For decades, the pedestrian connections between Uptown and South Lake Union were limited, thanks to the design of Aurora Avenue–SR-99 to a motorist. North of Denny Way, the only way to cross the limited-access highway was via the underpass at Mercer Street. But one of the silver linings of SR-99 tunnel project that the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) is wrapping up is a reclamation of that stretch of urban roadway south of the ramps that have been added at Harrison Street.

Last year, a crosswalk was added at Harrison, the first of three new signals between Denny Way and SR-99 that repair the street grid. This segment of Aurora was renamed 7th Ave N to signal that return. And just last month, a signal at Thomas Street was turned on. But anyone hoping for a full departure away from the freeway-centric design of the past will be sorely disappointed.

When all of the work on 7th Ave N from Denny Way to Harrison Street is complete, it will be a massive road: two general purpose lanes in each direction, a center median, left turn pockets, and right turn lanes. Where the right lanes aren’t needed as turn lanes, they will be transit-only lanes. A brand new seven-lane road is opening in the middle of Seattle’s fastest-growing neighborhoods. And yet somehow there isn’t enough room for full transit priority on the street.

WSDOT’s SR-99 design funnels traffic exiting and entering Aurora Avenue N but not utilizing the deep bore tunnel (including all King County Metro buses) onto one single lane on the Harrison Street ramps. There are southbound bus lanes on Aurora Avenue N, but there is no direct bus-only connection to 7th Ave N. In fact, southbound buses don’t just lose their bus lane, but also must merge left across two lanes of traffic to reach the left exit. Mike Lindblom at The Seattle Times reported this fact from the WSDOT plans for SR-99 many years before the corridor was complete, but no fix was ever implemented.

One lane to enter and one lane to exit SR-99 from Harrison Street and yet WSDOT has designed 7th Ave N to have seven lanes of traffic?

The new 7th Ave N will have dedicated space for buses, but only in areas where there are no right turn lanes needed. At intersections, the transit-only lane will double as a turn lane, delaying a bus full of riders if one car is turning or requiring the operator of the bus to move into the general purpose lane. Unnecessary lane changes lead to more collisions.

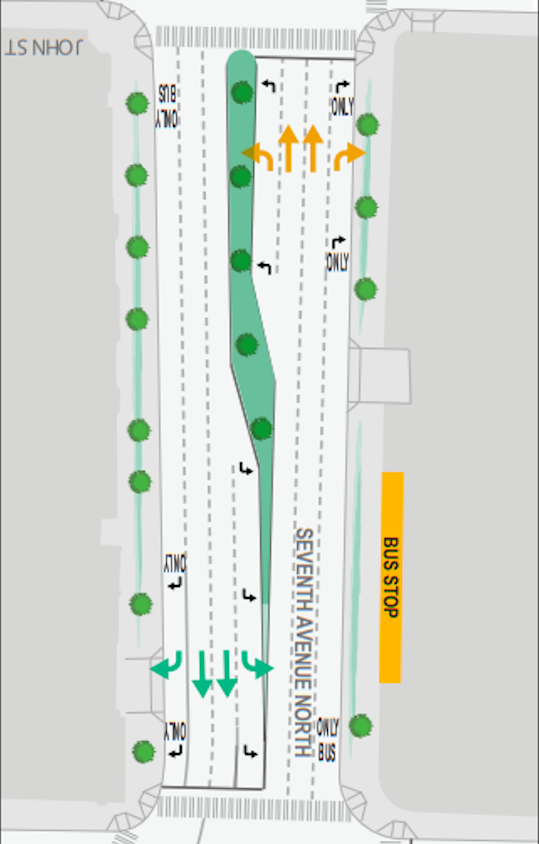

In the first block of 7th Ave N heading north from Denny, as shown below, the only dedicated transit space is the area in front of the northbound bus stop northbound, and directly south of John Street southbound.

A bus stop that used to drop riders off on Aurora just north of Denny Way southbound is not returning to the new 7th Ave B. Directly south of Denny, the transit-only lane reappears and runs to the nearest southbound stop for buses using the corridor, on Wall Street.

