With Willowcrest Townhomes, Homestead Community Land Trust is striving to create “a replicable model” for permanently affordable net zero energy housing.

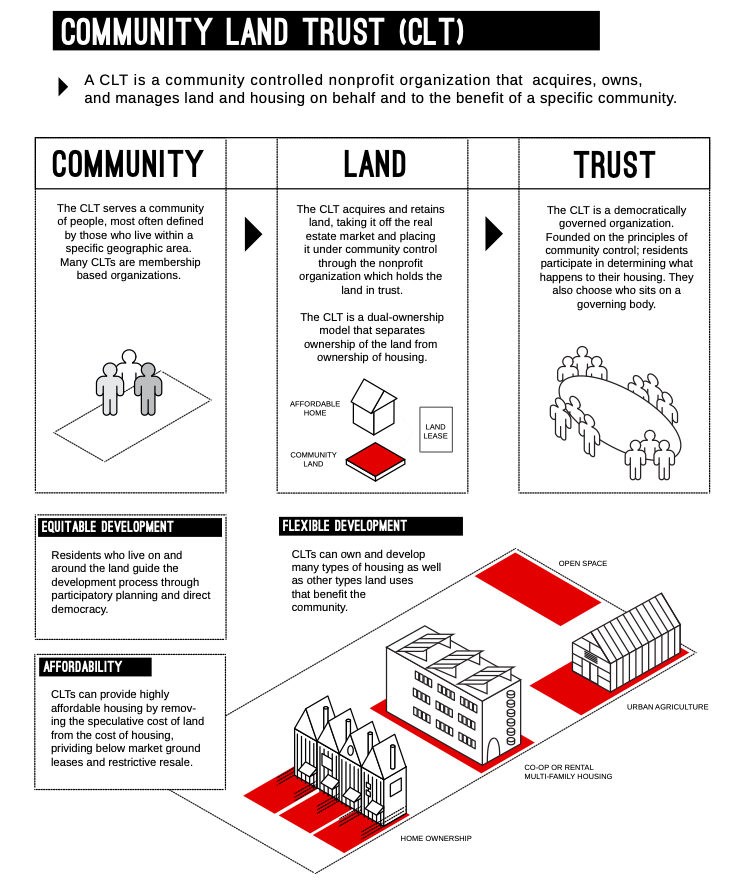

Since the 1960s, community land trusts have been among the most successful affordable housing models in the United States, and in the wake of the current nationwide housing affordability crisis, they’ve gained renewed attention. Since community land trusts create permanently affordable community-owned housing, they’re seen as a particularly effective tool in the fight against gentrification and displacement of low-income residents.

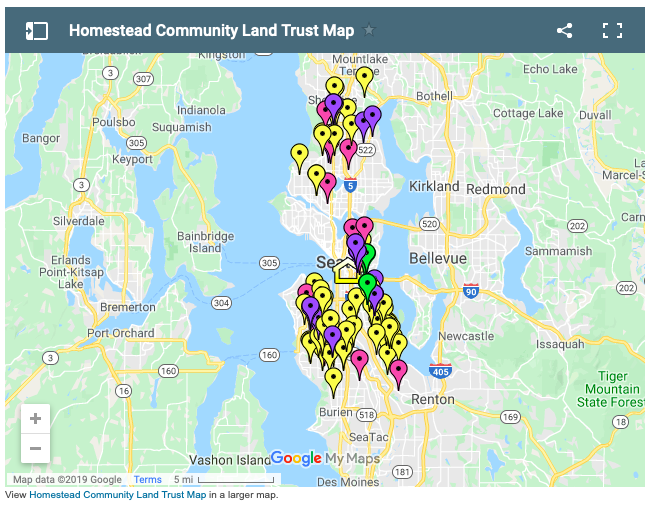

Puget Sound-based Homestead Community Land Trust (CLT), which was first incorporated in 1992 by low-income residents of the Central District and South Seattle, currently holds over 200 permanently affordable homes in trust, making Homestead one of the largest CLTs in the Pacific Northwest.

CLTs offer permanently affordable housing by controlling the resale price of homes with the trust. At the time of purchase, future homeowners are provided information on the what the terms of the investment are, including ground lease provisions and limitations on accrual of equity. In the case of Homestead, buyers can expect to accrue 1.5% equity in their home, which is compounded annually. While buyers must meet income requirements at the time of purchase, buyers are not obligated to sell their home if their income increases after purchase.

“Our formula for equity is designed to balance two competing goods,” said Kathleen Hosfeld, Executive Director of Homestead CLT. “We want homeowners to build wealth, but we don’t want the property to become unaffordable for the next low-income home buyer.”

In addition to capping resale value, Homestead CLT also requires that buyer use the homes as their primary residence, with some short-term rental exceptions.

As displacement of low- and moderate-income households has increased in recent years throughout the Seattle-area, Homestead has targeted its affordable housing development efforts for neighborhoods at risk of displacement. A map of Homestead’s current properties shows its single family residences, condos, and townhomes are mostly located in Seattle, especially in the city’s Southend.

