The Seattle City Council voted 8-0 Monday to pass accessory dwelling unit (ADU) reform, making it much easier to add a backyard cottage and/or an attached in-law apartment in a single family lot. The bill included a single family home size limit– colloquially known as a McMansion ban–that will limit new construction to no more than 2,500 square feet on 5,000 square-foot lots. The limit is a bit more generous on larger lots since it’s set at half the square footage of lot.

The City projects the changes will lead to more than 2,400 additional homes over the next decade, while decreasing the rate of tear downs of homes. That is beyond the nearly 2,000 ADUs already expected under existing rules in the next ten years.

While a modest step to add housing options and increase density in single family zones, this still represented a big win for housing advocates who had to overcome multiple appeals from deep-pocketed homeowner groups led by Queen Anne Community Council and Marty Kaplan that stalled ADU reform in 2015. Those delays meant that Tacoma ended up leading on backyard cottages before Seattle did.

The timing also worked out that Seattle’s ADU win was overshadowed by more dramatic action by the Oregon State Legislature, which voted Sunday to allow fourplexes throughout Portland and other large cities in the state, with duplexes permitted throughout mid-sized cities. Oregon took the torch from Minneapolis, which passed a reform to allow triplexes throughout its single family zones, and one upped them and went even farther by crucially not letting suburbs off the hook.

We’ve seen that many suburbs are slacking when it comes to permitting more density and undoing exclusionary apartment bans. The Washington State Legislature weighed the issue last session but ultimately couldn’t agree on widespread reform of single family zoning. Maybe with Oregon’s good example, next session will be different.

For now, we have much more permissive accessory dwelling unit rules to content ourselves in Seattle. Supporters, nonetheless, were quick to point out more work remains to be done. More Options for Accessory Residences (MOAR) is a pro-ADU group formed to push the legislation. MOAR member Matt Hutchins, whose architecture firm designs backyard cottages, didn’t paint the legislation as a cure-all. “This is not a silver bullet that’s going to solve the housing affordability crisis on its own,” Hutchins said. “But it is another potential option and that’s what we need.”

Seattle has grown at breakneck speed, going from 608,660 residents in the 2010 census to nearly 750,000 residents in the state’s recent estimate. That pace has made Seattle the fastest growing big city of the decade, but even in the midst of that boom some single family neighborhoods are shrinking as household sizes decrease and apartment bans persist. ADU reform should allow some gradual growth in these exclusive neighborhoods and modestly rectify Seattle’s uneven growth pattern. Urban Villages and Urban Centers, despite occupying a small fraction of Seattle’s land, have taken 85% of recent construction.

“We must allow new neighbors renters to live in every single neighborhood in our city,” said Laura Loe of MOAR and Share The Cities in her public testimony. “This is the only way right now to deal with the apartment bans in 81% of our city according to recent maps from the New York Times.”

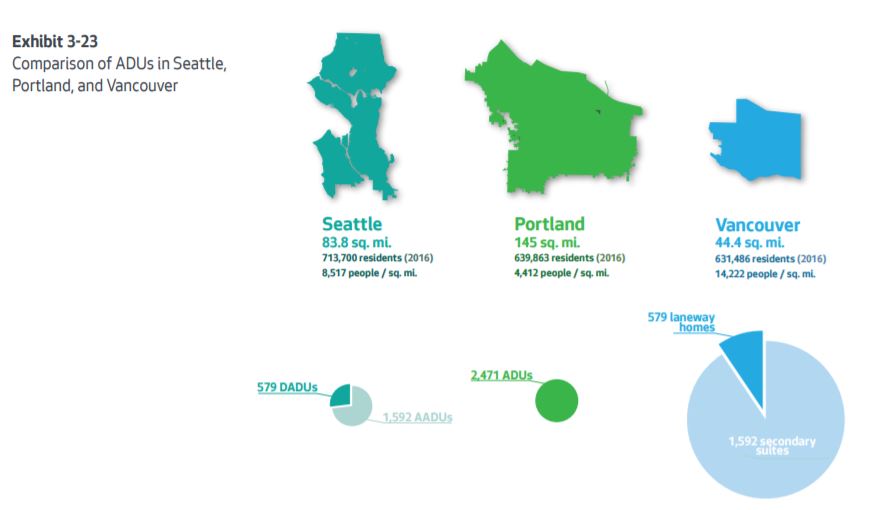

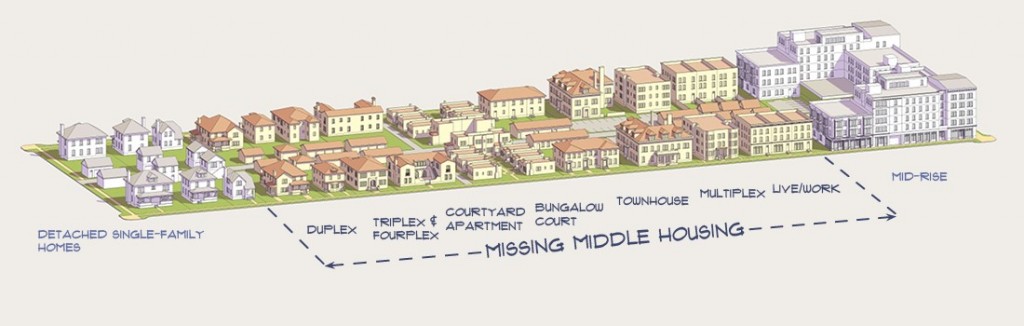

The prevalence of single family zoning has made new missing middle housing rare–housing types like backyard cottages, in-law apartments, duplexes, and small apartment buildings.

“We haven’t had a lot of housing choices in the last 20 years,” Hutchins added. “It’s either big apartment [buildings] or unaffordable single-family houses.”

Environmentalist think tank Sightline Institute supported the legislation and successfully advocated to keep owner occupancy and parking requirements out of the package. Upon passage, Sightline declared Seattle’s ADU policy as “best in the nation” and linked it to climate action.

“This puts Seattle at the forefront of progressive ADU policy in the nation, confirming Seattle as a leader in progressive ADU policy,” said Margaret Moreales, Sightline’s housing policy researcher. “This is just the beginning of reimagining our cities as inclusive, green, and affordable spaces. These changes will permit more of the very types of housing Seattle needs as it stares down both a climate and an affordability crisis.”

Councilmember Lisa Herbold worried of a speculative bubble due to the lack of occupancy requirements to add ADUs and proposed an amendment adding them. However, Councilmember Kshama Sawant squashed this idea: “I have not seen any speculative ADU bubble anywhere.” The amendment failed.

Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda cheered passage of ADU reform but pointed to work ahead.

“By reducing barriers to more diverse housing choices across the city, we can right historic wrongs that led to exclusionary zoning in our neighborhoods and correct course to advance a greener, denser, and more affordable Seattle,” said Councilmember Mosqueda, who has directed City Staff to conduct a racial equity toolkit on Seattle’s Urban Village growth strategy.

That equity effort could conceivably lead to allowing fourplexes on all residential lots or adding more urban villages in a Comprehensive Plan update. With a victory to point to, housing advocates are feeling a sense of momentum.

“ADUs and DADUs provide opportunities for multigenerational housing, help us decrease our environmental and carbon footprint, and provide some homeowners with a way to stay in their homes and age in place—an important benefit as the cost of living rises in Seattle,” Mosqueda concluded. “This is one meaningful step that will generate gentle infill housing options, but much more must be done to create the density we need to accommodate our growing city.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.