Interstate 5: It’s ugly, ubiquitous, and almost universally hated. It’s a wall that separates one side of Seattle from the other. It’s noisy and certainly not new. I-5 through downtown Seattle was finished in 1967. Fast forward over 50 years to the present day, and it’s fallen into a state of disrepair. The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) has been deferring I-5 maintenance for decades–road maintenance isn’t the shiny new project that gets politicians elected. At this day and age, a full rebuild is likely necessary if we want to keep I-5 like it is now.

But considering just how much money is on the table, sticking with the status quo and rebuilding the miles of I-5 suddenly seems less appealing. Perhaps we could spend our money on something else, something better than a freeway slicing through our city.

Something like we did with SR-99: burying the road into a tunnel and redeveloping the land where the road once stood.

And removing I-5 would be an absolute godsend for Seattle’s urban renewal. I-5 is a block wide–about as wide as the Central Library and the Columbia Center. Demolishing I-5 from SR-520 to I-90 would free up more than 50 blocks of land that could be redeveloped into much more useful things. A half-block parcel of land in the Denny Triangle recently fetched $60 million, meaning that an entire block of land could theoretically sell for $100 million apiece or more. (See also: the Mercer Megablock land sale.) Burying I-5 wouldn’t just be an urban awakening, it’d be a fiscal awakening.

The money would easily be put into the bored tunnel–something Seattle seems to love. Politicians in particular love a new grand project to brag about. Our city’s hilly terrain has made it the home to so many bored tunnels: the Link Light Rail tunnels under Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill, the Downtown Transit Tunnels, the Mount Baker tunnels… the list goes on. And the new I-5 tunnel could just be like the SR-99 tunnel we just built, meaning that we already have the research and development for the boring machine done. WSDOT could even take the lessons it learned the first time and apply them the second time around (e.g., don’t leave your metal pipe in after soil tests so that your contractor tries to blame you for its tunnel boring machine breaking down, delaying your project several years, and piling up cost overruns).

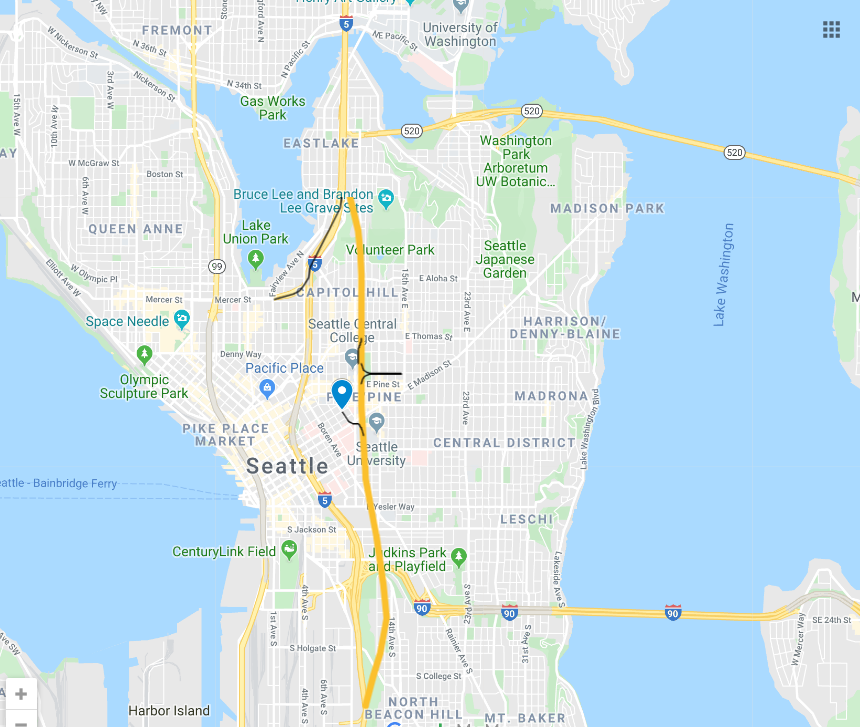

The new tunnel would be the same size as SR-99 (read: Bertha) and run from just south of the interchange with SR-520 to just south of the interchange with I-90. Taking into account the geography of our city, the tunnel would traverse Capitol Hill, dip down under S Dearborn Street, and then reappear somewhere near Beacon Avenue S, near where I-5 is right now.

