Yesterday Mayor Jenny Durkan revealed her plan to increase Seattle’s ridehailing fee by 51 cents per ride and direct the first five years of proceeds toward two immediate needs. One is plugging a hole in the Center City Connector streetcar project budget; the Mayor says $56 million will do the trick. The other need is affordable housing–the Mayor wants to spend $52 million to build 500 homes targeted at people with hourly earnings in the $15 to $25 range–roughly what a ridehailing driver makes before expenses.

The Mayor would also dedicate $17.75 million to a Driver Resolution Center run by a yet-to-be-disclosed organization. The proposal calls for stronger protections for ridehailing drivers, partially following in the footsteps of California, which just passed sweeping protections. The Mayor aims to include a driver pay study and said she intends to have a policy in place by next summer that guarantees drivers receive the minimum wage of $16 per hour that large employers face, even when accounting for expenses. The study would determine who would implement such a policy.

California did go further, prohibiting ridehailing companies from classifying drivers as independent contractors, upending their already-strained business model and requiring ridehailing companies pay minimum wage and provide healthcare and benefits to full-time drivers. However, Uber and Lyft are planning a $60 million campaign to repeal California’s law via ballot initiative. Uber and Lyft also oppose Seattle’s fee hike and rider protections package, but ridehailing drivers seem to be welcoming it.

“We view this as part of a broad-based package that will address the problem of unfair deactivation, establish driver pay standards with driver input, and at the same time make important community investments in affordable housing and transit,” said Lyft driver Peter Kuel in a statement provided by Teamsters Local 117, which is organizing some ridehailing drivers in Seattle.

Currently the ridehailing fee is 24 cents per ride, which means the total fee would come to 75 cents under the Mayor’s proposal. This is considerably less than New York City’s $2.75-per-ride fee, but on par with Chicago, which charges 72 cents, and similar to Washington, D.C. on lower-cost trips and considerably less on expensive longer trips–D.C. instituted a 6% fee last year. A percentage fee has the advantage of a progressive scale (and not getting diluted by inflation). A $50 run to the airport would net D.C. $3, for example. That long trip would still net 75 cents in Seattle.

Many other American cities have very low ridehailing fees or have failed to implement them altogether. Massachusetts has a 20-cent fee, while neither Los Angeles and San Francisco have fees–despite considerable congestion issues–but are working on it. San Francisco is considering putting a 3.25% fee on the ballot (it’d need to garner two-thirds of the vote). Los Angeles, which has been bleeding transit riders to ridehailing, is still at the study phase, but is kicking around 20 cents.

After the first five years, the portion of the tax dedicated to the streetcar would switch to funding transit, bicycling, and pedestrian infrastructure projects. While the Mayor’s ridehailing fee is many months in the making–apparently recently it went through mediation to finetune the details–the finished product should give many groups–including ridehailing drivers, streetcar supporters, bus riders, cyclists, and pedestrian advocates–something to like.

“This proposal is about ensuring Seattle grows into the city we want to be,” Mayor Durkan said in a press release. “Being a city of the future isn’t just about the incredible gains of the new economy. It’s about being a city where all our workers are treated fairly, our communities can afford to live where they work, and everyone, regardless of income or ability level, has access to high-quality transit.”

The Mayor also promoted her “Fare Share Plan” at a press conference at Yesler Community Center.

Happy End for Streetcar Saga?

Loyal readers of The Urbanist likely recall the Center City Connector streetcar saga with its many twists and turns–long story short, the project is back on, but its targeted opening is delayed until 2026. While at one point the Mayor seemed to be doubting the premises of the project even down to the gauge of the track, she made an about-face and backed the project in January and is now proposing a funding solution in September. Much can happen in seven years, but a dedicated funding source would reinvigorate a project only recently nudged out of limbo–and add some certainty that it will actually happen.

Vocal streetcar critic Councilmember Lisa Herbold, called the Mayor’s funding proposal “fiscally irresponsible,” but it’s not clear if she can rally the votes against it or if she’ll oppose the fee in general. Most other councilmembers have yet to comment, but Councilmember Abel Pacheco did issue a supportive statement and Council President Bruce Harrell issued a positive quote in the Mayor’s press release.

