffing increases.

An evaluation rubric, which can be used to gauge the viability of both public and private buildings as potential sites for public restroom access, has been created by the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, which Eisinger has offered to share with the City.

The notion of calling for private businesses, restaurants in particular, to offer their facilities for public restroom use is controversial. While such a move could go a long way in providing much needed restroom access, it also would present public health challenges for restaurant service workers and customers.

“It was a bad public health policy before COVID, and I don’t believe it’s the right strategy now,” said Councilmember Mosequeda, calling for the City to consult with public health experts before moving forward with a plan for businesses to open their restrooms for public access.

However, as Washington State’s “Stay Home, Stay Healthy,” order continues at least into early May, it is clear that without major changes, lack of access to bathrooms and hygiene facilities will continue to make homeless people, who are already at high risk for COVID-19 transmission, even more vulnerable.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.