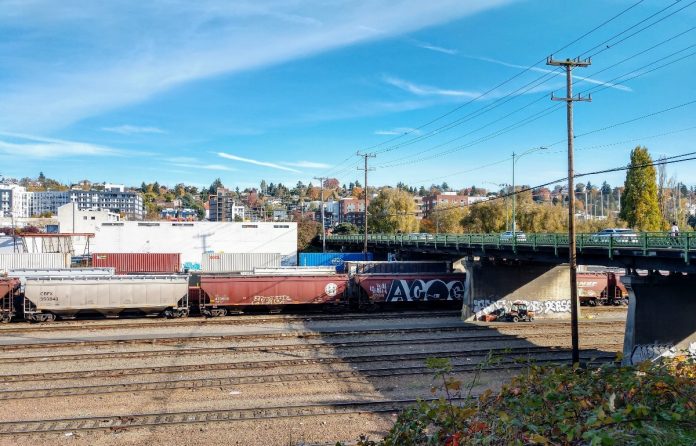

Interbay is a collision of changing urban landscapes, expensive deteriorating infrastructure, and confused layers of authority. As the smaller of Seattle’s two industrial centers, Interbay is ground zero for the conflicts of a city that is changing from the great Yukon supply hub to the digital service economy. For the last decade, the Interbay area has added more mini-storage units and residential apartments than it has fishing berths or warehouse capacity.

Over all of this fluctuation, there has been one constant. The industrial land in Interbay, Ballard, and along Commodore Way to the northwest have been subject to a single, unchanged plan called the Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Center (BINMIC). The 20-year Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Center was approved in 1998 with the stated goal “to ensure that adequate accessible industrial land is available to promote a diversified employment base and sustain Seattle’s contribution to regional high-wage job growth.”

The plan has failed. Its underlying assumptions are no longer viable, the many basis for its proposals changed, and its sunset passed. But since no new plan has replaced it and several parallel processes have referenced it, the BINMIC remains in place like the rusting hulk of a derelict boat polluting the Ship Canal.

A Once Proud Plan

In the late 1990’s, BINMIC and its Environmental Impact Statement were the test cases for planning under the newly approved Growth Management Act. Lauded as progressive at the time, the BINMIC established many of the processes that have been used elsewhere in the region to establish centers for growth.

The 30-person committee that created the plan was comprised of industrial business owners, chamber of commerce reps, the Port and BNSF Railway. The plan’s six sections include policy and action items categorized as economic development, land use, maritime & fishing, public services & infrastructure, and regulation with the largest number of recommendations devoted to Freight Mobility and Transportation.

Terrence Danysh was on the Seattle Planning Commission during the 1990’s when many plans like BINMIC were kicked off. He is now with Dorsey & Whitney LLP as principal counsel for land use and regulatory projects throughout Washington. In his perspective, plans like the BINMIC are not one-time shots. “The authority of the Growth Management Act comes from plans that are updated regularly.”

Unfortunately, change has been a true constant in the BINMIC area.

The Carcass of a Plan

It is in the BINMIC mobility recommendations that we start to see where the plan is no longer applicable. The biggest and most detailed of the sections, Freight Mobility and Transportation outlines 40 recommendations covering everything from intersection improvements to bridge rehabilitations to carpool programs. Many were never implemented.

There are a lot of recommendations about Leary Way, sensible as the primary arterial for businesses on the north side of the Ship Canal. Recommendation T-5 proposes improvements to move traffic from impacted Shilshole Avenue onto free flowing Leary Way. Recommendation T-6 proposed development of Traffic Signal Interconnect for the eight lights along Leary between 15th Avenue and the Fremont Bridge to time the lights for smooth traffic flow. Recommendation T-16 proposes a traffic signal at Leary Way and NW 46th Street.

The problem is that there are now three pedestrian signals on Leary between 15th and Market, and another twelve traffic signals along Leary between 15th to the Fremont Bridge. Almost the only intersection on this road to not get a traffic light was the proposed one at NW 46th Street. In the 22 years since the BINMIC was approved, our goals with traffic have changed. Pedestrian safety and slower traffic speeds have become priorities. We rarely create free-flowing de-facto highways in residential neighborhoods anymore.

