Mountlake Terrace adopted notable changes to its primary urban node, expanding its boundaries and increasing development capacity near its future Link station. The city refers to the area as “Town Center”–much of which is fairly low-slung post-war development, though the area is beginning to see some re-invigoration with modern development and investment.

The city is one of the latest to revise its zoning in anticipation of light rail with Lynnwood and Shoreline recently overhauling zoning and development regulations near their future stations. Edmonds and Everett also doubled down on transit-oriented zoning to make better use of existing high capacity transit investments in their communities, and Snohomish County is in the midst of station area planning in advance of light rail that could result in zoning changes near Ash Way and Mariner Park and Ride–both future Link stations.

Building upon the previous subarea plan for the Town Center district, Mountlake Terrace hired Makers Architecture and Urban Design to assist city planning staff in formulating a subarea plan and proposal to regulate modern, mixed-use development that new regulations will allow. Boundaries of the Town Center were expanded to include all blocks between 58th Ave W and I-5 from 230th St SW to 236th St SW–a six by three block area.

An earlier proposal for Town Center had sought to expand zoning changes a little more at the edges east of 55th Ave W, but that was pulled out in response to community concerns and reformed in other ways for the adopted proposal. The adopted Town Center Boundary on the new Comprehensive Plan future land use map includes some of these transitional buffer-type lots, but from a regulatory standpoint they are treated different from the core Town Center-zoned lots. Nevertheless, the adopted plan does stick with the vision for buildings up to 12 stories near the future light rail station opening in 2024.

Much of the existing land use in the Town Center area is residential. The subarea plan highlighted this, indicating that 70% of the acreage is currently in residential use–and 83% of residential land is single-family detached residential use. The zoning changes will help increase development across the new TC-1, TC-2, and TC-3 zones over the next 20 years. The city estimates that Town Center, on the high end, can accommodate up to 8,410 new homes and 1,190,660 square feet of new commercial space. Most of the four-square-mile city will remain single-family zoning even with the more intense changes at the Town Center.

Zoning changes

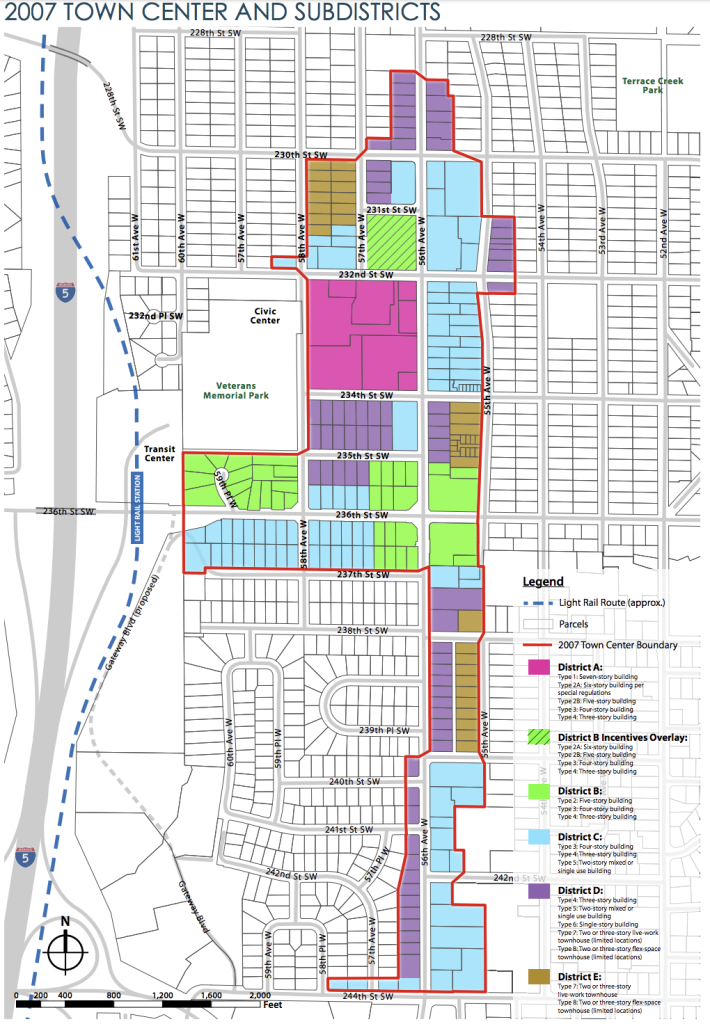

To understand the zoning changes, it is important to have a context for the existing zoning in place. Town Center has five general zoning district types, each of which has several sub-districts to regulate the kind of uses and building height allowed. The most intensive building type allowed is on the large suburban commercial block near Civic Center and Veterans Memorial Park with seven-story commercial and residential uses permitted. This approach is simplified somewhat with the new regulations.

