Longtime Streetsblog USA editor Angie Schmitt was in Seattle last week to talk about the pedestrian safety crisis. Schmitt stepped down from her Streetsblog position in September to finish a book on the subject due out in August 2020. She and Anna Zivarts, director of Rooted in Rights, led a discussion at Peddler Brewing hosted by local pedestrian advocacy group Feet First.

I caught up with Schmitt just before the talk to hear more about her research. The Cleveland-based author had just been in Portland to do a similar talk at the invitation of Portland State University, who named her an endowed speaker. (Bike Portland has a great summary of her talk as well.) There really hasn’t been many books or academic research done on the pedestrian safety crisis in America even as the crisis gets markedly worse. Pedestrian deaths are up statewide and in nearly every jurisdiction across the country.

Some smaller publications–and I would include The Urbanist and Streetsblog in that–do talk about street safety, but it can feel like yelling into the void as far as what the agenda is on the regional, state, and federal level. Folks like House Transportation Chair Peter DeFazio (D-Oregon) would rather jump on the next fad–whether autonomous vehicles or hyperloops–than wade into street fights and safety campaigns. We are still a suburban nation more interested in expanding highways than investing in infrastructure for people walking, rolling, biking, and riding transit.

What Schmitt had to say really made me excited for her book to drop. You should be able to pre-order her book (which is being published by Island Press) in July. To track her progress and traffic safety takes, you can follow her on Twitter @schmangee.

Ideas like banning sport utility vehicles (SUVs) or pedestrianizing streets don’t seem so far-fetched after you hear the scale of the problem we face and the corruption under-girding it all. At the very least, the case is clear that much more research on pedestrian safety is needed. Cars have claimed much of our cities and our lives. Automobiles have taken so much from us that we haven’t been able to document it all. In fact, society trains us not to see it. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Below, lightly edited for brevity, is what Angie Schmitt had to say in our interview.

Why is there a pedestrian safety crisis?

What I’m going to try to do with the book–and the first draft is pretty close to being done–is speak to this question of why are so many additional pedestrians being killed than just a few years ago. I don’t think there’s one explanation. I just came from Portland where I spoke at the university and showed this graph which shows this real skyrocketing of pedestrian deaths beginning around 2009. People just want to guess: what’s the cause? Obviously, everyone is curious about it.

A lot of people maybe think smartphones or distraction. You can tie the rise of the iPhone to around that time. But I don’t think it’s any one thing. I think there’s a combination of trends that are underway and some of them have been underway for longer than 10 years. When the recession hit, there was a decline in driving that could have hidden that for a while.

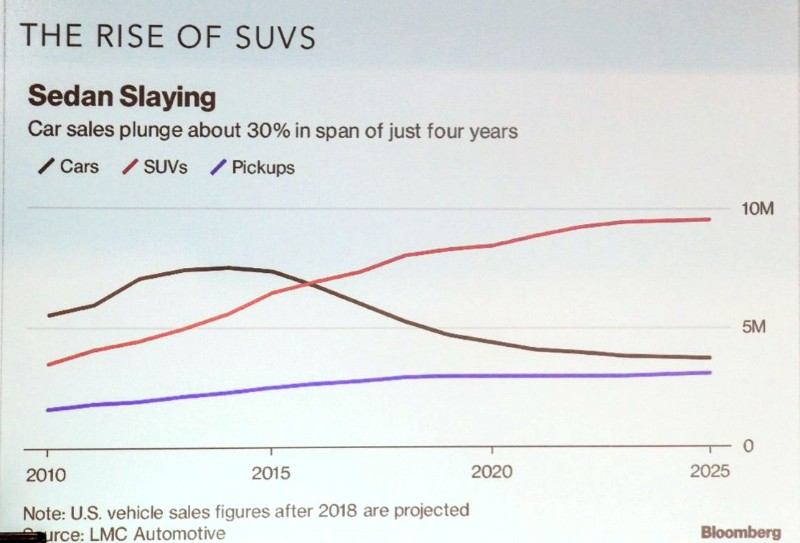

One that I talk about a lot is the rise of SUVs. Cars are getting bigger. Cars are more powerful. They’re more likely to kill pedestrians. Not only are more pedestrians getting struck by cars, but when they do get struck it’s more likely to be fatal. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) did some research on this that’s really important. Some of the other people who have investigated this like the Detroit Free Press have sort of arrived at the same opinion. They basically found that when you look at what’s happening now versus years ago when pedestrian deaths were lower: more pedestrians are getting struck, but collisions are 29% more deadly.

