Last month, days after the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) finished installing a paint-and-post protected bike lane on 8th Avenue between the Convention Center and Denny Triangle, Mayor Jenny Durkan appeared at a podium next to the bikeway flanked by City staff and advocates. Her appearance there, introduced by SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe, marked the first time the Mayor has appeared at an event focused on bike infrastructure in her first 21 months on the job.

Celebrating the opening of a bike lane is notable, considering that grand opening ceremonies for the bike lanes previously completed under Mayor Durkan’s watch were skipped: the final costs for both the 7th Avenue bike lane and the extension of 2nd Avenue bike lane were published at around the same time, drawing criticism for being much higher than anticipated. Many saw last week’s event as an indication that the Durkan Administration might be trying to get bicycle safety advocates to warm to them. But it would be tempting to read too much into a perfunctory event to capitalize on the completion of Bicycle Master Plan mileage funded through the Washington State Convention Center addition, which contributed $6 million toward the interim protected bike lane that’s there today and its permanent form to be completed in 2023.

For me, the most important thing that happened at the event came after the prepared remarks, when the Mayor was asked (by Heidi Groover of The Seattle Times, in the first question of an impromptu press conference) if the Durkan Administration is treating the street safety crisis in Seattle with the urgency that’s necessary. The Mayor’s response:

Absolutely. As I said, Sam Zimbabwe and I have been talking repeatedly about this and we’ve got to make sure we go in a different direction. We’ve had far too many conflicts and collisions and crashes between pedestrians and bikes and vehicles and streetcars and light rail and we want to double down on that to make sure sure that we go in the other direction. In a city of our growing size, we’ve got to do more to protect people, not less.

In a follow up, when asked what more the administration is doing than previous ones have, she did not name any actions that have been taken:

We’re going to be looking at a range of things including how we use as much of the money coming out of the Mega Block sale to actually focus on Vision Zero. We know from data where those areas are that there’s repeated incidents and we want to focus on those. We also know that we have underspent in the South part of Seattle and we’ve got to get more projects for safety in South Seattle.

There’s a lot to unpack in these comments, with a key point being a Mayor who does not even appear to acknowledge traffic violence on an event-to-event level while using her Twitter account to talk about a lot of other events happening in the city.

The week before the Mayor’s comments, a pedestrian was killed in Columbia City and the evening before a pedestrian was killed on Aurora Ave N—the same location of a pedestrian-involved serious injury collision the night after these comments. Frankly, the response from the Mayor was completely out-of-scale with the events happening on our streets every day.

Ultimately, the Mayor said that more money will help reverse the pedestrian safety crisis that Seattle is seeing on our streets, allowing her to bring the answer back to what is sure to become a signature achievement of her term: the sale of the Mercer Megablocks and the public benefit that will come from that sale.

But will more money move the needle? Or is it more likely that without a culture of taking traffic safety seriously for everyone in the city, particularly those in city government, that we will continue to see a lack of improvement?

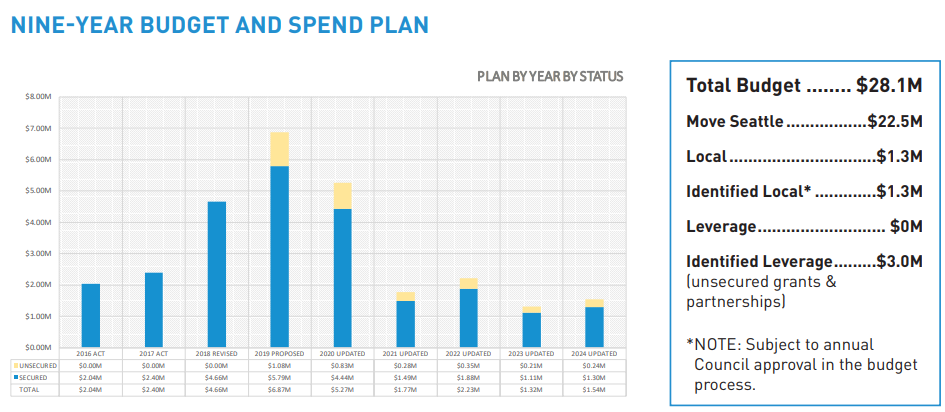

Move Seattle is the largest transportation levy in the city’s history, and it invests a lot of money in our transportation system, but it’s clear that dramatically improving safety is not the primary goal of the levy: maintaining the transportation status quo is. For the first few years of the levy, relatively up-to-date metrics on how Seattle was performing on reducing serious injuries and fatalities was available on the “Move Seattle Dashboard.” Now that metric is entirely missing from the Move Seattle levy page, with only the current year-to-date deliverables shown on the new dashboard.

Absent direct performance standards around Vision Zero, the biggest connection to making our streets safer in the levy is the Vision Zero Corridor program. The original commitment made to voters is 20 corridor-wide safety projects over nine years, which we are on track to exceed. But looking at what’s been accomplished at this near-halfway point, it’s hard to make the case that any of the projects are really making dramatic safety improvements, with the clear exception of NE 65th St. That multimodal street safety project, of course, would not have happened without advocates pushing it forward.

The others are not on that level at all: Beacon Ave S is listed as completed, even though possible protected bike lanes there were initially shelved completely and now are only planned through design. Fauntleroy Way is marked as done, even though the long-planned safety improvement through its busiest segment is still on hold pending Sound Transit 3 discussions. 24th Ave E in Montlake might be the saddest of the bunch, being marked as completed last year after no new pedestrian crossings were added and a proposed bus lane was eliminated—and the speed limit on the street was left at 30 mph when most drivers are traveling northbound at close to 40 mph.

The issue with the Vision Zero corridor isn’t necessarily a lack of funds, it’s a lack of aggressiveness of design changes, where more aggressive changes would not necessarily be more expensive.

Given the public safety emergency that the street safety crisis continues to be, one might also think that existing funds could also be diverted if needed. Consider the $8 million that the Levy Oversight committee just allocated for Neighborhood Street Fund projects. Data on which projects would serve crash-prone areas was available when making the final project selections but it was absolutely not one of the primary criteria.

Meanwhile, a 2016 Neighborhood Street Fund project that would have remade a crash-prone intersection on Beacon Hill remains on hold after neighborhood pushback essentially vetoed the project idea, even after it originated from leadership at a nearby middle school. Where is the department making the case that its projects will save lives?

Then there’s the prevailing push that has been seen in North American cities since the introduction of Vision Zero focusing on behavioral changes, primarily the behavior of the vulnerable users who are getting killed. From SDOT’s “Be Super Safe” to King County Metro’s “Walk Safe” to Sound Transit’s “Take Crosswalks Not Shortcuts” the idea seems to run very deep that getting people to change the behavior that bad designs enable is more effective than changing the design itself. And then there’s the particularly jarring new example appearing on posters and billboards in the Rainier Valley citing the very fact that Rainier Avenue is the most crash-prone street in the city as a reason to wear clothing that is more visible.

Paired with the absolute snail’s pace at which improvements on Rainier Avenue have come, the campaign represents this disconnect between improving bad design and changing behavior in a truly depressing fashion.

It seems unlikely that Seattle will be able reverse the alarming trends seen nationwide around traffic injuries and fatalities by continuing to do the same thing over and over again: advocacy campaigns and scattershot design changes specifically tailored to not upset too many people. Money alone will not change that broken formula.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.