Suburbs surrounding Seattle, some of them literally islands, are pulling up the drawbridges to growth. That is putting even more pressure on Seattle to shoulder the load for the entire metropolitan region, and it’s making the window for affordable housing solutions even narrower.

Bainbridge Island has had a moratorium on most new development since January 2018. Since 2009, Bainbridge had added residences at the “breakneck” pace of 66 per year and local home prices have continued to rise. This prompted several Bainbridge City Councilmembers to exclaim supply and demand does not work–at least not in Bainbridge! Do you expect them to add more than 66 homes per year?

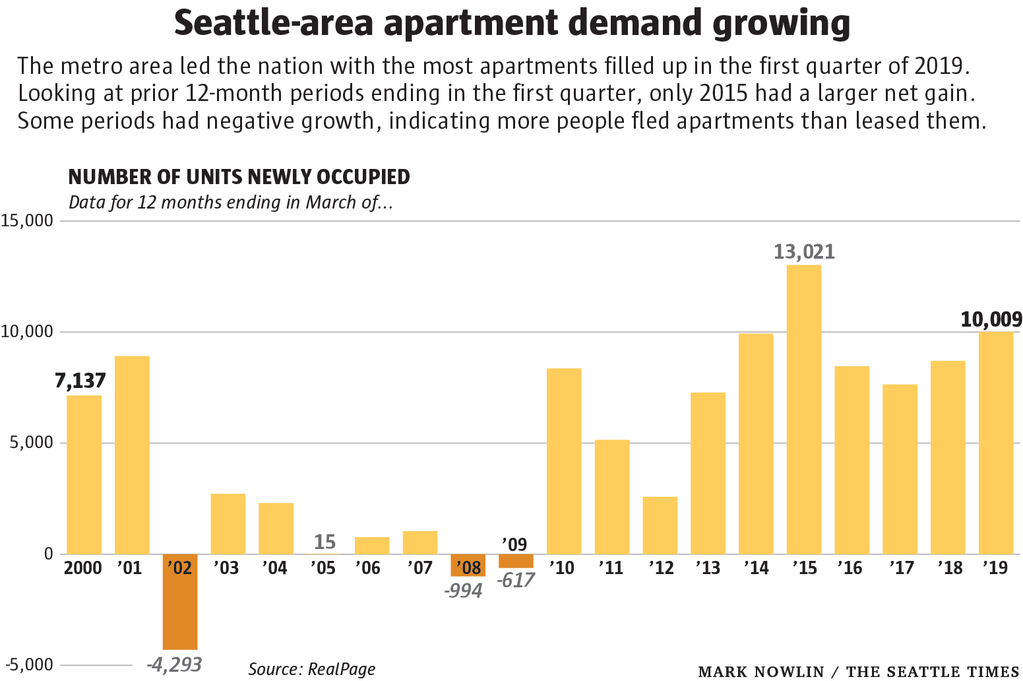

In the same timespan, Seattle has added more than 50,000 apartments and well over 100,000 new residents.

Mercer Island froze development in 2015 and even with the ban technically lifted, it may be easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than an apartment building to earn a building permit in Mercer Island. The offering of a development site near Mercer Island’s future light station station (set to open in 2023) could be the rare exception to that rule. Incidentally, Mercer Island is the residence of Seattle Times publisher Frank Blethen, who’s turned his paper’s opinion section into a megaphone for apartment bans–that is preserving single-family housing, neighborhood character, and civilization as we know it.

Sammamish had a year-long moratorium that it partially lifted in September 2018, although the City ironically extended the building ban in Sammamish’s “Town Center”–supposedly the community’s mixed-use focal point. The Sammamish City Council enacted “Neighborhood Character” restrictions like a doubling of building setbacks that will shrink and discourage new development, not to mention a concurrency requirement linking density to wider roads.

The Issaquah City Council passed a citywide moratorium on apartment development in September 2016 following uproar over a large new apartment building. Issaquah councilmembers said their decision was motivated by a desire to encourage more density, improve urban design, and calibrate affordability requirements.

