On Monday, the Seattle City Council voted 6-1 in favor of a $9 million appropriation to continue work on the Center City Connector streetcar, with Councilmember Lisa Herbold casting the sole no vote. Councilmembers M. Lorena González and Kshama Sawant were absent. González was in Copenhagen taking urbanism classes, and Sawant walked away from the dais before the vote.

The appropriation, facilitated by an interagency loan, means that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) will continue engineering work making design tweaks needed to finalize the revised plan and break ground on the project, as we reported last week. The biggest change is bridge strengthening on Jackson Street to accommodate the new heavier CAF Urbos streetcars that will carry up to 166 people each and thus weigh about 40% more than the older model the City uses.

Previously slated to open in mid-2020, the project has been in limbo since Mayor Jenny Durkan hit the brakes in March 2018 as construction was ramping up, citing concerns about the budget. After nine months of review, she officially backed the project in January.

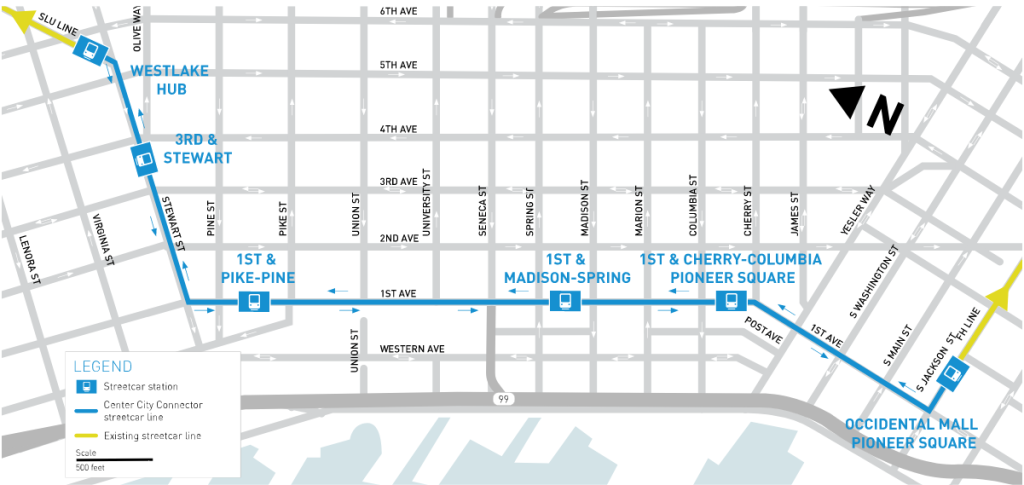

The Center City Connector will unite the First Hill Streetcar and South Lake Union Streetcar Lines to create one consolidated five-mile corridor. The new timeline has the Center City Streetcar opening in 2026, but SDOT will iron out the details in the final proposal it submits to the City Council sometime in the next year or two. Presently, SDOT’s portion of the budget sits at $208 million, with the $9 million approved Monday a portion of that, and utility work (attributed to Seattle Public Utilities or Seattle City Light) adding another $77 million.

“Today’s vote is another indication of growing confidence in this project and recognition of the need for clean and efficient transit in the heart of our city,” said Emily Mannetti, spokesperson for the Seattle Streetcar Coalition. “Record levels of people are living and working in downtown and we can’t afford further delay. We applaud the Mayor and City Council for moving the streetcar forward.”

Ahead of the vote, Councilmember Herbold delivered a lengthy soliloquy assailing the streetcar as a wellspring of all manner of evil. Many of the hits should be familiar by now, and most have been discredited in this publication.

Streetcars are transit workhorses not trinkets.

Herbold Claim: Streetcars are not real transit; they’re economic development tools.

Reality: The Center City Streetcar is a highly effective transit investment projected to boost streetcar ridership 230% so that the consolidated system would carry about 20,000 daily riders, which is more than any bus line in Seattle. In short, it’s real transit. And dedicated transit lanes on First Avenue means it will be fast and reliable. While Herbold painted it as a well established fact that streetcars are economic development tools not transit, in many cities streetcars are transit workhorses, as we’ve reported. We cited the example of Budapest which has more than a million rides per day on its streetcar network. Plenty more examples are out there, including Toronto with about half a million daily boardings.