As for the collisions that are happening, it could be one of two things: either they’re at higher speeds or they’re happening with heavier vehicles. There’s really strong data that the federal government tracks–one of the things they track really well is when there’s fatalities what type of vehicle it was. So we can look at the data really clearly and make the connection to SUVs. So there’s really been this real explosion in growth in SUVs since we came out of the recession.

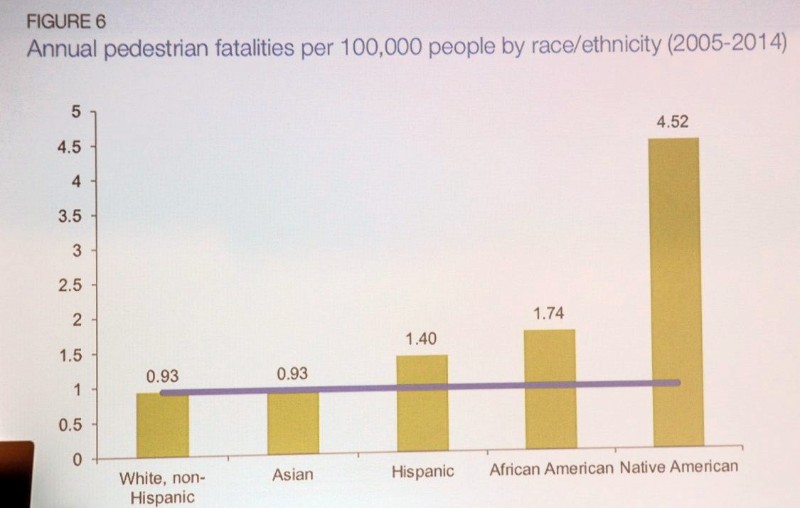

There’s also some demographic trends happening at the same time that put more people at risk, like the suburbanization of poverty. We’re having a lot of growth of poverty and racial diversity in suburban areas that were planned exclusively around the car, and some of the newer residents are more dependent on walking and public transit than previous residents. So, there’s more people in more dangerous areas doing more walking. That creates problems, and then when they’re getting hit, they’re getting hit with heavier, more dangerous vehicles.

Another thing is older people make up a disproportionate share of pedestrian fatalities, and we just have a lot of growth in that demographic group right now, and growth in the Sun Belt, which is the most dangerous area [of the country]. So some of these demographic trends like growth in the Sun Belt and the aging of the population, those sort of just happening on their own would predict a rise [in pedestrian deaths]. Cars getting more dangerous is another thing. Some of these intraregional traffic trends, like when there’s gentrification and people who are doing more walking and now in more dangerous areas, I also think is a contributing factor.

Should we ban SUVs?

I was one of the first people to talk about this. Even before IIHS and Detroit Free Press started reporting about this about two years ago. I started looking at this about a year prior. I was saying “hey guys, SUV’s are a problem” when that was considered a pretty wild idea. And there was a lot of pushback, and I get it because SUVs are really ubiquitous. And people would say, “you’ll never get to ban SUVs.” There’s a lot of steps between what we’re doing right now–which is having regulations that don’t even warn people about the risks of SUVs and instead promote their sale and use–and completely banning them. I think there’s a lot of intermediary steps.

One thing that I think would be low-hanging fruit is we should be regulating bull bars, or maybe ban bull bars. One intermediary step would be to warn people who are purchasing them that: A) this is a danger to people around you, and B) this actually makes you driving around in your car more dangerous because it eliminates the crumple zone. So, it’s actually a risk to you, and we don’t actually warn consumers about this stuff. A) We could ban bull bars, or B) we could at least could require some sort of warning so people who are taking this added risk are at least informed of it.

In 2016, the Obama administration citing this research that showed SUV’s are a lot more dangerous to pedestrians, proposed rating cars based on pedestrian impact. Right now, no one in the U.S. is testing cars on pedestrian dummies. So we know SUVs are more dangerous, but within the whole category of SUVs, now there’s not even a very clear distinction between sedans and SUVs. It’s more like a spectrum.