“Get rid of single-story, 1980s suburban retail and replace it with multi-story, denser projects that will accommodate growth and create a more vibrant part of the city in central Issaquah — that’s what [city leaders] wanted, but we weren’t necessarily getting that,” said Issaquah Development Director Keith Niven in a Crosscut interview.

But, to the region, even moratoriums with good intentions end up meaning less housing gets built and more pressure is put on everyone else–and ultimately Seattle given the trend.

Issaquah lifted the citywide moratorium in March 2017, but extended the ban in central Issaquah (where apartments were being funneled anyway) to continue tinkering with the development standards and “get it right.” Finally the City lifted the ban completely in May 2018 and released new development guidelines. Admirably, Issaquah has a urbanist vision for its downtown (big plans for the central district helped the city lobby for its own Link light rail line in the Sound Transit 3 package.) However, the 20-month moratorium seems to have taken the wind out the sails of the little development boom Issaquah had been having. Post-moratorium, no major projects have materialized yet.

Federal Way issued an “emergency” one-year apartment ban in June 2016, citing crowded schools. Even when the ban was lifted, Federal Way policymakers used exceptionally high impact fees on apartments–raising them seven-fold to more than $20,000 per unit while leaving single family fees as is–to effectively continue the ban. Public outcry made it clear a loud minority of residents resented apartments and associated them with crime. Federal Way City Council came through with code changes upping parking requirements, reducing building massing, limiting building heights, and increasing setbacks–all seemingly intended to zone new apartments out of existence.

The state legislature considered legislation outlawing impact fees targeting apartments for higher rates than single-family homes, which would have challenged Federal Way’s practice. However, that stipulation was left on the cutting room floor as a more stripped down version of House Bill 1923 passed. Regardless, Federal Way’s code changes may have been sufficient to discourage new apartments exorbitant impact fees or not–or the City may have just invented new obstacles. Federal Way will get a light rail station in 2024, but transit-oriented development prospects aren’t looking great.

The spate of moratoriums and downzonings jeopardized on the Growth Management Act, which only allows moratoriums in emergency circumstances. Recent history suggests emergencies are now pretty commonplace in suburban communities. The intent of growth management was to encourage growth in existing communities rather than pushing it out to the unincorporated areas where it’d encroach on farmland, forests, and wilderness areas while requiring expensive new infrastructure and larger climate footprints. Instead, unincorporated Snohomish County and Pierce County seems to be filling the housing vacuum as suburbs shirk their responsibility.

Some Targeted Suburban Upzones

Some suburban cities are taking measures to encourage growth. Everett rezoned its core to allow some highrises. Edmonds upzoned along SR-99; although, its downtown upzone was scuttled out of desire to preserve the views of hilltop single-family homes. Shoreline rezoned neighborhoods adjoining light rail stations coming online in 2024. Mountlake Terrace is rezoning to allow 12-story buildings adjacent to its future light rail station (again 2024), but is generally preserving single-family zoning everywhere else–a common story.

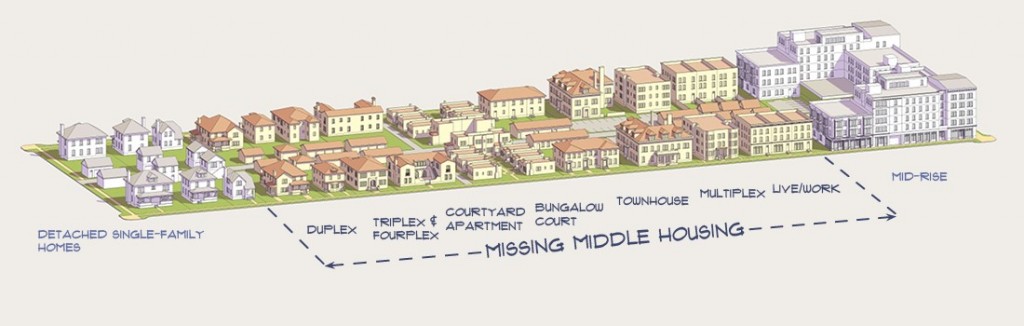

While providing highrise zoning is a promising sign, the question remains of whether developers will take advantage of it. Lenders may look at large expensive projects in unproven markets as risky investments. Proximity to light rail could be nice selling point that ends up getting big projects built. However, there are plenty of places that are just a little a bit farther from bus rapid transit or future light rail stations that could see missing middle housing typologies (like triplexes, rowhouses, and courtyard apartment buildings). Only they aren’t zoned for it. Restrictive single-family zoning continues to hem in the urban districts. Seattle’s problem is the same problem regionwide.