20,000+ Daily Riders

Herbold Claim: The City’s streetcar ridership projections are suspect and likely grossly exaggerated.

Reality: SDOT used the ridership model required by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), which is based on fairly conservative assumptions. SDOT has yet to update the ridership projections for new 2026 target to open, meaning a nearly a decade of additional growth hasn’t been factored in. The First Hill Streetcar saw its ridership increase 31% in 2018. The numbers on the South Lake Union Streetcar aren’t good, but that line is only 1.3 miles long and is very unreliable. People seem to be walking or taking more frequent buses instead, which benefit from the same transit lanes the streetcar uses on Westlake Avenue. The Center City Connector project will fix that by making a five-mile corridor with dedicated transit lanes through Downtown Seattle and higher frequencies.

Small businesses benefit

Herbold Claim: Only undeserving big businesses would benefit. Streetcar construction would irreparably harm small businesses.

Reality: Many small businesses have joined the Seattle Streetcar Coalition and testified at council meetings that they want the streetcar project and expect it to greatly boost business. Chinatown-International District business owners have pointed out that the direct connection to Pike Place Market will make it easier to attract tourists to the area. Moreover, it was promised to Chinatown-International District and First Hill business owners and residents who accepted the disruption caused by First Hill Streetcar construction.

Still well positioned for $75 million in FTA grants

Herbold Claim: SDOT won’t be able to collect the Small Starts grant from the federal government.

Reality: Seattle already secured a Small Starts grant based on the strength of its proposal. If the delay forces the City to reapply, the case will still be very strong thanks to high ridership figures–likely even higher than before due to Seattle’s growth. If the Center City Connector cannot get a Small Start grant, virtually every transit project in the region is in jeopardy because the Center City Connector had higher ridership than any other similarly-sized project.

False scarcity

Herbold Claim: The streetcar steals from other transit projects.

Reality: Most of the streetcar budget isn’t fungible or transferable. Moreover, there’s no need for a scarcity mentality for crucial transit projects. Seattle has a plethora of transportation funding possibilities, including: the Seattle Transportation Benefit District (which has a renewal coming up soon), ridehailing fees, decongestion pricing, transportation impact fees, or the Monorail taxing authority. Of the $285 million total project budget, including utility costs, only $100 million is recoverable, SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe said. Meanwhile, the West Seattle Link Extension tunneling option that Councilmember Herbold supports (it’s in her district) would cost an extra $700 million, Sound Transit says, while increasing ridership a negligible amount over elevated rail options–1,000 to 2,000 daily boardings.

High farebox recovery ratio

Herbold Claim: The streetcar needs a really big operational subsidy.

Reality: Virtually every transportation mode requires a subsidy. Roads are not free to pave and maintain. Cars externalize their costs on the environment and society through the many forms of pollution they create. The operational subsidy the streetcar is projected to require will be relatively small. King County Metro buses recover about 27% of their operational costs on average, also known as the farebox recovery ratio. Meanwhile, the streetcar already recovers operational costs at a higher rate, and the independent consultant review that Mayor Durkan requested found that, with the Center City Connector, the farebox recovery ratio increases dramatically to 52%–twice Metro’s average bus line. In fact, in upper-end ridership scenarios with good advertising deals, the streetcar may come close to covering its own operational costs. Of course, we could also make transit fare-free and pay for operations through taxes if boosting transit ridership, promoting equity, and lowering climate emissions were our primary goals.

What’s next

With the appropriation SDOT will get to work getting the streetcar project ready to relaunch. Once the additional engineering and design work is complete, the agency will need to bring another proposal before council to close the project’s budget shortfall, currently estimated at $65 million.

It was a busy day at Seattle City Council on Monday with the council also passing a Seattle Green New Deal resolution and overriding Mayor Durkan’s veto in order to keep the city’s sweetened beverage tax dedicated to healthy-foods programs as intended and promised by the legislation.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.