A gondola tram could be the ideal way to deliver West Seattle’s Sound Transit 3 stations without unnecessary expense and complications of light rail–and with early delivery rather than delay.

Voters may not have realized when they approved the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) package they locked in a one-size-fits-all “solution” to every geographical problem. That includes forcing a technology designed for gentle topography–rail–into some of Seattle’s hilliest terrain: West Seattle.

Sound Transit should be allowed some modal flexibility in case terrain challenges, financing and/or other issues arise between now and the 2030 targeted delivery date of West Seattle light rail. The lack of flexibility explains why Sound Transit’s Cahill Ridge announced at West Seattle Transportation Coalition’s (WSTC) November 2017 public meeting: “We have no Plan B.”

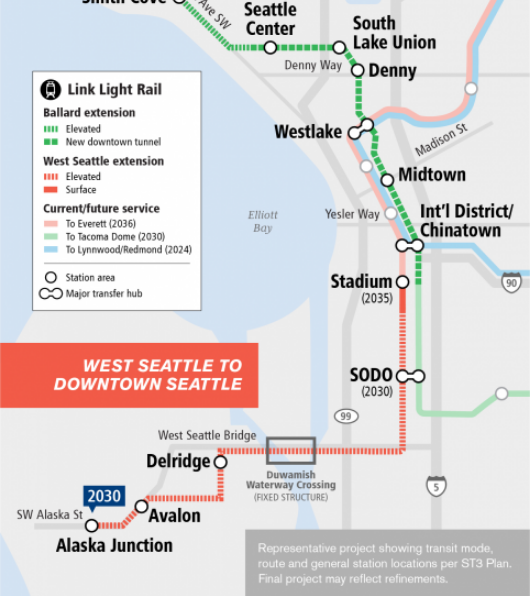

To get light rail from SoDo to West Seattle will require a third bridge, parallel to and taller than the current 140-foot-tall high bridge, in order to span the cement plant, warehouses, marina and Duwamish Waterway. It will drop at Pigeon Point and snake up in a maze of ramps and towers to 400 feet of elevation in barely a mile. Here’s one vision of what that could look like.

History of West Seattle’s Transit Efforts

When the Jeanette Williams high bridge (1984) and the Spokane St. low bridge (1991) were built to the “out of the way” West Seattle Peninsula, neither design included space for light rail track. In 1968 and 1970, Seattle voters rejected Forward Thrust’s light rail network and the federal funding attached to it. Between 1997 and 2005, voters approved a Ballard-West Seattle monorail expansion five times, but it never got built.

Today, nearly 100,000 people live on the Peninsula–almost 15% of Seattle’s population. The West Seattle Bridge Transportation Corridor is the city’s busiest outside of I-5 (with 10,000 to 14,000 vehicles per day on the low bridge and 100,000 to 110,000 on the high bridge) and West Seattle needs more commute options. Voters settled on ST3 to do the job in 2016. But another option or mode would be better suited to this hilly terrain.

King County Councilmember Joe McDermott suggested tunneling at last October’s ST3 Elected Leadership Group (ELG) meeting. Backed by West Seattle residents and WSTC, tunnels produce less elevated eyesore, less operational noise, and more surface area for housing. Light rail travels in a tunnel under Downtown, the U District, and Roosevelt. But the ELG rejected the idea, citing lack of funding. So residents and WSTC proposed eliminating one of three planned ST3 stations, and applying the saved money to tunneling. Sound Transit has not replied or entertained the idea.

Since 2015, WSTC has advocated for rebuilding the high bridge interchange with SR-99–to add a northbound bus-only lane, and a SR-99 exit south. Buses offer more flexibility and less capital expense than light rail. In 2017, WSTC board members asked landowners under the interchange if they’d support a rebuild. They said yes, if Sound Transit could minimize business impacts and provide compensation. That option has not advanced.

West Seattle Aerial Transit

So we look “outside the box” at aerial transit: proven worldwide, grade-separated, enough capacity for West Seattle, and 50% to 80% cheaper than light rail. It is not slope-challenged, and could be delivered to West Seattle sooner–perhaps by 2025 if Sound Transit proceeds decisively. Seattle engineers and bloggers have advocated since 2012 for aerial to branch off from, or connect to light rail and bus lines, e.g., from Capitol Hill to South Lake Union and Seattle Center, from the Waterfront to Capitol Hill, to First Hill, and within and beyond West Seattle (Seattle Transit Blog, CityTank, The Urbanist). The Gondola Project has championed aerial transit since 2009.