Opposition to Low-Income Housing

Other suburbs are seemingly pro-growth, but not when it comes to low-income housing.

The Lynnwood City Council is blocking a public housing redevelopment just off its Swift Blue bus rapid transit line on SR-99. Lynnwood had been making waves for its vision for mixed-use midrise development and residential highrise in its new “city center” around its future Link light rail station (set to open in 2024). If the Lynnwood City Council has turned against low-income housing, that could be a bad sign for those that had hoped Lynnwood City Center could prove a release valve for working class folks priced out of Seattle and the Eastside.

Bellevue gets accolades for allowing 60-story towers in its playground for the rich downtown and props for its midrise mixed-use corporate office park at the Spring District. However, when it comes to siting a homeless shelter rather than a corporate campus, Bellevue wasn’t so generous. A nonprofit has been trying to build a homeless shelter since 2014 and is looking at a 2022 opening best case scenario as neighborhood after neighborhood has turned them away, whether by direct opposition or the prevalence of single family zoning. Moreover, “Bellevue’s housing stock overall is growing at about half its historical average,” Mike Rosenberg pointed out, even with some splashy towers going up.

Most of the Eastside shares the sentiment with not many shelters to begin with and only a trickle of new capacity since the region’s homelessness crisis worsened in the past decade. There are a few promising signs after years of inaction. For example, Kirkland is set to get its first ever permanent 24-hour homeless shelter in the year of 2020.

Seattle Is Facing Housing Obstruction Too

Pointing out that suburbs have been sandbagging growth isn’t to let Seattle off the hook. Seattle’s designated urban villages have grown remarkably rapidly, carrying 85% of the city’s new housing growth. Meanwhile, the pace of growth in Seattle’s single-family zones has been tepid. Some single-family-dominated neighborhoods have seen their populations shrink in recent decades as household sizes decrease and no new housing goes in.

Even fighting with a hand tied behind its back, Seattle has done well, leading the region in growth and adding more than 130,000 new residents since the city’s 2010 census figure came in at 608,660 to something like 750,000 residents today. Even so, the narrative many Washington lawmakers continues to push is that Seattle, by obstructing housing and not growing faster than it is, is ruining everything–which is a well-worn narrative and pretty misleading in this case. Sen. Guy Palumbo (D-Maltby) is one state legislator known to use the narrative and his colleague Sen. Joe Fitzgibbon (D-Burien) pointed out one hole in “Seattle is to blame” line; namely, that most suburbs have just as much (if not more) single family zoning as Seattle does.

