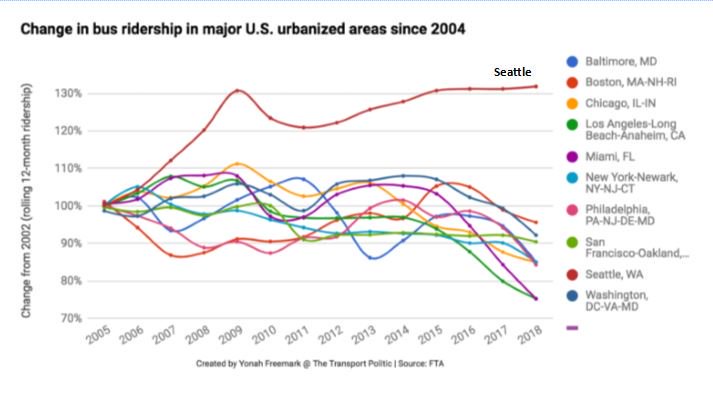

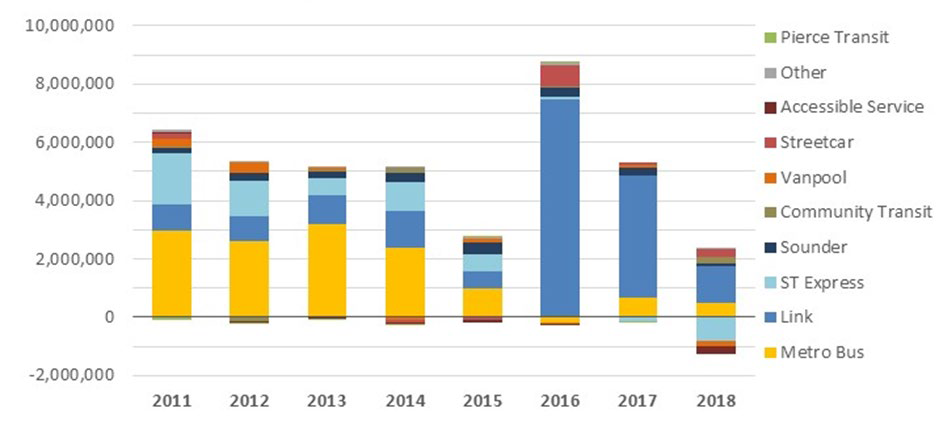

Seattle’s remarkable run of transit ridership growth appears to finally have hit a speed bump. King County Metro’s ridership grew at its slowest pace in years in 2018, and Link light rail ridership was down slightly last quarter. In previous years, the region had bucked national trends, growing steadily as many other agencies bled riders.

The reasons that transit ridership grows or shrinks are complex and involve an interplay of many factors–including population shifts and construction impacts–but Metro said that the ridehailing industry is having an impact.

“Since 2015, local Uber and Lyft rides have increased from 27,000 rides a day to 91,000 rides a day in 2018 (equivalent to 22% of weekday Metro bus ridership in 2018),” Metro spokesperson Torie Rynning said in an email. “Studies in other cities have been able to more definitively link declining transit ridership to the increase in ride-hailing trips.”

Lower gas prices and the increase of teleworking and flexible work arrangements may also be contributing to slowing ridership growth, Rynning said. Nonetheless, Metro emphasized the long-term trend is steady growth.

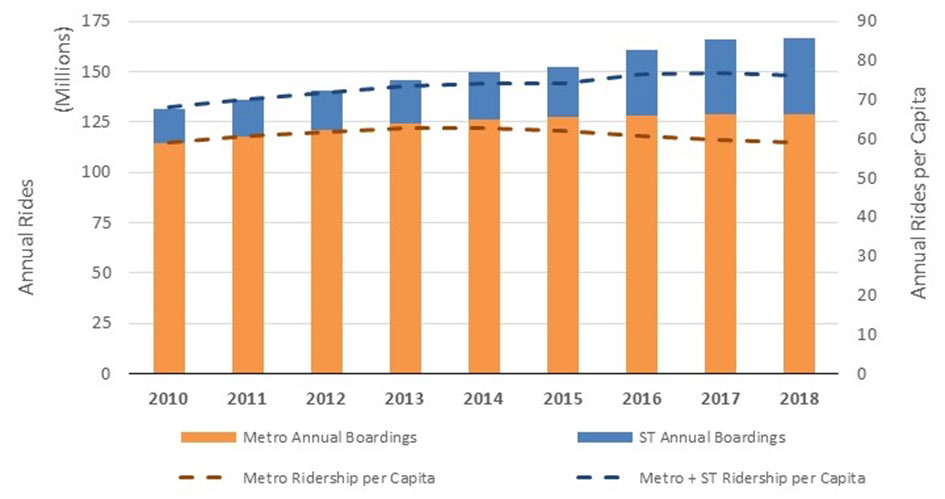

“Over the last decade, Metro system-wide ridership has grown from 113 million boardings in 2010 to almost 127 million boardings in 2018,” Rynning said. “While ridership remains steady, it has increased at a slower pace since 2015.”

