What will it take to make congestion pricing a reality in Seattle?

Depending on whom you ask, road pricing is either just around the corner, far off on the horizon, or a pipe dream. One reason why it seems like a very tall order to pass congestion pricing–or decongestion pricing or a pollution surcharge as some prefer to call it to emphasize policy benefits of congestion relief and pollution reduction–is that some have contended that pricing would first need to go to a voter referendum before it could go into effect. That is Mayor Jenny Durkan’s plan as well. But, as far as I can tell, that interpretation of state law is incorrect.

Moreover, going to the ballot first may be a less strategic choice since cities rarely initiate road pricing as a referendum–going back to when Singapore pioneered the policy in 1975. On the other hand, some cities have defended pricing schemes against repeal referendums after residents see benefits of road pricing in action and realize the downsides are minor. I don’t know of any cities that have succeeded on the go-to-ballot-first route, and that puts Seattle’s plan on shaky foundation.

State law (Chapter 47.56 RCW) has laid out narrow guidelines for how state highways can be tolled, but these stipulations do not apply to local roads. Additionally, while transportation benefit districts (RCW 36.73.065) have to go to voters before they can toll, local governments do not have the same restrictions, except when tolling state highways and bridges (RCW 47.56.031).

The law is clear on this: “Similarly, local or quasi-local entities that retain the power to impose tolls may do so as long as the effect of those tolls on the state highway system is consistent with the policy guidelines detailed in chapter 122, Laws of 2008. If the imposition of tolls could have an impact on state facilities, the state tolling authority must review and approve such tolls,” RCW 47.56.805 states. In other words, Seattle doesn’t have to use a transportation benefit district to enact tolling, since local entities retain the power to impose tolls on local roads.

Mayor Durkan’s Plan

The Mayor’s Office should be commended for advancing road pricing, but I hope they revise their plan and implement pricing via direct legislation rather than referendum. It could be presented as a pilot program. That way road pricing has a chance to work–lessening traffic congestion, decreasing pollution, and speeding up transit–before it has to survive a popular vote.

I reached out to the Mayor’s Office for comment and a spokesperson said they were working under the assumption that state law required congestion tolling go to the ballot, but reaffirmed the Mayor’s commitment to working through the process.

“The Mayor is committed to moving forward with congestion pricing in a fair and equitable way, driven by the input received through a robust civic conversation,” said Chelsea Kellogg, spokesperson for Mayor Durkan. “This necessitates an intentional, responsive, and robust outreach and engagement process to identify a sustainable, progressive policy that can fund critical transit priorities, create a healthy downtown environment, and ultimately reduce the pollution that contributes to climate change.”

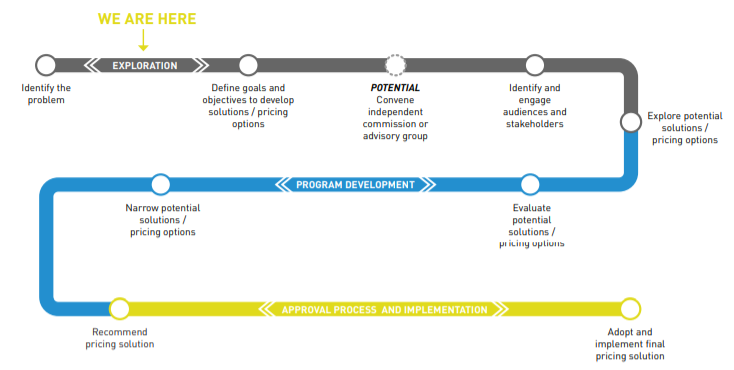

The Mayor has a community outreach plan and hopes to identify an equity mechanism through that process.

“In partnership with DON [the Department of Neighborhoods] and SDOT [Seattle Department of Transportation], OSE [the Office of Sustainability and Environment] is planning a series of workshops and community listening forums, in neighborhoods throughout the city, to better understand who is driving and why, while also capturing resident priorities and needs to ensure a future policy proposal does not burden those who are already most impacted by climate change and Washington’s regressive tax structure,” Kellogg added.

Outreach is a good idea, but it won’t necessarily swing public opinion on the matter. Putting controversial progressive policies on the ballot is certainly in vogue in Washington state right now, but that doesn’t mean it’s the right fit for road pricing. While it may seem politically safer to just let the voters decide, it brings its own complications.

The Ideal Time to Enact Road Pricing

Timing the initiative right is complicated. To face the most progressive electorate, an initiative should go on the ballot in a Presidential year, preferably a wave year, and November 2020 appears perfect on that front. The problem is that’s too soon logistically. 2020 is dedicated to outreach and policy formulation in the Mayor’s plan. The earliest feasible ballot date under that timeline is 2021, but that also runs into its own political problems.

First off, an odd-year will typically have a smaller and more conservative electorate. But it’d also require Mayor Durkan to fully run on congestion pricing since it’d be on the ballot alongside her. If she took that leap, that could be powerful, but it’s also incredibly risky and could backfire. One of her opponents is likely to run against pricing as an opportunistic way to contrast with the Mayor and grab a base in the primary. Given the skepticism around congestion pricing, that seems likely to work as a primary strategy, and, assuming it does, road pricing could be the defining issue of the 2021 mayoral election. Under this scenario, if Mayor Durkan loses, the new mayor would have come into office on a wave against road pricing probably delaying the policy by at least another four years through mayoral veto or indifference. 2026 would be the new optimistic launch date.