The new Town Center will have four general zoning types (ordered least to most intensive):

- Reserve District (TC-R), which will permit buildings ranging from two to four stories;

- District 3 (TC-3), which will permit buildings ranging from four to six stories;

- District 2 (TC-2), which will permit buildings ranging from four to eight stories; and

- District 1 (TC-1), which will permit buildings ranging from six to 12 stories.

Functionally, the different zoning districts of Town Center will encourage the following types of development:

- The TC-R zone is primarily focused on small-scale retail, multifamily, and professional office uses.

- The TC-3 zone is focused on providing housing. Multifamily residential uses are emphasized throughout the zone. However, pedestrian-oriented retail uses are allowed as part of mixed-use development along 56th Ave W.

- The TC-2 zone is focused on providing community commercial and cultural activities. The types of uses allowed include restaurants and active non-residential uses on ground floor frontages along 57th Ave W from 231st St SW to 235th St SW as well as on eastern side of 58th Ave W from 232nd St SW to 231st St SW. These uses are also allowed on key corners and along 234th St SW and 236th St SW within the zone. Multifamily residential uses are otherwise allowed on ground floor frontages on other streets or as part of vertical mixed-used development on the aforementioned streets. Professional office and lodging uses may also be permitted in the zone as a secondary use.

- The TC-1 zone is focused on realizing transit-oriented development since it is closest to the future light rail station. The types of uses allowed include a broad set of commercial uses (i.e., professional offices, restaurants and retail, lodging, and services) as well as multifamily residential uses. Generally, multifamily residential uses are encouraged as part of mixed-use development, but are allowed in a limited capacity in standalone structures.

Mountlake Terrace does have a clear vision for how it wants streets to function in the Town Center. The plan and development regulations call for upgrades to existing streets as well as entirely new streets. Several new streets will be created on:

- 231st St SW from 60th Ave W to 57th Ave W;

- 233rd St SW from 58th Ave W to 56th Ave W; and

- 57th Ave W from 231st St SW to 236th SW.

How streets will be built out depends upon their classification, of which there are four types.

The Pedestrian Core Streets are wider streets with significant space for pedestrians and on-street parking to facilitate patronage of street-level businesses. Town Center Streets are functionally similar, though they have smaller sidewalk areas.

Interestingly, the development regulations call for Access Corridor streets, which require public access easements ranging from 30 feet to 40 feet. The purpose is to break up large blocks while discouraging major through-traffic. Developers will be able to provide these as either pedestrian-only accessways or woonerf-like accessways with heavy vegetation.

