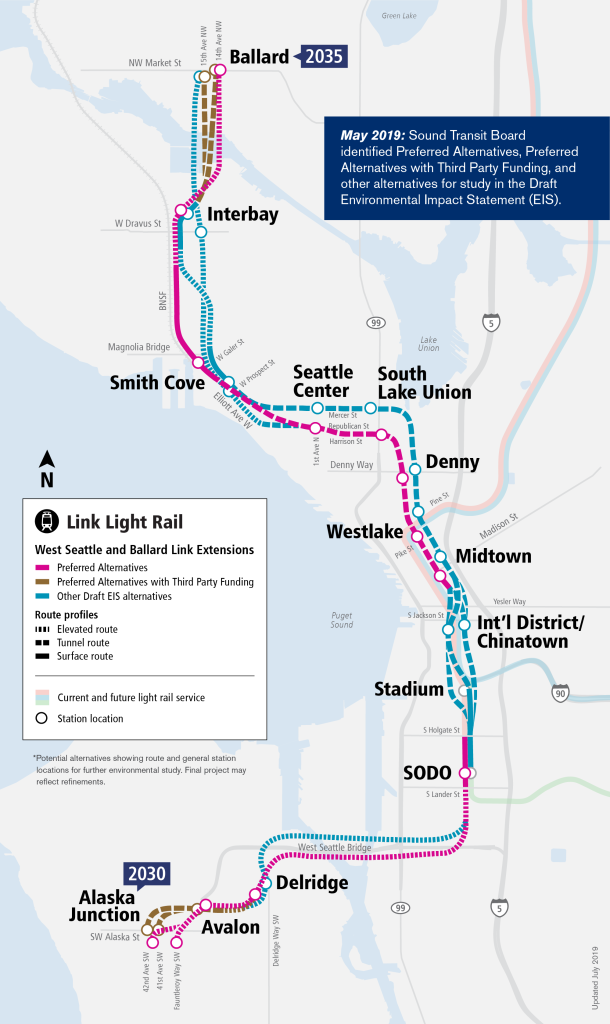

Last week, the Sound Transit Board of Directors made its final cuts for the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) which will hone Sound Transit 3 (ST3) options for Seattle. Gone are the 20th Avenue NW options that place the Ballard Station closer to the neighborhood’s main business district.

Also gone is the most expensive fully-elevated SoDo option and the Pigeon Point tunnel to West Seattle.

The vote is a blow to transit advocates (Seattle Subway and The Urbanist included) that wanted to explore a central Ballard station rather than one at 14th or 15th Avenue NW, well east of the core of the neighborhood. Still, further study could build the case for a 20th Avenue NW station and bring it back into the fold. And we encourage you to keep asking for a Ballard option we’ll be happy with for a century. Sound Transit projects the 20th Avenue NW tunnel would cost an additional $350 million or more, but it may end up being worth it–especially if salmon mitigation becomes a big factor for Salmon Bay bridge options.

Tightening budget spurs suburbs vs. Seattle showdown

Fiscal worries were a major motivation for the board to trim the costlier Seattle options. Federal grant support for transit has been sporadic and unreliable under a transit-hostile Republican administration, but rapidly inflating construction costs in a booming region are also a huge factor: “[Sound] Transit CEO Peter Rogoff is also warning that construction inflation jumped by one-fourth just since 2016, so hard choices lie ahead,” Mike Lindblom reported.

Sound Transit may have to economize; that fight may well end up being a tug of war between Seattle and its suburbs. Seattle representatives make up a minority of the Sound Transit Board. At 750,000 and counting, Seattle has the largest population by far and it’s growing faster than its neighbors, but collectively the Sound Transit taxing district’s population exceeds three million, weighting the board toward the suburbs.

But that’s not necessarily the end of the story. Suburban cities have played hardball with Sound Transit to extract benefits, whether landscaping, station area improvements, or even public restrooms. Perhaps Seattle could follow suit.

Beyond cost anxieties, the dismissal of Ballard’s 20th Ave NW station rests upon the idea that moving the station five or six blocks into the dense core of Ballard would have no impact on ridership. This is what Sound Transit staff have said, basing that bold claim on their preliminary analysis. Further analysis might change that. I’m not sure it passes the sniff test, as I suggested when I wrote about the Initial Assessment report.

Sound Transit has projected ridership would be similar across scenarios, which is a little surprising given that the analysis also finds greater population and job density near a station sited at 20th Ave NW. Arguably, a 15th Ave NW station would provide the best bus connections perhaps compensating for lower density in the area. That said, I’d still wager a 20th Ave NW Station would generate greater ridership–and deeper study may indicate that too. The development opportunities are also considerable.

Pigeon Point dead, but West Seattle tunnels still alive

Also gone is the Pigeon Point Tunnel to West Seattle which added $200 million to negligible benefit. Still, tunnel options that add $700 million to West Seattle Link cost remain for EIS study.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold–who represents West Seattle and is a big proponent of the West Seattle light rail tunnel–proposed raiding money set aside for closing the Center City Connector streetcar budget shortfall to inject a few more dollars into the expensive tunnel project. The revenue Herbold tried to pilfer came from ridehailing fee revenue from the Mayor’s Fare Share Plan. The $56 million would be a drop in the $700 million bucket, but the symbolic and unsuccessful maneuver may have impressed some West Seattleites. She will torpedo high quality transit projects in other districts to fight for our parochial interest. Hooray!

Snark aside, it’s still hard to imagine where $700 million to add this (we’ve argued unnecessary and misguided) tunnel to West Seattle comes from. It’s just a hard case to make when so many other worthy transit projects exist, including extending elevated light rail south to High Point, Westwood Village, and White Center in her own district.

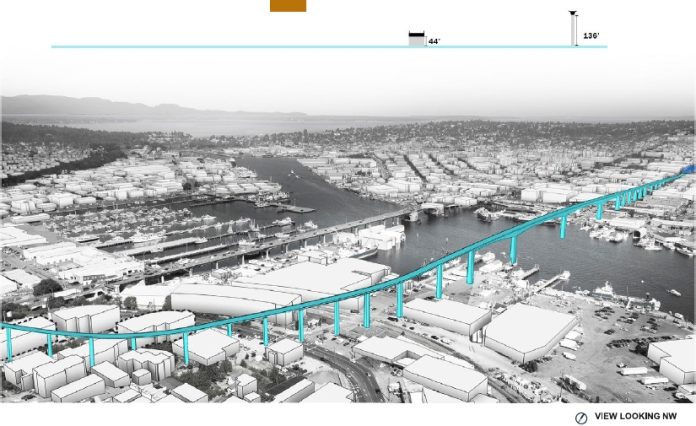

Functionally, a tunnel to Junction isn’t more useful to a transit rider than elevated line that goes to the same place–and elevated lines can serve essentially the same locations. In fact, some riders may ultimately prefer the majestic views that an elevated line over the Duwamish River and up the bluff to Alaska Junction would provide.

In contrast, a tunnel to 20th Avenue NW in Ballard would move the station upwards of a half-mile towards the center of Ballard. We’d lose majectic views, but we’d gain a better walkshed and also solve the problem the Representative Project introduced of a moveable bridge opening for tall boat traffic and disrupting transit reliability. We should be studying a 20th Ave NW option to see if it ultimately would drive ridership and dramatically increase convenience for many riders. Perhaps that logic will win out in time.

You can email feedback to the project team at wsblink@soundtransit.org. You can email the Sound Transit Board at emailtheboard@soundtransit.org. You can also attend a board meeting to comment. More on that here.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.