Rather than rob Peter (eliminate stations) to pay Paul (fund a tunnel), it makes more sense to use a more appropriate, far less costly option. Seattle’s underground, three-mile U Link extension cost $600 million per mile; Honolulu Area Rapid Transit’s 20-mile elevated cost $500 million per mile. A typical 3S (three cable, continuous-circulation) aerial system runs $20-$64 million per mile, depending on capacity and stations, according to the Gondola Project. Portland’s one-mile gondola cost $57 million.

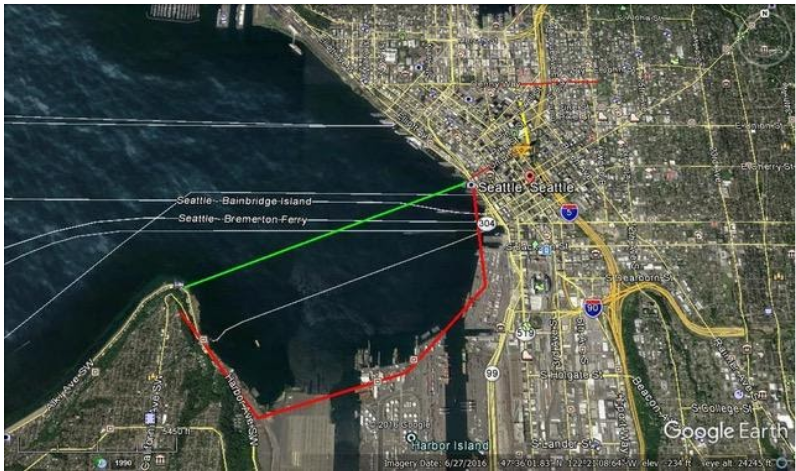

Six years ago, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) talked with aerial transit builders about running a line across Elliott Bay from West Seattle to downtown (see map). “The potential for ridership always appeared strong,” said SDOT Waterfront planning director Marshall Foster, “especially if Metro shuttle service could connect West Seattle to the station on the west side.”

The concept was rejected: its route and 700-foot tall pylons would create issues with shipping, cost, views, environment and permitting. SDOT also considered aerial from the Admiral-Hiawatha playfield area, crossing Harbor Island, and connecting to Starbucks and the stadium area.

In 2017, the WSTC board discussed more commuter-centered routes with Dopplemayr, builder of Portland, Oregon’s system. As most West Seattle commuters head eastward from the Alaska-California Junction, the routing would start from a station near The Junction, glide down to a Delridge station, then cross the Duwamish on Harbor Island, and land at a Starbucks and/or Stadiums stations, to connect with light rail. It could also connect with light rail in the International District.

A 3S system would probably work best for West Seattle Aerial Transit (WSAT). It can carry 35 to 40 people per car, at speeds up to 25 mph, with short headways, and capacities of up to 6,000 people per hour. It would require fewer support columns than light rail, smaller stations, and minimum disruption of existing urban infrastructure, such as small businesses and residences. The detachable 3S design can turn corners, run with intermediary stations, and tolerate 65 mph winds. Later WSAT designs could extend south from Delridge Station to serve the Delridge corridor and White Center, link east to Morgan Junction, and head north to serve Alki, and/or Admiral.

Sound Transit has compromised on station locations and routing options, but has stuck to the “You can have any mode you want as long as it’s rail” theme. This appears to be the fault of too-narrowly written legislation. With funding squeezed by I-976, federal stinginess, and construction cost escalations, the safer move would be to opt for a proven, more appropriate, less expensive alternative that could be delivered sooner. While the choice seems clear, Sound Transit continues to advance West Seattle light rail plans. Rather than let inertia carry us toward overbuilt light rail, Sound Transit should add West Seattle Aerial Transit into the mix and let the environmental impact statement show the respective advantages.

Martin Westerman (Guest Contributor)

Martin Westerman has authored two environmental business books and dozens of articles, taught green business and communications at the UW Foster School of Business from 2000 to 2008, and currently serves on the boards of the the Seattle Green Spaces Coalition and the West Seattle Transportation Coalition. He lives in West Seattle.