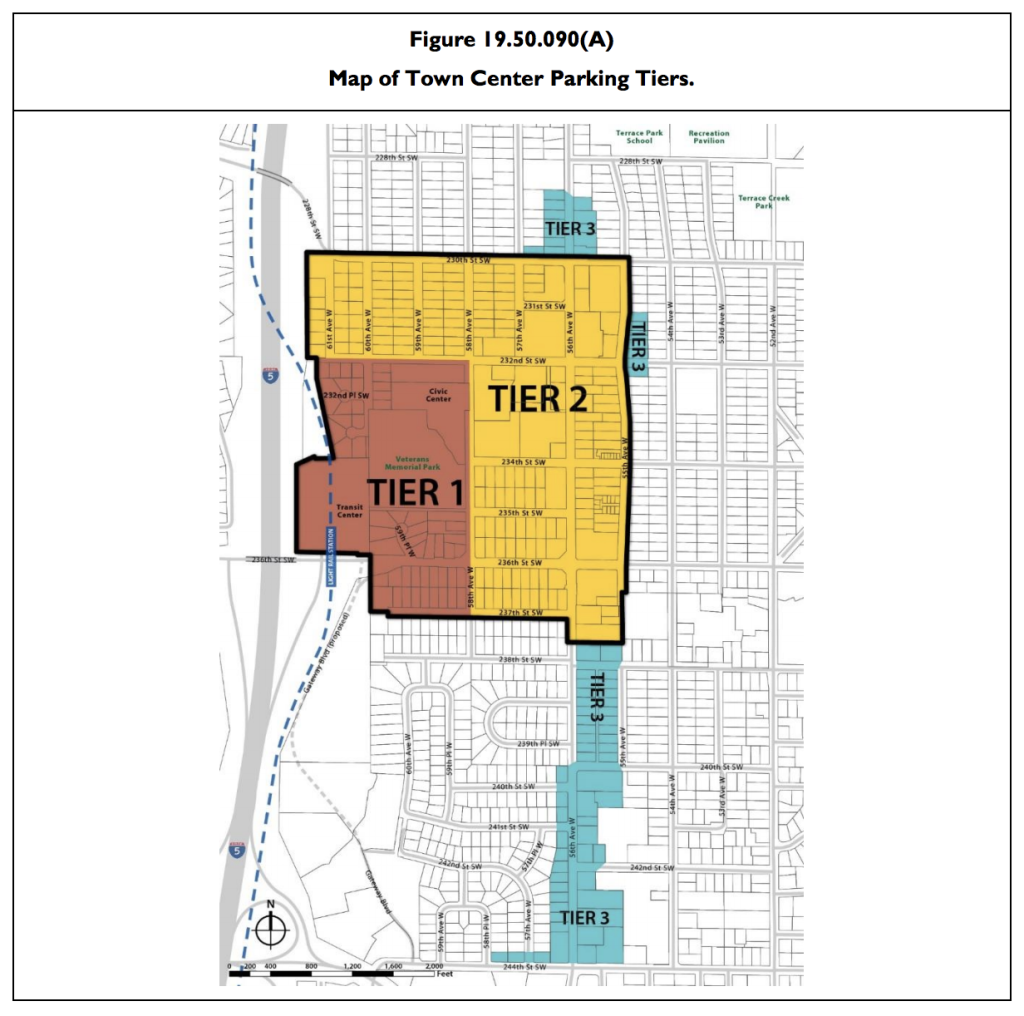

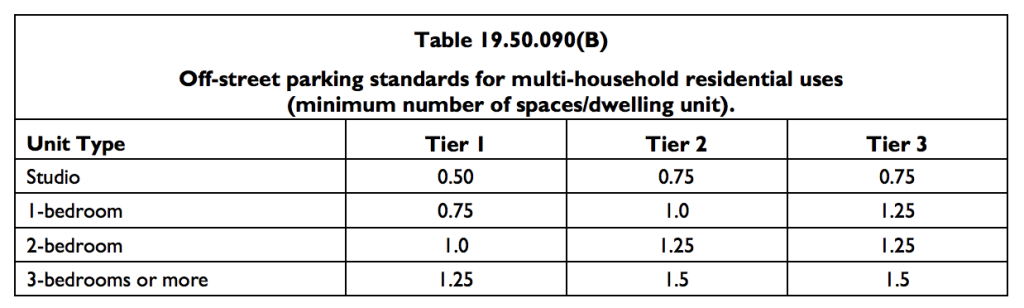

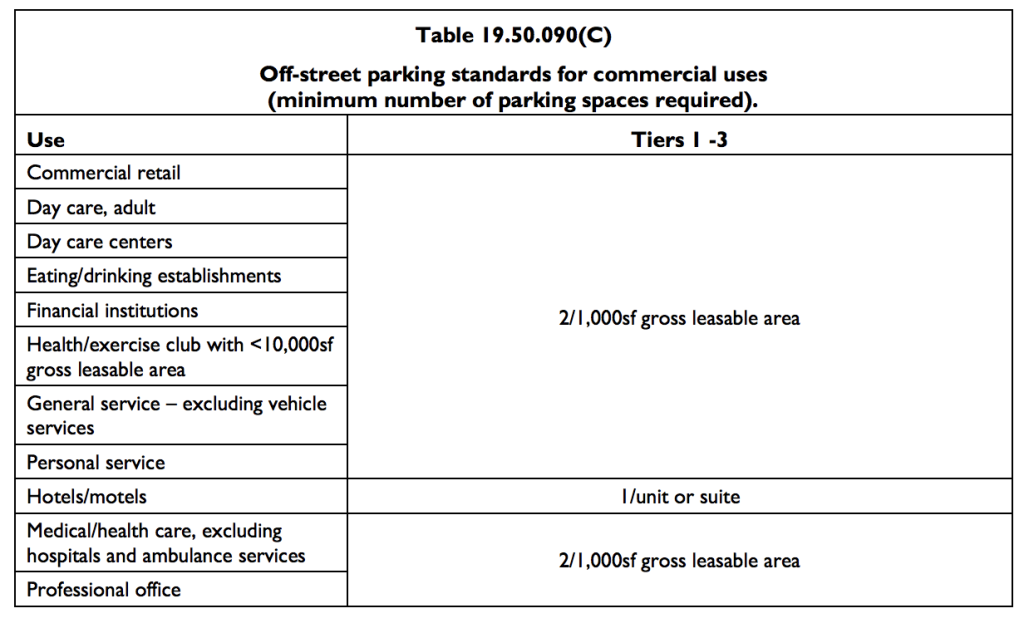

Off-street parking requirements in Town Center are determined by the Tier zone and type of use. There are three Tiers with Tier 1 having the lowest off-street parking requirements. The parking requirements are as follows:

No bicycle parking is required within Town Center, despite its proximity to transit and future light rail.

To better guide the form and feel of development, the Town Center zoning comes with new urban design regulations. Three types of block frontages are outlined in the regulations, which specify Landscaped, Secondary, and Storefront blocks.

The three block frontage types differ in what is allowed and encouraged. Storefront block frontages restrict ground-level parking on street frontages, prohibits ground floor residential uses, establishes pedestrian-oriented amenities, and regulates space requirements for ground floor commercial spaces. On the other end of the spectrum, Landscaped block frontages encourage more breathing room between buildings and the sidewalk with landscaping and lower transparency requirements.

The level of transparency required by the different block types varies substantially. Storefront block frontages are expected to have almost the entire street-level facades be transparent with 70% transparency. Those requirements quickly drop off for the other block frontage types with 40% to 20% transparency on Landscaped block frontages, depending on whether the ground floor is non-residential or residential. Secondary block frontages vary between the two.

To emulate other pedestrian-oriented districts in the area, the Storefront block frontages are chalk full of regulations to promote a modern mixed-used district:

