Pedestrians attempting to crossing Denny Way while walking on Westlake Avenue’s east side will find they are only allocated around ten seconds of walk time to get across the four lanes of traffic. If they decide that they can’t make it across the street in time, they will wait for 70 more seconds to get to cross. During that time, dozens of pedestrians will often queue on the sidewalk waiting to cross, particularly during rush hour, as Denny Way often turns to stop-and-stop traffic.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is working on upgrading traffic signals on Denny Way between Uptown and I-5 at a cost of approximately $9.8 million, with the goal of moving more vehicles through the corridor outside of peak times. The project will install new curb ramps and tactile strips at pedestrian crossings, but the SDOT’s signal team told The Urbanist “we do not expect pedestrian or vehicle wait times to change during peak times due to this change.” The department will be adding Leading Pedestrian Intervals, which provide an extra few seconds head start to pedestrians before the green light “where feasible.”

The new adaptive signals will allow traffic engineers to alter timing remotely at the push of a button or tuning of an algorithm, as opposed to conventional signals that require sending a technician to the signal box to manually alter the programmed intervals. Although boosters say adaptive signals offer flexibility, their initial focus is moving more cars.

SDOT says that while pedestrians walking east-west along Denny Way will not have to press a “beg button” to get the crossing signal, people trying to cross Denny north-south at some intersections will after the signal upgrade. Thus, if a cross-street gets the green light, a pedestrian may not get the walk signal at the same time if they have not hit the button. At most major streets, like Westlake and 5th Avenue, they will not have to hit the button.

Pedestrian advocates asked the City to delay implementation of adaptive signals until it addresses the negative impact to people walking, rolling, biking, and in transit. When the Move All Seattle Sustainably (MASS) coalition–of which The Urbanist is a founding member–formed last year, one of its first asks was no new adaptive signals until the technology “can measure and mitigate delays to people walking.” While SDOT has a “pedestrian surge” detection pilot planned, the City is still moving ahead on Denny Way without that technology ready.

The nearly $10 million to convert Denny’s signals to adaptive ones, like the ones currently in place on Mercer Street just a few blocks north, is a key component of the transportation projects that are being completed as part of the renovation to the Seattle Center Arena. As part of the transportation investments they are required to make to mitigate event impacts, Oak View Group is contributing around $2 million to upgrade the signals. The other sources of funding are city funds, Port of Seattle money, and a grant from the Puget Sound Regional Council.

Just like 2nd Avenue, where a segment of protected bike lane is being removed to provide a wider exit corridor for vehicles after events, Denny Way is being “optimized” to get vehicles from the renovated arena to a major highway as quickly as possible. A short stretch of Harrison Street between Seattle Center and the northern entrance to the SR-99 tunnel will also be equipped with adaptive signals.

The rollout of adaptive signals on Mercer Street happened quietly. Uptown residents (like Carolyn Mawbey) noticed that walk times had gotten shorter and that pedestrians were being denied the walk signal long before the parallel green light had ended. That was because the centralized control of the network was “adapting” to demand for vehicles, and changing signal times accordingly. Because it had to provide a minimum time on the pedestrian count-down clock, the system would provide that and no extra.

After months of making tweaks to the system, advocates have noticed an improvement. An SDOT spokesperson told us, “We’ve been listening to feedback about we received from pedestrians after implementing adaptive signal operation system along Mercer St in South Lake Union, and are planning to learn from this feedback and experience going forward. Our goal is to find a multimodal balance for all users, and to enhance safety for everyone including people on foot and people with disabilities.”

But finding balance is what’s required when the goal is moving as many cars as possible. SDOT told us that they “do not expect a significant change to traffic [volumes] on Denny Way due to this project,” and yet the department has consistently touted how many cars it is moving on Mercer Street thanks to the adaptive system.

