Washington State’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) could not prove if the millions of dollars developers saved through Multifamily Family Tax Exemption (MFTE) have actually created a “net increase” in housing development across Washington State.

Multifamily Tax Exemption, better known by the acronym of MTFE, has been a cornerstone of Washington State housing policy for over a decade. What initially started out as a weapon in the fight against urban sprawl, morphed into one of the state’s largest generators, at least on paper, of affordable housing after a 2007 revision of the legislation allowed for developers building or rehabilitating multifamily buildings in urban centers to extend their eight year tax exemption to twelve years by designating twenty percent of their units as affordable to low or moderate income earners.

At first glance the numbers backing up MFTE as successful housing legislation appear impressive. Between 2007 and 2018, 424 developments throughout Washington State received MFTE exemption. 34,885 new units of housing were created, 21% of which were designated as affordable.

True to MFTE’s original goal of channeling growth back in urban areas, nearly half of developments receiving MFTE were created in Seattle alone, amounting to 17,432 units, 5,548 of them affordable, built or rehabbed during the same 11-year period. But 2007 to 2018 also represents a period of steady population growth in Washington State, and much of that growth has been focused in urban centers like Seattle. Since 2010, Seattle has added over a hundred thousand residents, making it one of the fastest growing cities in the US.

Thus the question of coincidence comes into play. Was MFTE smart housing policy that spurred multifamily development in urban areas, or did it amount to a tax gift for developers that would have likely built that housing anyway given the strong market?

The answer, provided by a recent report from the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC), is that no one knows. JLARC found that while developers have created housing using MFTE, it is “inconclusive whether this use represents a net increase in development.”

Basically, because of a lack of reporting and policy differences between cities, JLARC was unable to determine if the tax exemptions offered to developers through MFTE actually incentivized them to create more market rate or affordable housing than they would have without a tax exemption.

This is a big deal. MFTE was created in order to ensure the profitability of development in areas targeted for urban growth. To assess whether or not tax exemption actually provided enough of a financial reward to make previously dead-in-the-water development financially feasible, JLARC studied many different models, and in the process they discovered a wide degree of variance, enough that JLARC declared that “a definitive answer on feasibility is inclusive.”

Developers have saved millions in tax exemptions through MFTE and stand to save hundreds of millions more

In 2018 alone, beneficiaries of MFTE (i.e., developers and landlords who opted into the program) saved $19 million in state taxes and $61 million in local taxes. Projections completed by JLARC estimate that by 2023, the amount beneficiaries receive could balloon to $32 million in state taxes and $105 million in local taxes.

Over the past four years, an average of $1.1 billion in new property value became exempt each year through MFTE, and the amount of new property receiving tax exempt status through MFTE is expected to outpace expiring exemptions, JLARC said.

The value of a tax exemption also varies widely between jurisdictions. Statewide, JLARC found that for market rate developments, beneficiaries save an average of $2,096 per unit, per year for the life of the exemption. The amount was higher for developments that include affordable housing: beneficiaries save an average of $10,651 per affordable housing unit per year.

In Seattle, developers saved about $11,817 per unit. Because of local policy, all MFTE development in Seattle must include affordable units, which explains some of the higher-than-average savings.

These lost tax dollars have to be made up by other revenue sources. JLARC found that whether developers’ tax savings were shifted to other taxpayers or were simply forgone as revenue depended on factors that were individual to each development. However, overall, the report found that “some of the impact—both [tax] shift and loss—happens outside the cities granting exemptions,” meaning that nearby communities that have not implemented MFTE policies may still end up losing revenue.

What is MFTE’s impact on affordable housing?

Like many Seattleites, over the years I have personally known many working people who have benefited from affordable housing through MFTE. However, whether or not MFTE units designated as affordable are actually affordable to lower income earners has become questionable over the years. Moreover, the MFTE program doesn’t require landlords to check incomes again after a household initially qualifies, which means that household income could double or triple in subsequent years and the household would still be occupying a rent-restricted MFTE home.

Rents on affordable units in MFTE developments are pegged to area median income (AMI) and are identified as affordable to households classified either low-income (< 100% AMI) or moderate-income (typically 115%-150% AMI) earners. A “statutory maximum rental price” is determined from annual countywide AMI figures and other factors such as the size of the unit. Think for a moment about what countrywide AMI means in the context of King County: workers in Medina, Bellevue, and Redmond are all thrown in the same income index as workers in Kent, Tukwila, and Seattle.

