Last week, news broke that a King County payroll tax is in the works. Seventeen Democratic state representatives have signed on a bill (House Bill 2907) that would give King County the authority to institute a payroll tax of up to 0.2% on firms employing workers making $150,000 or more annually–with some exemptions. King County Executive Dow Constantine and Mayor Jenny Durkan hailed the effort, and backers hinted of major business support.

It turns out business leaders are conditioning their support on a litany of demands–the biggest being that the State Legislature would block Seattle from adding more business taxes. The Downtown Seattle Association released a letter listing more than a dozen demands. They also insist that payroll tax revenues are spent via the recently launched Regional Homelessness Authority rather than by the City of Seattle. That would require a revision since the current language grants the City of Seattle 43% of proceeds given the geographic incidence of the tax being similar.

Mayor Durkan declined to take a position on Seattle tax preemption. Preemption would seem to go against local leaders’ pledges to end homelessness and addressing the housing affordability crisis since it would block one of the clearest paths to raising enough money to do so. Katie Wilson, General Secretary of Seattle Transit Riders Union, laid out the case against preempting Seattle’s tax authority better than I could in her Crosscut op-ed.

“This is a textbook case of the powers that be making a small concession to avoid a larger one,” Wilson wrote. “Anyone who cares about truly righting our upside-down tax system and building affordable housing at scale should vigorously oppose preemption. Seattle has precious little progressive tax authority as it is. It’s irresponsible to bargain what we do have away–especially when the grand prize is a county payroll tax that tops out at 0.2%. (Move that decimal point over to 2% and then let’s talk!)”

Solving homelessness

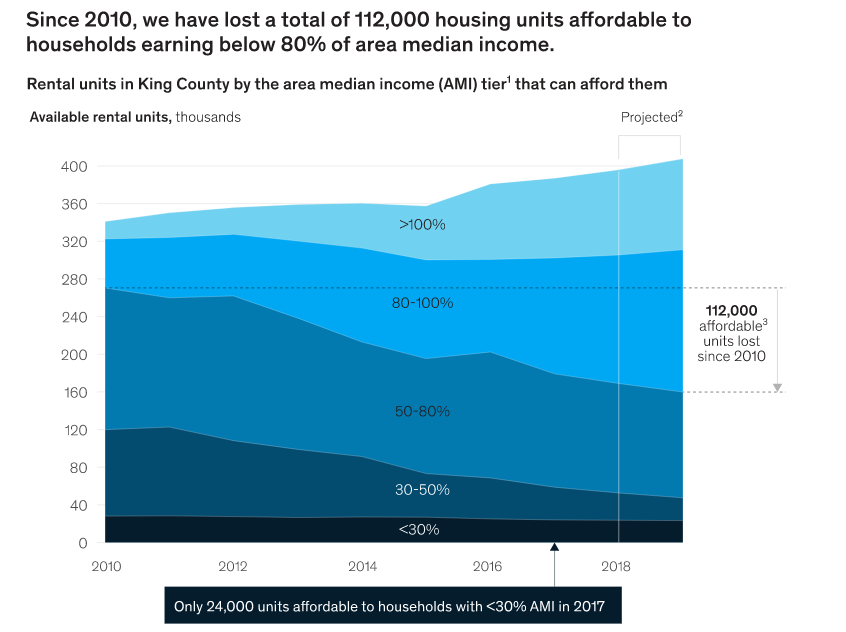

High-powered business consultants McKinsey & Company estimated the need as much greater than the $120 million per year the county payroll tax is designed to raise. In a recent McKinsesy report, consultants Benjamin Maritz and Dilip Wagle estimated the cost would run into the billions just to solve King County’s housing gap for extremely low-income households–defined as those making 30% of area median income.

“Using a conservative set of assumptions, ending the homelessness crisis in King County would therefore cost between $4.5 billion and $11 billion over ten years, or between $450 million and $1.1 billion each year for the next ten years,” they wrote. Again that’s the estimate just to house the population segment making less than 30% of area median income.

The broader affordable housing crisis

Solving the housing crisis up to 80% of area median income would take even more investment, as would the middle-income segment from 80% to 120% of area median income, where household budgets are still stretched and housing options limited. Mayor Durkan recently released a report from her Affordable Middle-Income Housing Advisory Committee with recommendations for that income bracket.

McKinsey arrived at the $4.5 billion to $11 billion figure by estimating between 15,700 and 37,000 new homes are needed for extremely low-income households at an average cost per home at $325,000. Meanwhile, King County’s Affordable Housing Task Force has estimated 156,000 new homes are needed currently with another 88,000 by 2040 to solve the affordable housing shortage up to 80% of area median income. Building 244,000 homes would take a $79 billion investment assuming each home costs $325,000. King County wouldn’t need to single-handedly take on this investment, but federal housing investment hasn’t been at that scale in recent memory, and the philantropic community has never attempted building on such a massive scale. Thus, King County might not want to count on huge amounts of outside assistance.

King County has ample resources for the taxing

King County is an economic powerhouse. With a population of 2.25 million, King County has a gross domestic product (GDP) of nearly $300 billion and is among the fastest growing in America. In fact, King County’s GDP is greater than Oregon’s or South Carolina’s. Employees making more than $150,000 account for $61 billion in annual compensation and those 185,000 high-salaried employees make about 44% of all compensation in King County, according to the Mayor’s office.

Though commonly called a payroll tax, the proposed tax technically is as an excise tax on companies paying those $61 billion in top salaries. Given those incredible resources, 0.2% isn’t a big tax hit, especially with the exemptions included for more vulnerable businesses. Wilson’s call to increase the allowed tax rate rings true. And 2019 election results–in which business-backed candidates mostly got shellacked–suggest voters agree and that raising progressive revenue for affordable housing is popular.

Capping King County’s additional investment in housing at $121 million per year might make sense to the corporate bottomline, but it makes very little sense from a policy perspective, especially applying an equity lens. As Xochitl Maykovich, political director of Washington Community Action Network, put it in a tweet: “How can the @downtownseattle claim to prioritize lived experience and anti-racism if they–largely white men who are rich–are dictating the spending?”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.