Macro-level factors like employment growth, demographic shifts, and denser growth patterns are still in transit’s favor and likely to outweigh short-term disruptions like construction and a ridehailing boom that may be a bit of a fad–unless ridehailing giants currently losing billions starts turning a profit for investors. Moreover, local governments can take actions to proactively guide transit growth. Metro identified transit priority–things like bus lanes and queue jumps–as a key to future success.

“Metro can’t do it alone, and a crucial part to growing ridership involves working with Seattle and other partner cities to provide transit priority by making speed and reliability improvements within the right-of-way to keep buses moving as congestion increases,” Rynning said. “Metro also needs more employer partners to get more ORCA cards in their employees’ hands as a workplace benefit and to encourage the use of transit for their commutes.”

As luck would have it, the Seattle Transit Riders Union has an “ORCA 4 All” campaign that would do just that, and it appears to have support in the Seattle City Council. The initiative proposes requiring large employers subsidize ORCA transit passes for all their workers.

Transit priority and transit camera enforcement is made essential by worsening congestion driven by a booming economy and a booming population. Previewing an annual traffic report due out soon, City Traffic Engineer Dongho Chang confirmed that traffic levels on city streets had increased in 2018, reversing a downward trend in years previous. Although a slowdown in hiring at Amazon and other major employers means Seattle’s population didn’t grow quite as fast as in previous years, it’s still growing steadily. Seattle topped 750,000 residents this year. King County’s population hit 2,226,300 in April, the State estimated–that’s up more than 200,000 since 2014.

A larger populace should translate into higher transit ridership–unless a dip in transit mode share offsets the population gain. Annual transit trips per capita went down ever so slightly in 2018. King County could cross a tipping point where population gain isn’t enough to offset fewer trips per person, meaning a dip in annual ridership.

For Metro’s purposes, where population growth is occurring is important. Seattle Transit Blog‘s Dan Ryan proposed that the suburbanization of poverty and of working class households was largely to blame for the transit ridership lull in his Monday article.

“Much of the county’s recent growth has occurred in dense urban centers, which are well served by transit but also where Uber and Lyft rides are concentrated,” Rynning said. “In addition, this development pattern has enabled an increase in walking to work along with transit, as noted in a recent Seattle Times article. At the same time, more low-income households in the county are living in suburban areas that are less well-served by transit and where it is more difficult for transit and other modes to compete with single occupancy vehicles.”

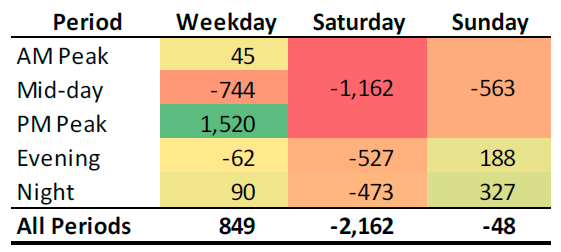

The timing of Metro’s ridership losses supports the hypothesis that Uber and Lyft are cannibalizing ridership. Afternoon peak ridership continues to grow steadily and morning peak saw a slight uptick, but Metro is hemorrhaging riders mid-day and on Saturdays. This is despite significant service boosts in these time slots.

The Seattle Transportation Benefit District supplements Metro’s total countywide service levels by a whopping 8%, but Metro’s bus base pinch means that it’s operating essentially at capacity during peak hours, pushing added hours to off-peak when they have spare buses. Off-peak service boosts haven’t stemmed ridership losses, though. Many people likely view ridehailing or driving as more convenient when congestion lets up off peak and bus frequencies–even with added trips–remain significantly lower than at peak times.

