Years ago I spent a year teaching English in Nice, France, a short train ride from Monaco, a sovereign city-state on the French Riviera famous for its casino, Formula One Grand Prix, and status as a tax haven for international investors. Real estate investment in Monaco provides investors both a safe place to stash their cash and opportunity to evade tax laws in their native countries, making it a popular choice among the world’s elites. In fact, a recent report reveals about 32% of residents of Monte Carlo, the micro-state’s capitol, are millionaires.

Photos of Monte Carlo often focus on glamorous jet-setters partying aboard private yachts, but the reality of Monte Carlo is much quieter than those photos would suggest. Apart from the small historic city center, much of the landscape is dominated by highrise residential towers whose iron-clad window shutters remain closed for the majority of the year. In my experience, Monaco’s streets at night are dark and silent, more bank vault than living city.

With its small size, glamorous reputation, and lenient tax code, it is easy to cast Monaco as an outlier, but real estate has long proven attractive to investors seeking secure investment opportunities, and the global nature of modern life has transformed certain cities into magnets for international investment.

London, for instance, has become one of the most coveted real estate investment markets in the world. Certain segments of the city, such as the infamous Billionaires Row in the North End, have transformed from vibrant neighborhoods to empty vessels for financial investment as stately homes sit unoccupied for years. And despite all of the uncertainty surrounding Brexit, London continues to be popular with investors the world over. In fact, according to JLL Capitol Markets, in 2018 79% of all real estate acquisitions in Central London were made by international investors, a number which its projections expect to remain consistent in 2019 and beyond.

Closer to home, Seattle’s neighbor to the north, Vancouver, British Columbia instituted a foreign buyer’s tax on real estate purchases in 2016 in an effort to curb the city’s stratospheric climb in housing costs, which were partly attributed to a surge of interest in the city’s real estate from international investors. Over the next couple years, the amount of Vancouver’s foreign buyers tax was increased from 15% to 20%, and a tax on empty properties was also implemented, but while the taxes have raised millions of dollar for affordable housing, some evidence suggests most of their impact on cooling Vancouver’s housing market has been superficial. Nevertheless, a growing number of Canadian cities are considering implementing similar measures as rates of foreign investment and speculation continue to surge in real estate markets across Canada.

How are foreign investment and speculation impacting Seattle’s housing market?

Immediately after Vancouver’s foreign buyer’s tax became law, discussion focused on potential impacts on Seattle real estate began. While some early reports highlighted stories of international investors, mostly from China, abandoning high cost Vancouver for relatively budget friendly Seattle, the affect of foreign investment on Seattle’s rising housing prices has garnered less attention in local media than high paid tech workers, a growing population, and zoning codes that favor single-family residences over multifamily development throughout most of the city.

Seattle’s post-Great Recession growth boom has been one of the most transformative in the city’s short history. But even with area median income (AMI) at historically high levels, and documented unemployment rates at record lows, it is difficult to ignore uneven nature of the economic recovery, particular in regards to housing.

“The persistence of poverty amid Seattle’s growing affluence is striking,” said Jennifer Romich, director of the West Coast Poverty Center, in an article with UW News. “While many people benefit from our strong local economy, we should keep in mind that 1 in 9 Seattle residents lives below the poverty line.”

Intractable poverty paired with rising housing costs can also be connected to the increase in the number of people living unhoused on Seattle’s streets, and this visible poverty is unescapable in Downtown Seattle, where unhoused residents live in makeshift tent encampments beneath the city’s growing skyline. The fact that many of those buildings are luxury condominium towers makes for particularly uncomfortable juxtaposition. It also invites questions as to who exactly benefits as these luxury properties increase in value.

In 2017, local activist Cary Moon and writer Charles Mudede examined this question–and more–in their four part series in The Stranger on the influence of speculative investment on Seattle’s housing market. The series, which was published during Moon’s unsuccessful bid for mayor, promoted the concept of a “non-resident real estate speculation tax” modeled after’s Vancouver’s foreign buyers tax. The idea failed to garner broad support amid allegations of xenophobia and questions around how much impact the measure would have.