2022 is the other time road pricing backers are floating for a ballot initiative and that seems less fraught than 2021, but still problematic. The outcome of the 2021 mayoral election could still either invigorate the effort or take the wind out of its sails depending who wins. Will the winning candidate choose to distance herself from pricing while campaigning in order to either use it as a wedge issue or avoid it being used against her? It’s a Midterm year so turnout should be higher than an odd-year election but still well short of Presidential levels.

Fundamentally, no matter the year, the ballot-first route still asks voters to take a leap of faith on a policy they haven’t yet seen work, putting fear-mongering tactics in the driver’s seat.

The Benefits of Road Pricing in Action

That’s why I think the ideal way to pass road pricing is legislatively as a pilot project. Put it into effect in January so that it has several months to work before it has to withstand electoral politics and an inevitable repeal effort. Get out in front of criticism with a media blitz to highlight how:

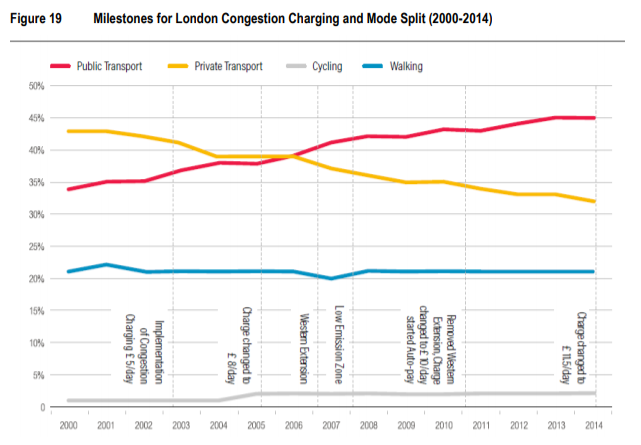

- Pollution levels are dropping. London saw a 12% decrease in nitrogen oxides and particulate matter within the toll zone. London and other cities have took to calling them “Low Emission Zones.”

- Public health is improving. Stockholm saw a 50% drop in asthma-related hospital visits after pricing.

- Congestion really is lower, making freight and carpooling more efficient. London has seen a 30% drop in congestion after pricing, while Singapore saw a 24% drop.

- Transit, biking, rolling, and walking are picking up the slack and thriving in unclogged streets. The London Congestion Charge has generated more than £1.6 billion to invest in transportation since 2003. Those investments and lower congestion have boosted transit and it helped London record its largest ever increase in cycling last year.

- Downtown streets are more pleasant places to get around. Cities with congestion pricing have been confident about closing streets to cars and creating pedestrian thoroughfares while Seattle still lets cars drive through Pike Place Market. Street cafes and downtown parks also perform better with less congestion, noise, and pollution.

- People are adjusting their commutes and liking their new options. People assume that commuters are set in their ways, but tolling really does impact their choices. Why should driving downtown be free when a bus fare is $2.75?

- Low-income people are getting rebates, exemptions, or free transit passes to lower the burden on them. This makes the policy’s impact even more equitable. Mayor Durkan and many pricing backers have been adamant that equity must be baked into the proposal. Whatever the mechanism, we’ll have to stress that it really is happening and helping low-income folks cope.

- Climate emissions are down. Congestion pricing helped Stockholm shrink its carbon footprint by 20%. Singapore estimated a 10% to 15% drop in carbon emissions from its congestion pricing system. Meanwhile, Seattle’s climate footprint keeps on growing.

We can show all these things if we pass road pricing via the Seattle City Council with the Mayor’s signature. The campaign to pass a ballot initiative would only be able to tell people these things. Seeing is believing.

During the pilot, the City should highlight that high-impact upgrades, such as bus lanes, are being backed by pollution fee revenue. Imagine putting bus lanes on a decongested Denny Way to suddenly turn the perpetually late Route 8, into a bus that people can rely on again. Imagine re-timing Mercer Street signals to prioritize people walking, rolling and riding buses so that routes like the 40, 62, and 70 face fewer delays crossing the Mercer Mess and are more dependable.

Stockholm legislatively enacted congestion pricing as a pilot program in January 2006 and then it faced a ballot referendum in September 2006. It passed in the City of Stockholm (though it failed in 14 surrounding suburban municipalities) because even in nine short months people had a chance to see it work. This is despite polling that hadn’t been favorable before they enacted the pilot program. Seeing it work sold residents on the program, convincing them to buy into supporting messages.

Perhaps my read of the state law is incorrect, but, even if it is, it may still be more prudent to lobby the state legislature to amend state law and clearly permit cities to implement road pricing rather than try the unproven strategy of passing a ballot referendum right off the bat. That could doom road pricing to years of delay and indecision.

The Seattle City Council isn’t exactly stacked with road pricing proponents–here’s how 2019 city council candidates answered our decongestion pricing question. However, convincing at least five councilmembers seems easier than trying to convince hundreds of thousands of Seattle voters to take a leap of faith–especially considering a campaign would have to out-organize the deep-pocketed automobile industry, which will spend liberally trying to convince voters of the opposite.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.