There are a lot of places in the plan just like this. Recommendation T-4 proposed 16 directional signs to move freight from I-5 and SR99 to the BINMIC and back. Less than half were installed. The ones proposed for Broad Street and the SR-99 Viaduct cannot be installed because the roads no longer exist. Recommendation T-14 proposes locations for non-arterial pavement maintenance in places like NW 42nd Street between Leary and the Ship Canal or 26th Avenue south of Market. Some of this has been implemented, such as curbs and asphalt on 11th Avenue. But it was installed as part of a commercial development, the antithesis of what BINMIC was trying to do.

Time has overtaken the BINMIC assumptions. The BINMIC’s top line economic development policies featured the addition of 3,800 new jobs over the existing 14,000 by 2014. By 2010, the area had actually lost 400 jobs. By 2017, industrial jobs were down to 10,000 and service jobs in the area were up to 22,000.

Moreover, the plan’s omissions are stark. There is no reference to climate change. There is passing reference to earthquakes and nothing about liquefaction. There is only one reference to an urban village–the planning designation that has put thousands of new homes in Ballard. BINMIC only brings it up as a discussion of automobile mobility and nothing about the coming transit or light rail that will connect it.

Why Zombie Plans Matter

It sounds wonkish or deep planning nerd to worry about a document that’s two years out of date and hasn’t been implemented.

However, the BINMIC is regularly drug out for community input sessions in a wide variety of circumstances. It was referenced in the continuing fight about the Missing Link of the Burke Gilman Trail. It came up in opposition to residential uses in Interbay and as support for complete replacement of the Magnolia Bridge.

That’s the damage that Zombie Plans can do. Not only are they out of date, but they are shored up by other documents. Although two years past its end, the BINMIC is referenced in the Seattle Comprehensive Plan as well as the Puget Sound Regional Council’s Vision 2050. These newer plans are in effect, and by reference help the empty BINMIC husk shamble into the future. It’s left to another round of community groups to argue that the BINMIC is out of date.

Mr. Danysh emphasizes the “fundamental imbalance” of requiring neighborhoods to provide evidence that a plan is outdated or its assumptions are wrong. “It is a challenge for non-funded groups to attack a problem that has funds and can hire experts.” The BINMIC may no longer be detailed enough, but to demonstrate that its underlying assumptions are outdated requires cash.

The BINMIC even includes an illustration of what a privileged community can get. On page 26, the plan references the 1985 Short Fill Agreement between the Port and Magnolia Community Club and the Queen Anne Community Council. The agreement put to an end lawsuits about port uses and gate access at Terminal 91. This 35-year-old agreement continues to dictate the development and relationship between a state authority and two wealthy neighborhoods. Not only is the BINMIC a zombie plan supported by others, it also has codified this Short-Fill agreement into a second generation.

Industrial Red Herring

Industrial development is some of the most expensive investments undertaken by corporations and cities. Our major water, rail, and highway arterials are built to support commerce and freight. Separating industrial uses is the basis of zoning. It is the definition of sunk costs. Industrial investment is the reason we have a stock market and a barometer for how well or poorly it’s doing.

But that is not the development that is actually occurring in Interbay, regardless of the design. And this conflict of everything against industry is nothing new. Mr. Danysh observes that the city “for years stressed industry and not sacrificing businesses. But the BINMIC needs reconciliation instead of drawing battle lines.” Arguing about just industrial uses keeps us from being able to tackle the other pressing problems in the neighborhood.

So, this is not an argument to shelve our aspirations of keeping industrial jobs in the city or protecting working waterfront uses. This is a call to be realistic about the limits of our plans. If a plan does not work, is not working, and has not worked, it’s our job to recognize that. Dragging along the carcass of a failed plan does real harm to the health of the city by impairing the function of institutions that manage growth and by overwhelming neighborhoods and infrastructure that have prepared for growth.

It’s time to recognize that the BINMIC is dead. Long live Industrial Seattle.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.