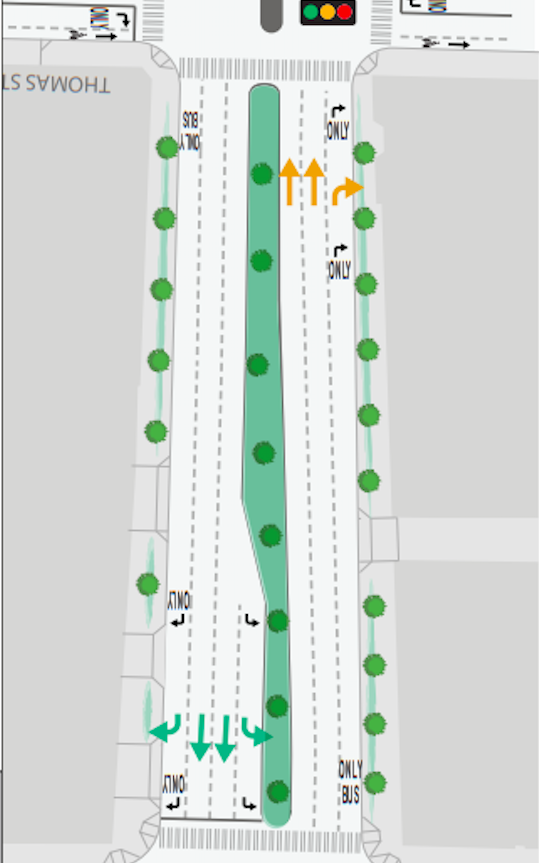

Looking at the next block of 7th Ave N heading north, between John Street and Thomas Street, there are no bus stops in either direction. There isn’t a need for buses to be near the curbs, yet there is no dedicated transit space apart from a short segment immediately after the intersections on this block either.

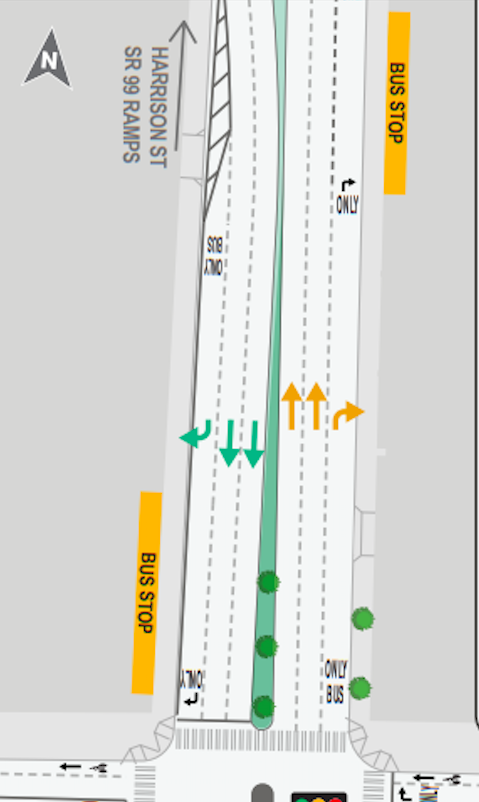

The same goes for the final block before the Harrison Street pinch point. Here WSDOT’s graphics actually show the bus stops for both northbound and southbound buses in the middle of the right turn lanes themselves.

The buses that use this corridor include the E Line (the busiest route in the entire King County Metro system), the 5 and 5X, 26X, and 28X. Together these routes averaged more than 31,000 daily riders every weekday, more people than use Westlake, Capitol Hill and University of Washington Link light rail stations combined. King County Metro’s 2019 system evaluation report notes that every single one of those routes are late during the afternoon peak period more than 20% of the time.

Northbound buses do have the benefit of using a short bus-only queue jump immediately north of Harrison Street, which they will access after changing lanes to get around any vehicles turning right (or waiting for them to turn).

There is no clear need whatsoever for 7th Ave N to have two lanes in each direction. Harrison Street’s ramps onto SR-99 only have one. Once the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) gets control of this stretch of street, they should immediately restripe the entirety of the corridor to prioritize transit.

Right turns do not have to be permitted at every single intersection along 7th Ave N. The street functioned for decades with no access provided for people on foot, and yet the new design provides for separate turn lanes for every single intersection. Transit lanes on Westlake Avenue, by comparison, do include turn restrictions at certain intersections to prevent the bus lane from being blocked by turning vehicles. This would make the most sense at the Thomas Street intersection, which is being re-envisioned as a corridor for walking and biking. Diverters will force drivers onto alternate routes: turns could be prohibited from 7th Ave N as well to speed up transit.

How did this happen? The environmental impact statement for the entire Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement project doesn’t spend much time talking about the fate of 7th Ave N, though when it does, it sounds mostly positive: “The neighborhood would no longer be divided by SR-99, and vehicle, bicycle, and pedestrian circulation would be enhanced.” However, it also adds: “This would not change the visual quality of the street, which would continue to be a six-lane urban arterial. The major difference would be the slower speed of traffic and the periodic queuing of cars at intersections.” Apparently nothing was in place to ensure that WSDOT didn’t just do what it does best: jam as much general purpose roadway capacity anywhere it can.

An overbuilt 7th Ave N is also paired with an overbuilt 6th Ave N that’s already open. 6th Ave N is the designated corridor for drivers accessing SR-99 on Denny Way from the west. Here another four lanes of traffic funnel vehicles to and from the Harrison Street ramps as well. The misallocation of road space is so gratuitous it should be embarassing.

The Washington State Department of Transportation’s designs for this brand new street in the middle of Seattle of are so out-of-sync with Seattle’s transportation needs that they never should have seen the light of day. Quick fixes might be the best option at this point, but it’s very clear that our state transportation agency is still the department of highways.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.