Seattle Is Building Much Faster than the Suburbs

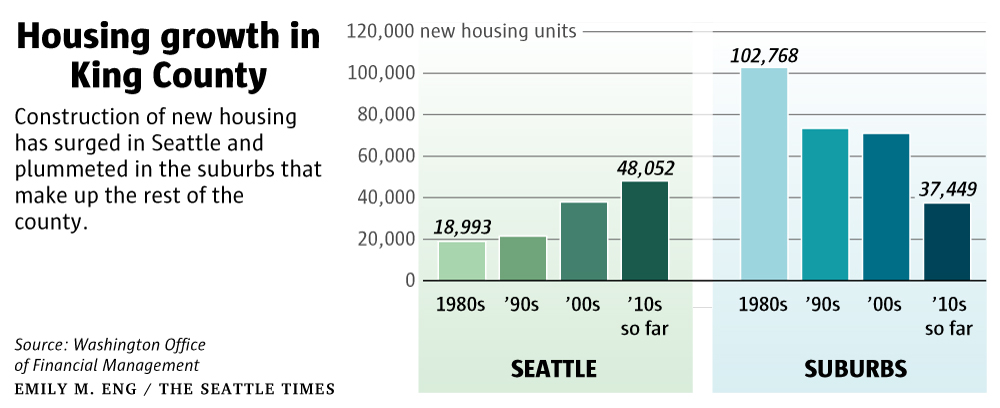

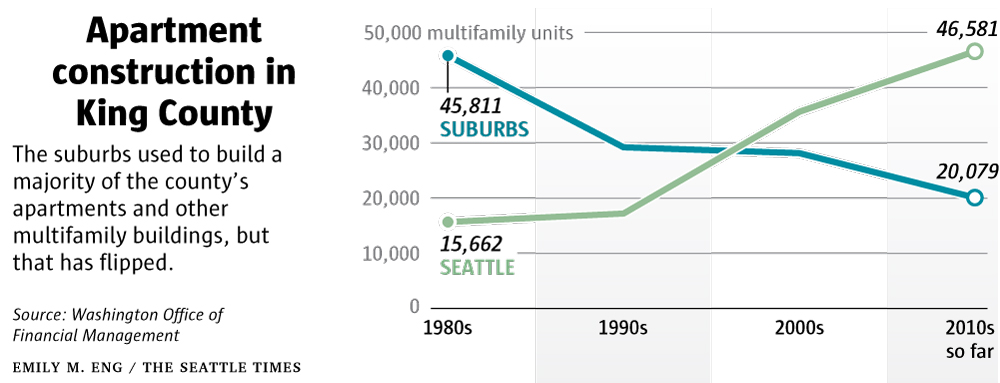

Seattle–even with some egregious examples of NIMBY hijinx–is growing much faster than the suburbs. Housing obstruction in the suburbs paired with a trend toward walkable urban housing has nearly ground to a halt multifamily housing growth in the suburban cities. Seattle Times real estate reporter Mike Rosenberg reported on the slow growth suburbs phenomenon in August 2018:

Right now, Seattle has 62 percent of all the apartments under construction in King County, according to Apartment Insights/Real Data, which tracks construction and planning of buildings with at least 50 units. In the county’s suburbs, Redmond and Bellevue host more than half the apartments underway now.

But looking farther into the future, the forecast calls for an even stronger divergence: Seattle has 82 percent of all the apartments planned but not yet under construction in King County, among large buildings. Actually, there are more apartments planned in the core of downtown Seattle than in all of the county’s suburbs combined.

Not all of those units will get built, but still – Seattle has nearly 28,000 apartments in the pipeline, while all the suburbs combined have about 6,000 planned, among large buildings.

It’s hard to explain away such a reversal in growth between Seattle and the suburbs. Certainly urban living is “in” right now and Seattle does have Amazon and other major employers drawing people inward. Still, clearly there’s demand to live in communities all across the Puget Sound region and people might live in those places if there were more housing options. It’s just that Seattle is doing a lot more to meet that demand than anywhere else and it’s not even close.

While some believe markets are very efficient at meeting demand, housing markets are pretty complicated. The 2008 Housing Crisis dried up the development pipeline and drove a good number of construction contractors and developers out of business–especially those overinvested in exurban McMansions. Since the crash, developers may have overcorrected abandoning suburban projects to get in on the action in Seattle, where Amazon had rapidly added 45,000 high-paying jobs. The hoops, hurdles, and moratoriums developers are being forced to jump through in some suburbs may have helped make their mind up.

The market had been really good at building suburban sprawl until the 2008 crash. In the 1980s, the suburbs outproduces housing five times over, adding 102,768 as Seattle added less than 19,000. Now, that suburban sprawl is choking growth. Suburbanites are using big-lot single-family zoning, development moratoriums, exorbitant impact fees, parking requirements, setback requirements, and whatever else they can throw at projects to keep their neighborhoods from growing.

Perhaps we need a state or regional body to take more control of zoning and land use restrictions, promoting missing middle housing expansively within the urban growth boundary. We also might need a major investment in social housing to ensure that residential towers go up in places like Everett and Lynnwood that want them but might not be attractive targets for global real estate capital any time soon.

The featured image is credited to Seco Development and shows the Southport complex in Renton.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.