On certain street corners, the Town Center regulations recognize that there are high-visibility areas. The development standards require that new development contribute to these corners in a meaningful way to engage the public. Strategies to be employed include: corner plazas, decorative building materials to accentuate the corner, articulation of the building facade, building sculptures, or a cropped building corner for a prominent entryway.

To manage the scale of buildings and compatibility to surrounding properties, there are several bulk regulations included in the Town Center zones:

- Building elevations longer than 140 feet generally require deep vertical modulation on facades. Roofline articulations are also encouraged.

- Though side and rear setbacks are nominal, they can be extensive when abutting residentially-zoned property lines. An equal setback is required to the one in the abutting zone and buildings must stepback at a 45 degree angle at heights above the maximum height limit in the abutting zone.

- Balconies must also be setback at least 15 feet from any residentially-zoned property.

- Multifamily residential buildings will be required to provide light and air setbacks from side and rear property lines generally ranging from 15 feet to 20 feet, depending upon circumstances.

- For buildings over six stories, special stepback requirements apply with a 15-foot stepback for portions above six stories and a 20-foot stepback for portions above eight stories.

- Towers will need to be separated by a distance of at least 40 feet from one another. These type of structures are considered to be buildings or portions of buildings over seven stories.

Other development standards will regulate things like tower design, building articulation, open space or common space amenities, building materials, blank walls, fire walls, mechanical equipment, and utilities.

Whether or not Mountlake Terrace gets 12-story buildings remains to be seen. But the changes to the city’s zoning and development regulations should result in a much more urban and transit-oriented core than the one today.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.