At the northern and southern portals of the tunnel, I-5 would connect to expanded Eastlake Avenue and 4th Avenues. There could even be an exit somewhere near Madison Street, as the buildings on Capitol Hill aren’t nearly as tall as those in Downtown, meaning that the I-5 tunnel could run much closer to the ground. Nevertheless, traffic patterns would need to change drastically. The tunnel’s four lanes wouldn’t be nearly as numerous as the monstrous 16 lanes I-5 has now. Future traffic levels are a valid concern.

On the other hand, lidding I-5 is a proposal that would largely leave traffic patterns untouched. It’s been gaining traction lately and won a feasibility study via the public benefits package from the Washington State Convention Center. On paper, lidding I-5 sounds like a great idea–and it is. Miles of land between Downtown, First Hill, and Capitol Hill, would be freed and would serve as a much-needed extension of Downtown. The loud, polluting cars and trucks would be hidden away from view and be replaced with natural flora.

But it’s a conservative approach. Only the section of I-5 running below-grade between Thomas and Madison streets is capable of being lidded. The rest, such as portions in Eastlake, run atop elevated viaducts. Also the vast majority of the on-ramps and off-ramps remain the same, dumping cars in all the neighborhoods of central Seattle.

Lidding I-5 would leave everywhere else unchanged. The International District, an area historically neglected by the city, would still be left with a giant, block-wide viaduct running overhead. Eastlake would still be cordoned off from Montlake. And we would have to pay for both the lidding project as well as the rehabilitation of the existing freeway.

While planning the new urban spaces for Seattle, we must not forget the 274,000 vehicle trips on I-5 each weekday. By building the tunnel, we will provide a bypass option of central Seattle, potentially improving long-distance interstate trips while nudging people taking shorter trips to shift modes, whether transit, biking, scooting, walking, or rolling. The loss of several on- and off-ramps will be one of those nudges.

Regarding traffic concerns, having less capacity isn’t necessarily a cause for more traffic. It’s the law of induced demand: once drivers notice the new lanes and increased capacity, they’ll start making more and more, sometimes unnecessary trips, while commuters who previously took transit might even get back into their cars. Traffic levels will soon return to normal, even with the new lanes.

Further applying the principle of induced demand, it may seem that removing I-5 altogether would also be a viable option for urban renewal. But a large chunk of traffic on I-5 are cars travelling through the city, such as from Everett to Kent. I-5 is their primary link to all destinations north and south of Seattle. The SR-99 tunnel links to local roads and SR-509 and doesn’t provide the direct link for long-distance travel that I-5 does. Diverting traffic onto other highways such as I-405 would only exacerbate the existing congestion on those roads.

Moreover, I-5 is essential for truckers to efficiently get where they’re going. “WSDOT estimates an average of 16,000 trucks carry goods through Seattle on I-5 every single day, moving more than 81 million tons of cargo annually in Seattle alone,” Lester Black reported in a recent Stranger feature on the future of I-5. Not all of those trips can end up on SR-99 or other northward routes from the Port of Seattle.

The lowered capacity of the tunnel will discourage excessive travel; people will actively begin to look for alternative ways to get downtown–and we will have those in droves. Sound Transit 3 and the ongoing expansion of light rail service will play an essential role. King County Metro also has an ambitious “Metro Connects” plan to add RapidRide service, and Community Transit has big bus rapid transit plans in Snohomish County. All in all, the tunnel will be there for those who need it and those who don’t will have other options.

Above ground, the removal of the current I-5 will spark an urban renaissance. It opens up acres of land for green development. The Cascadia high-speed rail could run through cut-and-cover tunnels constructed where the sunken freeway used to lie. New apartments can be built between South Lake Union and Capitol Hill. Skyscrapers can stand between Downtown and First Hill. Parks can rejoin the two sides of the International District that have been split apart. Streets that have been severed for 50 years could finally be connected again. Affordable housing can finally have public land to thrive. Where there was noise and pollution there would be life and nature.

But today I-5 is still crumbling. We have the chance to shape our city’s future. Burying I-5 connects people from afar while bridging together those near. Together, we can build a Seattle that we will be proud of in the next 50 years.

Brandon Zuo is a high schooler and enjoys reading about urban planning and transportation. They enjoy exploring the city on the bus and on their bike. They believe that income and racial equality should be at the forefront of urban development. Brandon Zuo formerly wrote under the pseudonym Hyra Zhang.