“All [ridehailing] drivers should be receiving fair compensation for their work,” Councilmember Harrell said. “Council will work closely to examine the Mayor’s proposal in a transparent manner and will provide an opportunity for the public to weigh in over the next few months.”

Ridehailing Worsens Congestion

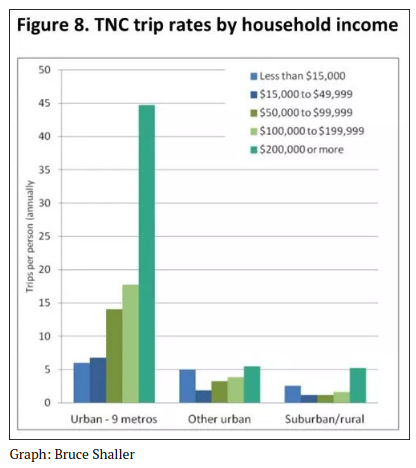

Those hoping that the City would wield ridehailing fees to lower automobile trips and decrease traffic and emissions may be disappointed. Mayor Durkan said she doesn’t expect higher fares to lower ridehailing ridership, which is already incredibly high. In 2018, Uber and Lyft gave about 24 million rides in Seattle, half of which either started or ended downtown, and they expect to top 28 million rides in 2019 and see continued growth in coming years, Mayor Durkan said. Twenty-four million annual rides averages out to about 66,000 rides per day–and recent figures by transportation consultant Bruce Schaller suggests Seattle ridehailing trips peak at 80,000 weekdays.

Academic studies have linked the proliferation of ridehailing to worsening congestion in major cities. For example, ridehailing accounts for 20% of vehicle miles traveled in San Francisco via about 170,000 rides per weekday, and the City blames ridehailing for half of the jump in congestion since 2010. One report claimed 29% of traffic in Manhattan is for-hire drivers.

In many cities including Seattle, Uber and Lyft have come out in favor of decongestion pricing so long as it applies broadly, as they hope to forestall fees targeting just them. Uber even commissioned its own study suggesting decongestion pricing was feasible and could be done equitably, but slyly recommending a daily cap on congestion charges that would benefit the ridehailing industry since their drivers would hit the cap and then pay nothing. Mayor Durkan has also expressed interest in decongestion pricing, but her administration doesn’t appear to be moving quickly enough to implement it by the end of her first term–as she had set as her goal.

Failing Ridehailing Business Model

Efforts by cities to tame ridehailing’s parasitic growth could end up closing any avenue to profitability these companies hoped to have. Uber posted a $5.2 billion loss last fiscal quarter and its slowest growth rate yet. A quarter of Uber’s gross bookings worldwide are in its five biggest metropolitan markets: Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, London, and São Paulo. Seattle is in the second tier, but likely not too far behind. Uber and Lyft’s top nine US markets–Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington, D.C.–account for 70% of ridehailing trips in the US. These cities ratcheting up fees and driver protections would seriously challenge Uber’s model.

For their part, Uber and Lyft claim their drivers already have it pretty good and that the fee would hurt driver earnings and makes rides less affordable. “Drivers will also lose, as their earnings decrease with fewer overall rides,” said Lyft spokesperson Lauren Alexander in a statement. The two leading ridehailing companies claim they pay drivers about $20 per hour before expenses–but expenses are really the kicker when you’re burning your own gas, depreciating your own vehicle, covering your own insurance, and for some reason handing out Jollyranchers and bottled water to ferry around the smartphone-toting masses. It’s also not clear how the companies account for the time waiting or circling in-between rides in their compensation estimates.

Uber is threatening to flex its political muscle to block the proposal. Heidi Groover reported that Uber spokesperson Nathan Hambley said the company would be “reaching out to more than 575,000 active drivers and riders [in King County] encouraging them to reach out to the mayor’s office and voice their concerns.”

Maybe one day we’ll look back on this time in American transportation and just think of it as some weird fever dream. But, for now, onward with the temporary salve of a 75-cent fee on ridehailing trips.

Author’s note: This piece has been updated to include the press conference video, the graph of ridehailing rates by income, and the statistic about top nine American ridehailing markets.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.