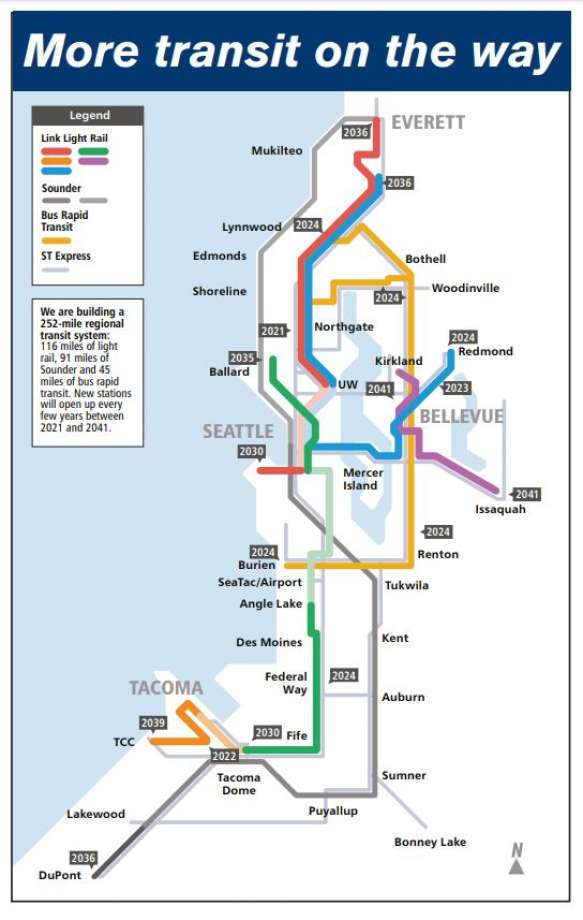

As the Seattle metropolitan area continues to grow, traffic congestion is likely to worsen. Infrastructure projects inevitably bring pain before they bring relief as construction work disrupts traffic flow. The opening of East Link, Federal Way Link, and Lynnwood Link remains the light at the end of the Seattle Squeeze tunnel, but in the interim, kicking buses out of the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel (to facilitate construction and that greater light rail capacity in the tunnel) has made commutes worse for many bus riders.

Some major infrastructure projects–notably the Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Tunnel–were never geared toward transit in the first place and may hinder it going forward. The four-billion-dollar project didn’t just fail to add bus lanes, it also forced West Seattle buses to use a traffic-clogged city streets–at least until the new Alaskan Way Boulevard opens in a few years. On the north end, the redesigned SR-99 interchange forced Aurora buses to merge across two lanes of traffic from the relative comfort of bus lanes on the right side of the highway to a left-hand exit plagued with traffic backups as the road approaches Denny Way.

“Routes directly affected by [Viaduct-related] changes have realized slower travel times and decreases in ridership between spring 2018 and fall 2019,” Rynning said.

Slights like these frustrate bus riders and may well be the reason some are riding less or have given up on their bus commute. Even though Seattle has boosted service off-peak, transit ridership has dropped in that time frame. This is deeply troubling is it persists. Meanwhile, the Washington State Department of Transportation launched a media blitz (larger than any ride transit campaign ever attempted in this state) to convert people to car commuters in order to fill its new tunnel.

But this isn’t the end of the story. To grow ridership at a faster pace, Metro, via its spokesperson, pointed to four projects:

- Expanding the frequent transit network as envisioned in the Metro Connects long-range plan;

- “Expanding our bus base capacity to provide more bus service in the peak periods with the most demand;”

- Smart bus restructures that “consolidating stops to provide better connections, improve speed, and enhance frequency of key routes;” and

- Innovative Mobility pilot programs to develop new services to address changing customer needs.

Rynning pointed to Via to Transit as a promising pilot program, and Metro did report it was attracting much higher ridership than the floundering Ride2 pilot that was axed this month. Via to Transit partners with the ridehailing provider Via to provide on-demand rides to Link light rail stations in Southeast Seattle and Tukwila. Arguably, partnering with a ridehailing company is a ‘if you can’t beat them, join them’ solution. However, Via’s approach is unique in that it’s collaborating with a local transit agency rather than seeking to disrupt it and poach riders unwillingly. Perhaps this kind of partnership offers a way out of an otherwise predatory arrangement. In April, the one-year Via to Transit pilot will end, and we’ll find out if Metro is extending the program.

Seattle’s 51-cent increase to the ridehailing tax represents a step forward in recognizing the social costs of an extractive industry, and it will help boost transit funding and offer some protections to exploited drivers. However, more actions are needed to promote transit and discourage driving. Congestion pricing would greatly change the equation, but it appears to be appear a few years off at best, with a decent chance of being a political quagmire.

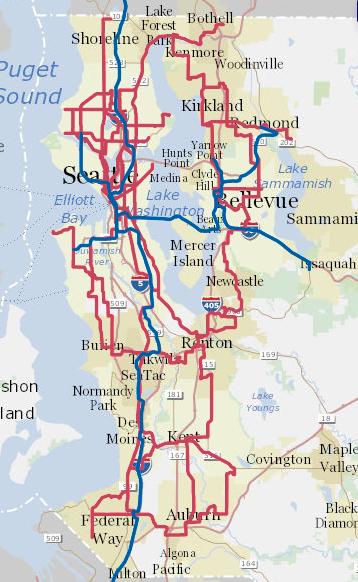

The Move All Seattle Sustainably (MASS) coalition has pushed the City to add bus lanes, particularly on the most heavily used routes. We suggested these nine high-impact bus lanes as a starting place, but the passage of Initiative 976 has transportation agencies in a defensive mode–even though the courts appear poised to invalidate I-976 on constitutional grounds.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is planning to add Rainier Avenue bus lanes to speed Route 7 next year–although the section near I-90 won’t have them–and the newly-signed 2020 budget pledges 90 blocks worth of bus lanes overall. The agency has suggested this pace is about as fast as it can roll out bus lanes, but if we want to get transit ridership growing at a healthy clip again, we should probably find a way to add bus lanes even faster.

This article has been updated to note that Via to Transit pilot program ends in April, at which time Metro will make a decision on extending it.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.