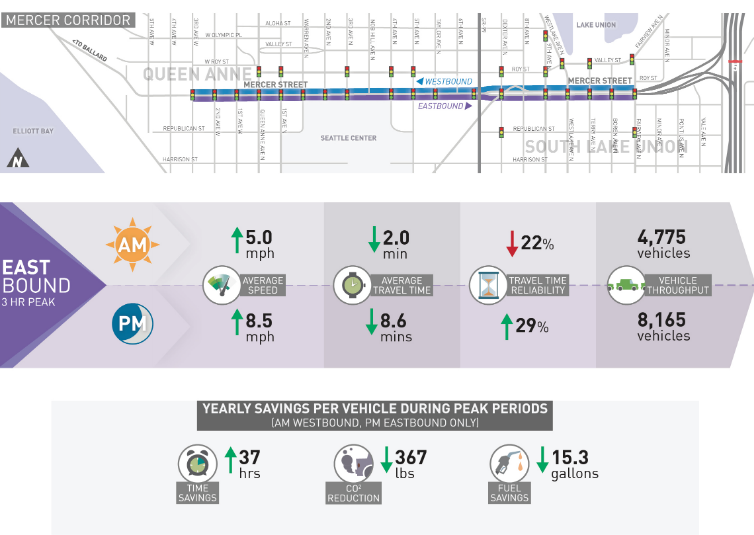

According to the most recent update from Mercer Street this past June, the average time saved for a driver heading toward I-5 during the PM peak was 8.6 minutes. SDOT claimed someone commuting to South Lake Union using Mercer Street was saving 367 pounds of carbon emissions every year due to the adaptive signals! Of course, that isn’t compared to someone not driving at all.

Crossing Mercer Street is a daunting task for a pedestrian, or someone rolling though the intersection. And the adaptive signals have not ensured that crosswalks are clear when the walk signal finally comes up to cross: drivers frequently crowd the crosswalk at intersections like 9th Ave N, often even blocking the marked crossings laid out for people biking. Billing adaptive signals on Denny as an opportunity to better balance different modes belies the current Mercer Street experience that still almost no one is happy with.

If making signals adaptive simply moved the existing number of vehicles through a corridor as fast as possible, that might translate to fuel savings and allow more crossing time to be allocated to pedestrians, or transit vehicles trying to get across that corridor. But that doesn’t account for more people driving on the street once it becomes a faster route to get to I-5–also known as induced demand. During peak times, demand for space for vehicles far outstrips supply on Denny Way. Adaptive signals will throw gasoline on the fire, not water.

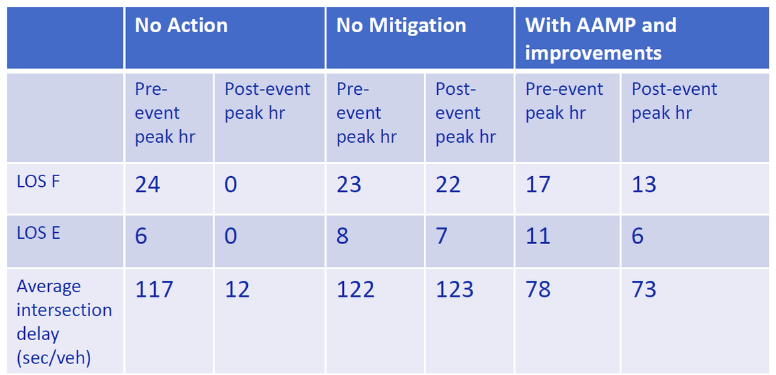

And then there’s the arena traffic management, the primary purpose for the project. We don’t know exactly what the expected impact will be from Denny Way’s adaptive signals alone. According to arena transportation documents, the slate of improvements planned will mean that instead of 23 intersections around the arena performing at grade “F” level-of-service before an event, there will be 17. After events, that will go from 22 to 13. Level of service for pedestrians was not measured. Transit service to the arena will benefit from new bus-only lanes on 1st Ave N and Queen Anne Ave N, but not on Denny Way, where it has been determined there’s no space.

Average delay at an intersection is predicted to go from around two minutes to less than 90 seconds. This gives a rough idea of the impact to current wait times crossing Denny Way before and after events: assuming no additional traffic is not added to the corridor, enticed by lower travel times.

The Denny Way corridor has begun a real transformation as the South Lake Union rezone set the highest height limits close to Denny. New residential and office towers will turn Denny Way into more of a canyon than it is today. With more than 2,000 new parking spaces in the permitting or construction stage for buildings directly on Denny Way, a $10 million upgrade to the street will further entrench the street as a place for cars, diminishing the experience for anyone else spending time there.

In a city where car ownership is dropping and vehicle miles traveled has stayed flat, investing $10 million in upgraded signals to move cars faster is a blunder that will increase vehicle emissions. This project represents a setback in advancing the multimodal goals that the City says it has.

Editor’s note: The post below has been updated to clarify when exactly pedestrians should expect to be required to use a “beg button” to cross Denny Way after the ITS project is completed.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.