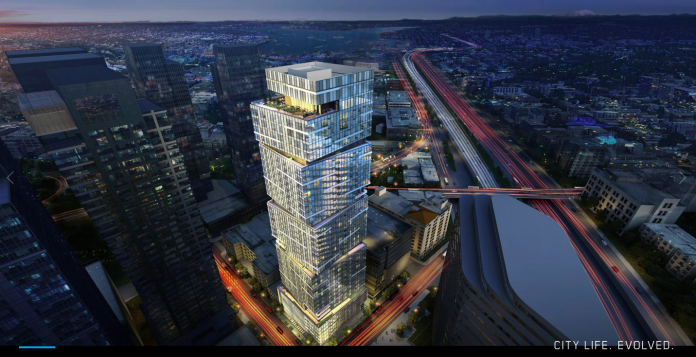

The Spire is a 41-story, 350-plus-unit condominiums building currently under construction South Lake Union. In a news release on its project website, The Spire developers boast of setting a “new standard for luxury” in the Downtown Seattle housing market. The Spire is not planned to include rental units. (Credit: The Spire)

Flash forward to 2019, a new report Who is Buying Seattle? The Perils of the Luxury Real Estate Boom for Seattle published by The Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), a Washington, D.C.-based progressive think-tank, shows that thousands of new luxury residential and rental units continue to be in different stages of development in Seattle, and that many of these properties are owned by limited liability companies (LLCs) or real estate investment trusts that mask the real owners and beneficiaries identities.

Moon and Mudede reported in 2017 that real estate investment trust ownership of multifamily housing owned 8.2% of the total housing inventory, making Seattle the eighth highest-ranked city for real estate investment trust ownership. IPS’s findings suggest that the trend Moon and Mudede identified back in 2017 may have continued to increase; of eight existing luxury condominium buildings examined in IPS’s report, 12% were identified as owned by limited liability companies (LLCs) or REITs (real estate investment trusts).

Additionally, IPS found that the more expensive a unit was, the more likely it was to be owned a trust, trustee, LLC, or other corporate entity.

At the 99 Union condominium development, best known as the site of Seattle’s Four Seasons hotel, 47% of the units are owned by trusts, trustees, LLCs, and corporations. In only 19% of units was the owner registered to vote there.

It is unknown at this point what effect speculative investment in luxury markets is having on Seattle’s housing market; however, the IPS report indicates that it could be worthwhile for these trends to be further studied as more and more luxury highrise developments reshape Seattle’s skyline. “The burden is on the city to show how this building boom will benefit ordinary Seattle residents and not worsen economic inequality in the city,” said Chuck Collins, the lead author on the report and senior scholar at IPS.

IPS recommends the City of Seattle require more transparency around ownership interests in luxury properties through policies such as requiring municipal disclosure. In terms of helping to curb negative effects on housing affordability, IPS encourages state lawmakers to strengthen Washington State’s Real Estate Excise Tax (REET) to include higher tax rates on luxury buildings and more resources for Seattle. State and local lawmakers could also implement a vacancy tax similar to the one levied in Vancouver, B.C.

Condos are not the problem

Watching luxury condos rise above people who are struggling with homelessness in Downtown Seattle can feel particularly egregious; however, it’s important to remember that the vast majority of luxury properties in Seattle are not condos. According to a 2018 article in The Seattle Times, 69% of residential plots of land in Seattle are occupied by single-family residences. By contrast in Boston, a city not known as a concrete jungle, the number drops to just 14%.

By and large the majority of luxury or high priced properties in Seattle are single-family residences. According to the most recent figures, the median price for a single-family residence in Seattle is $760,000, while the median condo price is $450,000, roughly 41% less expensive.

During the public hearings that led to the passage of Mandatory Housing Affordability, anti-density activists used the construction of luxury condos in Downtown Seattle as proof that increasing density leads to higher housing costs. While luxury condos certainly do not help to ease the housing affordability crisis, they represent only a fraction of Seattle’s housing stock and should not be blamed for the current housing crisis.

Additionally, neither IPS or any other research firm has studied what percentage of real estate investment trusts, LLCs, or other corporate entities are investing in single-family residences in Seattle because examining the ownership records of single-family residences would be much more time consuming than examining records for multifamily properties. Considering the fact that single-family residences generally have more stable market value than condos, it is probable that rates of investment by these entities in single-family residences are as high or even higher than in luxury condos.

Implementing taxes like Moon and Mudede’s non-resident real estate speculation tax and a tax on vacant properties would raise money for affordable housing, and both concepts deserve close consideration from local government. But luxury condos are not the primary problem. A zoning system that favors single-family residences is the real problem and needs to be addressed if Seattle is make progress on resolving its housing crisis.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.