Working toward social and environmental justice

From the beginning some CLTs have been created to serve both social and environmental justice objectives. In fact, the first CLT established in the United States, New Communities in Lee County, Georgia, was created by Black farmers seeking to preserve their agricultural way of life and increase wealth building through community ownership. Although New Communities was nearly shut down in the 1980’s after racist lending practices denied emergency loans to the organization during a severe drought, New Communities eventually persevered in winning a decade-long class action lawsuit and it still exists today as a regional center for social justice education, new agricultural techniques, wildlife preservation, engagement with the restorative landscape through low impact activities like hiking and biking.

In keeping with this environment justice legacy, Homestead CLT recently broke ground on its most ambitious project yet, Willowcrest Townhomes, King County’s first multi-unit homeownership project designed to be affordable to low-and moderate-income households while also reducing utilities costs and climate impacts through ultra-high energy efficiency and the elimination of fossil fuels.

Built on land provided by the Renton Housing Authority in northeast Renton a stone’s throw from the Renton Highlands Library, the 12 three-and four-bedroom townhomes will achieve net zero energy usage through highly energy-efficient systems and construction and the use of solar panels for onsite energy generation.

All of this will come at a price of less than $315,000 for buyers who qualify as low or moderately low according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) criteria for the King County area.

The “largest ever” affordable housing grant from the City of Renton, a $332,000 that help pay for some of the energy efficiency and green-building features of the project, as well as a $500,000 investment from King County’s Transit Oriented Development fund, which promotes housing development in proximity to high-capacity public transit services, were both critical subsidies that helped make Willowcrest Townhomes a reality. King County Executive Dow Constantine described Willowcrest Townhomes as “leading example” of how it is possible to achieve equity, mobility, and sustainability goals while creating new housing.

While Homestead CLT currently has a similar project in works in Tukwila, Hosfeld’s intention is for this work to go on to have an even bigger impact.

“Our hope is to create a replicable model and build the case for philanthropic and public investment in deeper green building standards for affordable homeownership in King County,” said Hosfeld.

What makes Willowcrest Townhomes a replicable model?

One of the most interesting features of the Willowcrest Townhomes development is that the project has been designed to be copied and shared.

During our conversation, Hosfeld pointed some of the criteria which she feels make Willowcrest uniquely scalable. Not only have the homes been designed for energy efficiency, the layout and specifications of the homes has been been designed for future replication. Homestead CLT aims to share what they have learned about designing for energy efficiency with affordable housing colleagues across the Pacific Northwest and other similar climates. “We want to keep repeating the same design plans,” Hosfeld said. “The more we can do that, the more efficient we can become. Each new development offers the opportunity to learn and improve.”

Changing perspectives on what to prioritize when building affordable housing is another goal. “For too long people have framed the affordability and sustainability criteria as competing with each other. Either/or framing is the wrong way to think about it. It’s important to recognize the interdependence between human welfare and the natural environment,” Hosfeld said. “We need to focus on commonalities and shared need. When we reduce utility cost through net zero energy, those homes become more affordable. When we build homes with low VOC [volatile organic compounds] we reduce health risks for homeowners.”

But Hosfeld also acknowledges that sustainable features can increase housing cost. The question, Hosfeld argues is not whether or not sustainability should be integrated into affordable housing development, but instead how much is too much? “There is a point of diminishing returns,” Hosfeld admits, “and we don’t know what the sweet spot is yet.”

While housing conversions may appear to offer cost benefits over the development of new housing, Hosfeld clarified that new construction is actually easier, faster, and more affordable because of the larger investments that the process of converting existing buildings can require.

In order to grow to scale, CLTs need greater municipal and philanthropic support

Hosfeld said that while housing wonks like the Sightline Institute have recognized the promise and potential of CLTs for years, it has taken longer for local municipalities to get on board. Hosfeld attributes this hesitance in part to the fact that it can be difficult for cities like Seattle to recognize that the housing challenges people face are not the result of a temporary crisis. But in the wake the the current housing affordability crisis, Hosfeld has noticed a change. “[City officials] have started to realize that we need a solution that will serve more than one generation, and this model addresses the issue permanently,” she said.

Another challenge is the fact that public funds for affordable housing are often allocated to housing development for people with the lowest incomes, while CLT projects currently serve low- to moderate-income individuals and families.

Hosfeld believes part of her work is to advocate to politicians about the importance of affordable ownership housing as means to stop the hollowing out of the middle class and the disproportionate impact that has on lower income households in the 50-80% area median income (AMI) range.

“A positive, upward, transformational power is introduced when households get to stabilize in place with an affordable mortgage. It benefits homeowners emotionally, physically and economically and sets in motion a lot of positive life mobility,” Hosfeld said.

Philanthropic support from the private sector is another area that Hosfeld would like to see grow in the coming years. Recent large pledges of funds for affordable housing, like Microsoft’s declaration it would loan $500 million to support affordable housing development in the Eastside of King County and the Puget Sound region, won’t be used to support the development of CLT projects. But with demand for affordable homeownership already at record heights, large scale donors interested in supporting permanently affordable housing solutions might start to catch on to what CLT’s offering.

While Homestead CLT has not selected the homeowners for the 12 Willowcrest Townhomes, competition is sure to be steep. More than 800 qualified households are currently registered on Homestead CLT’s waiting list.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.