One question that has come up that I don’t really have a good answer to is: how bad are crossovers? Some experts I’ve spoken to don’t think some crossovers are a problem. Others think probably they are a little in between in terms of risk. Bottomline is that we don’t have a lot of data because no one is crashing cars against pedestrian dummies in a lab in the U.S. like they are in Europe.

So in 2015, at the end of the Obama administration, the DOT [(United States Department of Transportation)] proposed that the five-star safety rating they do was for the first time going to consider pedestrian survivability. Now that wasn’t in a regulation. Currently, there are no car regulations in place to benefit pedestrians at all. That would have been an intermediary step because automakers really want to get those five-star ratings–some of them–and it helps sell cars. But then Trump came into office, he said we’re going to get rid of two regulations for every one regulation we start. They’re very anti-regulation. And that whole thing did not progress. There’s been no progress on that. I know this guy who is an engineer at Honda, and he said Honda was ready to go. They were working on designs to change the front end of their vehicles to perform well in collisions with pedestrians. And they just haven’t heard anything, so these automakers aren’t moving ahead because the DOT under Trump doesn’t value safety, and especially not pedestrian safety.

Why don’t automakers lead on pedestrian safety?

SUVs cost about the same amount of money to make as cars–these crossovers and everything–but they’re able to sell for $10,000 to $15,000 more. So, it’s enormously profitable for them. So these automakers have done a ton to encourage this trend, because they make a lot of money off of it.

So if you read this book that I talk about all the time called “High and Mighty” by Keith Bradsher–he used to be a New York Times reporter–the psychology of it is really fucked up. People have this violent aggressive impulse that these auto companies are accommodating and encouraging with these vehicle designs. They interviewed marketing executives from the Big Three automakers. At first, it was mainly the American automakers that were doing SUVs; they were just converting pickup trucks, and putting a different top on pickup trucks and fancier seats and selling it for 20,000 extra dollars.

One thing they say in the book was that one of the pioneers of SUVs–he was like a marketing guru–he said Americans are terrified of crime, and he said it’s not really very rational. It’s not based on statistics or anything like that. It’s sort of just based on because we consume a lot of violent media is what he said. So we watch police shows and stuff like that where there’s all this gruesome stuff, and it really impacts the way we see the world. So, they want a car where they can run someone over if someone threatens them on the way to the grocery store. And they were profiting off of that impulse and encouraging it.

Is cheap gas responsible for this trend?

What [Brahsher] says–the book is a little dated at this point [(it was written in 2002)]–he said at least at the time the people who were buying SUVs are pretty wealthy. Right now, new car buyers tend to skew pretty wealthy just in general. What he said is that among wealthier people, gas prices don’t matter that much. They don’t care that much. It’s not a very big part of their income. But for lower-income people it really is.

But around the time the recession happened, there was a big spike in gas prices and SUVs went out of style. But now that they’re low, I think it does encourage it.

What is the role of Uber and Lyft in this problem?

Nationally, I don’t know if it has had a huge impact, but I don’t think it’s helped because they’ve added a lot of vehicle miles traveled–and especially in pedestrian death areas. And they don’t really do any training with their drivers and I don’t think the financial incentives the companies offer really promote safety either. Probably the opposite.

I think it will vary a lot, because they’re primarily in nine metro areas, nine big cities. And the cities they’re in tend to be the safer ones for pedestrians. But still, in a city like San Francisco where one out of five trips is in an Uber or a Lyft, for sure it’s had an impact. Seattle’s probably a little like that as well. City officials who are trying to meet these Vision Zero goals are having to deal with this new product that sort of supercharges driving–that increases driving in areas that are in some ways aren’t that well suited for it. I don’t think it’s a big factor nationally–although I don’t think it’s helpful–but, in some of the big cities where they a large percentage of trips, probably it is more.

One study estimated Uber and Lyft are involved in a surprisingly high number of traffic fatalities, but we don’t really know, because the companies don’t turn their data over, which is bullshit. Even safety data. It’s ridiculous that they’re allowed to operate in all these cities without turning over basic safety data. They would never allow the scooter companies to do that, but in that case they’re collecting the data themselves and analyzing it really carefully. Not as much for Uber and Lyft.