As AMI has risen, rental costs have increased as well. The result is that in 2017, the most recent year JLARC was able to analyze, almost all statutory maximum rental prices for low-income households were higher than median market rent. Downtown Seattle, Downtown Tacoma, and Mercer Island were the only exceptions found in the state.

Rising AMI also has a cost increase effect on MFTE housing in nearby lower cost areas. Using 2017 figures, JLARC did an analysis on rental prices in King County. Using the model of a two-bedroom unit rented to a three member household, the consultants found that in some cases, like Auburn, the statutory maximum rent for a two-bedroom “affordable” MFTE unit was actually almost twice as expensive as median market rent for a two-bedroom unit.

Unlike affordable public housing offered through United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, in which rents are adjusted so that tenants pay no more than 30% of their monthly income on rent, MFTE rents remains the same for across qualifying households in different income brackets. Since most affordable units are designated for households earning up to 80% AMI, households that earn less may end up paying a greater percentage of their monthly income on housing.

Some cities, like Seattle, have opted for lower rent limits, a practice that JLARC supports. Overall, JLARC found that statutory rent limits in MFTE may not improve affordability for low- and moderate-income households. Even in Seattle, rising AMI and housing costs in general have driven up MFTE rental costs. Landlords have not faced limitations on rent increases, which has led to some landlords raising rents by over 10% annually. Mayor Durkan recently passed a 4.5% cap on MFTE rent increases, but it will only apply to new units.

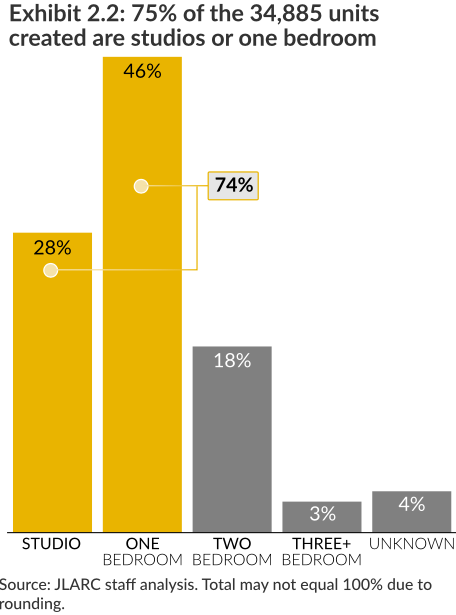

A final weak point for affordability is unit size. Although, the average household size in Washington State is 2.6 people, state law does not limit the type or size of units that may qualify for the MFTE program. About 75% of the units created between 2007 and 2018 are studios or one bedroom apartments. Some cities, including Seattle, have added additional requirements intended to incentivize the production of larger units, such as requiring deeper levels of affordable for SEDUs (small efficiency dwelling units) and increasing the amount of required affordable units in developments that do not have at least four larger (i.e., two-bedroom) units for every 100 units, but such policies appear to have had a negligible impact.

To determine how well MFTE is performing, better reporting is needed

As a whole JLARC’s report emphasized a broad need for better reporting and more accountability for jurisdictions using MFTE. Despite the requirement that jurisdictions report annually to the State Department of Commerce, JLARC found that “at least five cities have not submitted a report during the period reviewed, and at least 11 failed to report in one or more years.”

Additionally, most reports submitted by cities were incomplete and differences in calculations across reports made the overall data unreliable. As a result, JLARC found that the Washington State Department of Commerce “cannot provide reliable information about the number of exempt properties, the number of affordable units, the total value of exemptions granted, or other metrics listed in statute.”

Accountability is another weak spot. JLARC found that the current statute does not require cities to report data such as tenant incomes or household sizes that are needed to monitor the program or assess compliance with affordability requirements.

In order to determine if MFTE is worth millions of dollars in tax savings for developers, JLARC has made the following suggestions:

- The Legislature should require an analysis of profitability as a consideration for the exemption.

- The Washington State Department of Commerce should report annually to the Legislature on city compliance, the metrics in statute, and affordability measures.

- The Washington Stated Department of Revenue should report to the Legislature on which statutory ambiguities (i.e., instances where the policy can be interpreted in ways that go against its intent) require legislative changes.

At a time in which funding for affordable housing development and preservation is a critical need throughout the state, lawmakers should step up and demand better reporting and accountability on MFTE programs. The public cannot afford to lose hundreds of millions of tax dollars to incentives that have not proven their worth or that are so poorly calibrated that they aren’t achieving their mission.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.