The Urbanist is co-hosting a Tenant Rights Bootcamp on Wednesday, December 4th with renter advocacy nonprofit Be:Seattle. The bootcamp is from 6pm to 8pm at Ada’s Technical Books and Cafe in Capitol Hill, and rent control will be a major topic of conversation.

Be:Seattle describes its tenant rights bootcamps as a “neighborhood-by-neighborhood series teaching renters how to assert their rights, to find solutions to various issues, and to organize for better living conditions for tenants.”

In the past few years, Seattle has been working to establish a “tenant bill of rights,” but more policies are need to slow displacement and root our discrimination. The City has scored successes with the passage of tenant protections like a cap on move-in fees, a ban on source of income discrimination (protecting housing voucher holders), and a “first-in-time” mandate that landlords accept the first qualified tenant—recently upheld by the Washington State Supreme Court.

Even as Oregon has passed a statewide rent stabilization policy, rent control remains elusive in Washington state; residential rent control is banned at the state level. Councilmember Kshama Sawant, who often reminds people she’s an economist (albeit of a Marxist rather than neoliberal variety), has been a staunch supporter of rent control and ran on the policy in her recent successful bid for a third term. Sawant hopes to pressure the state into repealing the ban, as Representative Nicole Macri (D-Seattle) proposed in 2018—though the bill never went anywhere.

Sawant’s reelection proves tenants are a political force in Seattle—and one not easily manipulated by a deluge of corporate cash spearheaded by Amazon. We’ll be discussing how to make sure tenants’ issues stay front and center and that our housing movement continues to grow and flourish.

While rent control is held up in many introductory economics classes as a classic example of ineffective price ceilings—a real boogeyman—there are signs cracks are forming in the consensus against rent control. Some are suggesting that rent control could be a similar trajectory as the minimum wage: formerly dismissed by economists before empirical research showed that simplistic models didn’t predict real life effects; instead, the policy brought great benefits and little of the colossally dire side effects predicted.

This isn’t to say rent control has become popular among economists. It hasn’t. But some economists are publishing research and analysis putting rent control in a more positive light. For example, JW Mason, an economist at John Jay College at City University of New York, delivered a speech at a Jersey City city council meeting last month that succinctly made the case for reexamining rent control. Jacobin, of which he’s a contributor, published that testimony. After running through the recent empirical research, Mason makes this summary:

The main conclusions from this literature are, first, that rent regulation is effective in limiting rent increases, although how effective it is depends on the specifics of the law. Vacancy decontrol in particular may significantly weaken rent control. Second, there is no evidence that rent regulations reduce the overall supply of housing. They, may, however, reduce the supply of rental housing if it is easy for landlords to convert apartments to condominiums or other non-rental uses. This suggests that limitations on these kinds of conversions may be worth exploring. Third, in addition to their effect on the overall level of rents, rent regulations also play an important role in promoting neighborhood stability and protecting long-term tenants.

JW Mason, November 13th Jersey City testimony

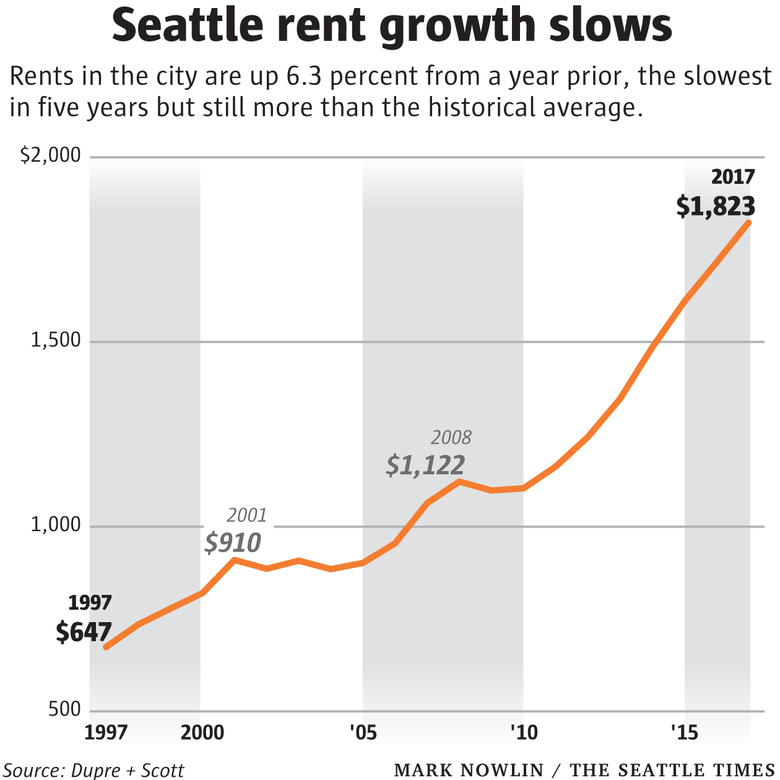

And of course there’s tenants, who are on the frontlines of the landlord relationship, who’ve been sounding the alarm that the status quo stinks. To many of them, rent control sounds like a welcome change to a very one-sided and exploitative relationship. Even if we can imagine a world of housing abundance where rent control may not be necessary, that world isn’t yet near at hand—particularly in booming Seattle with sky-high rents.

Instead, we have cities where affordable housing is very scarce and tenants are incredibly rent-burdened. Mason points out this means landlords can exact monopoly profits and rent control appears a fitting tool to limit that price gouging and promote housing stability.

[I]n many high-cost areas, housing supply is relatively fixed. The reason that existing homes in many large cities cost multiple times more than the costs of construction, is that the ability to add new housing in these areas is very limited, by some mix of regulatory barriers like zoning, and physical or economic barriers. In economists’ terms, the supply of housing in these areas is inelastic — it doesn’t respond very much to changes in price. This fact is widely recognized, but its implications for rent regulation are not. In a setting where the supply of new housing is already limited by other factors — whether land-use policy or the capacity of existing infrastructure or sheer physical limits on construction — rent regulation will have little or no additional effect on housing supply. Instead, it will simply reduce the monopoly profits enjoyed by owners of existing housing.

So if you’re interested in talking tenant rights and rent control, we hope to see you on Wednesday. You can RSVP via the Facebook event page here—though it’s not required to do so. Ada Technical Books and Cafe is at 425 15th Ave E, Seattle.

Be:Seattle has a whole slate of tenant rights bootcamps around town so check out the website for the full schedule and more information.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.