In the first six months of 2019, someone was seriously injured or killed on Seattle’s streets at an average rate of once every 44 hours, the highest number in almost a decade. This week Michelle Baruchman at The Seattle Times was the first to obtain the data showing that between January 1 and June 30 Seattle saw 98 traffic collisions that resulted in serious injury or loss of life of 101 people. Even more alarming still is the rate at which pedestrians getting seriously hurt continues to climb.

Serious injury collisions involving people walking have continued to climb at the fastest rate of any collision type, with 37 pedestrians seriously injured in six months and two fatalities: one Downtown on Columbia Street in January and one on Lake City Way NE in February. This does not include the death of a woman on SW Barton Street in West Seattle that happened in early July.

Data from past years shows that there are consistently more collisions in the second half of the year than in the first. 39 pedestrians injured or killed in 180 days means that the city is on track, unless there is a wild variation from past years, to see around 90 pedestrians seriously injured or killed by the end of 2019. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) still has not released the number of serious injuries of pedestrians in 2018 (there were 10 fatalities) but those 2019 numbers point toward a big jump compared to the 2017 number of 73, which was itself the largest number going back to at least 2005. For much of the previous decade, the number had hovered around 50.

Seattle is on track to see 90 pedestrians seriously injured or killed on its streets if current trends continue. (2018 information still has not been released by SDOT) (Graphic by the author)

The trends so far for collisions involving people on bikes are also alarming, with 14 people seriously injured and one person biking across Rainier Avenue killed in February. Trends from past years suggest that the city could see around 35 to 40 people biking seriously injured or killed by the end of the year, another cause for serious alarm.

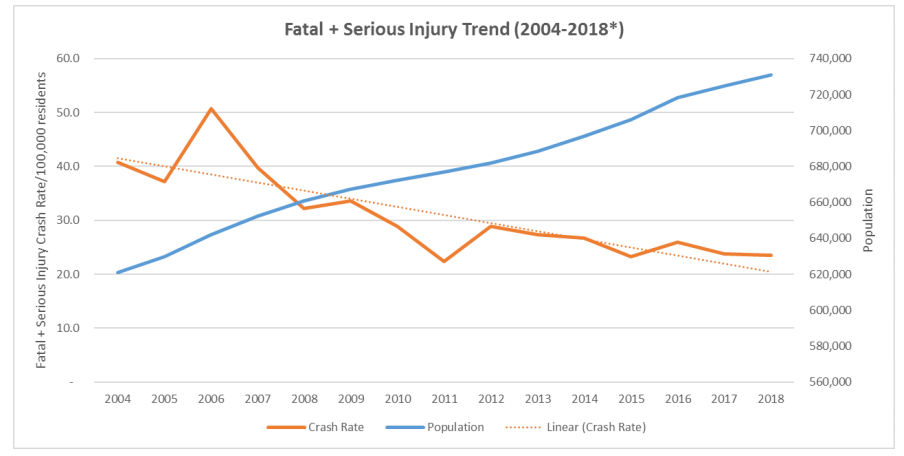

This sharp uptick comes in contrast with the message coming from SDOT whenever it presents data on its Vision Zero traffic safety program, that Seattle is headed in the right track on safety. In 2015, the City of Seattle adopted a “vision zero” goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2030. In March, the Vision Zero team went before the Sustainability and Transportation committee and told city councilmembers that “despite massive growth, Seattle continues to be on the right track.” They did not present specific data on pedestrian safety. While it’s true Seattle has grown a lot, zero can’t be population-adjusted.

While SDOT officials have sought to placate the city council, Mayor Jenny Durkan, on the other hand, has not publicly committed her administration to the goal of zero serious injuries or fatalities on Seattle’s streets by 2030. Despite having a Vision Zero team at SDOT, it’s not clear that goal is still in force. The examples that suggest the city prioritizes other things are myriad.

The most famous regression on making Seattle’s streets safer during the Durkan administation was 35th Ave NE, which SDOT is still arguing is in line with vision zero goals. Bike lanes on N 40th St were also eliminated from consideration. Rechanneling any additional segment of 35th Ave SW in West Seattle was taken off the table with little explanation. Another key safety project along Fauntleroy Way SW was shelved. “Vision Zero corridors” like 24th Ave in Montlake were completed with barely a sprinkling of safety improvements. And adaptive traffic signals have made pedestrian waits worse and encouraged crossing against the signal. The list goes on and on.

The most positive advance in pedestrian safety that the city can point to is the deployment of Leading Pedestrian Intervals. To install an LPI all the city has to do is set the walk signal to come on a few seconds ahead of the green light. Fewer changes impact motorists less than doing this, with many signals across town adding extra time at the end of the cycle for vehicles to get through the intersection. But the safety impact of LPIs is hindered with free right-on-red turns: Seattle moved forward with increasing right-on-red restrictions downtown in 2015 but stopped after doing a few intersections. Contrast with Washington, D.C. restricting right-on-red at 100 intersections just this year.

To ensure that pedestrian injuries actually start reversing, we are going to need to do more than give people walking a head start. We’re going to need to fully separate pedestrian movements at intersections, particularly in urban villages and centers, and dramatically reduce the amount of available space drivers are able to use to get up to unsafe speeds.

The city’s own Bike and Pedestrian safety analysis, completed in 2016, analyzed common pedestrian crash types and locations. Now, SDOT is working on a new version that includes more variables like protected bike lane locations. But there’s very little evidence that the department has taken a proactive approach to the data it learned from the report by tackling intersections with high crash rates. Just look at Denny and Stewart. Portland is a model for this, with its “high crash network” program that identifies problematic corridors and tackles them one by one.

2019 marks four years since Seattle signed on to Vision Zero, and things have gotten worse, not better. It’s absolutely apparent that Seattle’s leaders are not taking the pedestrian safety crisis seriously enough. While the steady increase in people walking getting hurt might not be as galvanizing an event as the scaling back of the bicycle master plan, it’s time to make it clear that the Mayor’s apathy toward the issue is unacceptable.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.