[Uber and Lyft] haven’t made money for a decade. So how long will they keep doing that? Who knows. It’s such a weird thing. Will they start making money? No, probably not. [They say they make money] if they exclude their overhead and all the money they put into marketing and that type of thing. The last I heard, they had laid off a third of their marketing staff and they still had like 800 people doing marketing at Uber.

Are any presidential contenders elevating this issue?

No. I haven’t heard any of the presidential contenders say anything that would bring up traffic safety at all, even though I’ve read their climate change plans. So, no it hasn’t made it into any discussions I’ve seen.

Ayanna Pressley out of Boston–she’s one member of The Squad–she’s pretty engaged in urbanist issues, and she just helped form and she’s going to be one of the chairs of the mass transit caucus, and she’s also in the bike caucus. That’s sort of promising. But among the presidential candidates, who knows. None of them have said anything about it that I’ve heard. One exception is Bill de Blasio, who is no longer a presidential candidate. He did bring up this idea, sort of off hand, of a national Vision Zero. People who work on this stuff sort of jeered at him, and I wrote an article defending him–I’m not like a Bill de Blasio fan or anything–but yes, this should be part of the conversation.

I read this traffic safety book by Neil Erickson. He’s part of the provincial government of British Columbia doing traffic safety stuff. He wrote this really good, really long book about how to end traffic deaths in Canada. He said in countries that have much better safety records that us–like France–the president will make traffic safety one of their top priorities. He uses an example where the former president of France made traffic safety and reducing traffic deaths his number three priority. He said that’s the level of attention that’s needed to do a lot better than we’re doing.

As of now, it’s still not discussed. They’ll talk about gun deaths, but not traffic deaths.

I believe it’s a similar [number of deaths between the two]. And it’s equally amenable to policy. A lot of people think we could do a lot to reduce gun violence with better policies. Traffic is the exact same way. Exactly. We know there are things we can do and we can predict with a lot of accuracy how many lives will be saved, and we just choose not to do them. People don’t believe the science of traffic safety. They’re skeptical. They turn into anti-vaxxers about traffic safety research, and they just dismiss it, sadly.

Comparing Cleveland and Seattle

They definitely very different. Seattle is way ahead of Cleveland on transportation. It’s sort of dumb luck on Cleveland’s part, but here’s there so much homelessness compared to where I’m from, and it was the same in Portland. It seems like such a big problem, and it’s not my area of expertise so I don’t know what to recommend. We don’t see that so much there. That’s one way we compare favorably. We don’t have the crazy housing crisis, but it’s a totally different economy. We have the opposite problem where our economy is just garbage. That comes with its own set of housing problems like vacancy and stuff like that.

One thing that was cool about Portland–and I don’t know that Seattle is any different–is how many people who were working on these issues. We only have two or three guys over our whole traffic department doing everything–signals, resurfacing, everything. Portland has six people working on Vision Zero. The sophistication of the staff and scale of resources is just really different.

How do cities that have made progress keep from getting complacent?

People in Portland–coming from Cleveland it seems really great like Portland wow, but I didn’t get to see how it progressed over time–everyone was still frustrated. And I think that’s it a good sign everyone being frustrated. In cities that are doing better, a lot of people feel that: they’re not satisfied; they’re really engaged. They feel like sort of confident that they can influence the direction of the city. That’s a good sign.

There’s not one formula. On traffic safety issues, there just needs to be more attention to it, and I think a lot of the little actions people are taking all add up. There’s not a lot that won’t be solved by way more attention to the issue. Issues are always competing for attention, but traffic safety in a lot of areas doesn’t get the attention it deserves considering how many people it kills or injures every year. Even in a city like this where there is a lot of attention to it, people’s contributions to keeping it on the forefront of people’s minds and fighting those difficult political battles is really helpful.

The best thing anyone can do is get more people engaged. There’s so much work to do. In Cleveland, when I started doing this stuff and talking about it ten years ago, there was just a few of us working on it, and there’s so much work to do. And now I don’t really work on it that much. I complain about something and there’s these smarter, younger people that are speaking on projects and pushing things forward. That’s much easier than trying to do all the work yourself. So winning people over and getting them involved is really important.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.