From mega developments like the Collective in London, to more boutique spaces like Euclid Manor in Oakland, co-living is increasing its influence on housing markets across the globe. As the trend arrives in Seattle, developers are paying attention.

Last year the health service company Cigna released the results of a survey on loneliness and social isolation in the USA. The results were striking. About half of Americans reported sometimes or always experiencing feelings of loneliness. Often associated with older adults, loneliness has trickled down through ages, afflicting Americans in all phases of life, the young in particular. Millennials and Generation Z report higher levels of loneliness than previous generations; Generation Z, which includes young adults aged 18-22, has been described as the “loneliest generation.”

Significantly, what former US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has called a “loneliness epidemic,” is on the rise among people of all walks of life; In the last fifty years, regardless of geographic location, gender, race, or ethnicity, rates of loneliness have doubled in the United States.

The pervasiveness of modern loneliness has led researchers to speculate on its root causes. Not surprisingly modern trends in urban planning and architecture have been implicated as contributing to the rise of social isolation.

“If we had deliberately aimed to make cities that create loneliness we could hardly have been more successful,” said Suzanne Lennard, an architect and the director of the International Making Cities Livable movement, in the 2018 Vice article, Our Cities Are Designed for Loneliness.

According to Lennard, sprawling suburban style developments that prioritize private over shared space is a major contributor today’s loneliness epidemic. Others have rightfully noted that suburbs are not just to blame. Even within cities like Seattle, loneliness can be a fact of life. In her article, Why A City Block Can Be One Of The Loneliest Places on Earth, Eve Williams pointed out that after a few months of living in her first solo apartment in Downtown Seattle, she had yet to hold a conversation that went beyond “hello” with one of her neighbors and she had never even seen the other. “The tenant could be a human-sized badger — I have no idea,” said Williams.

Between 2012 and 2017, studio and one bedroom apartments made up about 80% of all multifamily housing built in Seattle. In some neighborhoods the trend has been even more pronounced than others. For example, in Ballard 72% of new apartments constructed in that timeframe were studios.

These statistics make me think of an observation an acquaintance made one recent evening as we were leaving a meeting. “We’re all in such a hurry to go sit alone in our little apartments,” she said, sagely calling out what feels like a truism of modern life: Our environment may engender proximity, but not engagement. For many people, it is often more comfortable to sit in a cafe and stare at a screen than to chat with a stranger. The norm has become to be alone together.

Some architects and designers believe that the situation is bound to change. In her article, Co-living 2030: Are you ready for the sharing economy? Hannah Wood put forth an interesting speculation. “Perhaps new shared ways of living are overdue in our digital age, and co-living will enter the rental housing sector as co-work spaces have transformed the nature of the traditional office.”

Can we design our way out of the loneliness epidemic?

Through urban planning and architectural blunders, we may have designed at least part of our way into the current loneliness epidemic. The good news is that we also may be able to design our way out of it.

Co-living, broadly defined as when residents share living space, comes in many different forms around the world. In the US, it is often associated with people in their twenties sharing housing with roommates. Generally, it is seen as a temporary arrangement; a stepping stone between leaving the family nest and embarking on a fully fledged adult life in a private home.

But with today’s stagnant salaries and surging housing costs, co-living has become more than a temporary arrangement. Co-living is evolving in a multi-billion dollar industry, one that is poised to make an impact on built environments the world over, including in Seattle, where developers large and small alike are paying heed to this growing trend.

While most co-living companies focus on the management of existing properties, a few are embarking on designing and building their own developments or acquiring properties that were built specifically as co-living developments. These companies believe that co-living investments will be more successful, and profitable, if they are created from the bottom up with the intention of being group living environments. It is a bit like the intentional communities of past, except the intention mostly is found on the design side of things. Advertising for these developments focuses on aesthetics, comfort, and even luxury. As one person put it, today’s co-living is for hipsters, not hippies.

New co-living developments are coming to Seattle

When I first heard about early design guidance (EDG) being sought for a multi-family development designed as a co-living space in the Central District earlier this year, I was not aware that commercialized co-living had taken off in such as big way. In fact, I was curious to learn why developer Kamiak had chosen build a co-living site rather than the more conventional studio and one bedroom apartments.

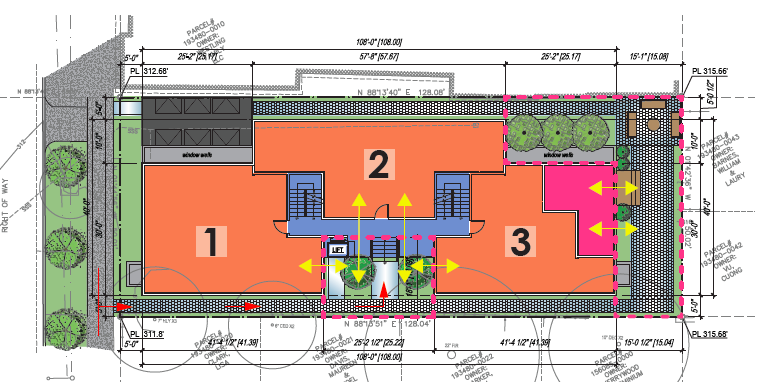

Kamiak has included co-living units within the designs of other projects they have in the works, but the Central District develop will be their first venture into building space fully designed for co-living. The four-story building will include 15 apartment units, each consisting of three to five bedrooms, which each have their own private bathroom. Apartments also have a shared kitchen, washer/dryer, and living/dining room. On the ground level, a co-working space will open up into a 1,300 square foot garden area.

Owner Scott Lien took time to speak with me about why the firm has decided to invest in a co-living development. While he has hopes that the development will be successful, he admitted that it was “a little more risky financially than a standard apartment development” because the product is less common to the market. However, Lien’s business partner has experience developing co-living sites in other parts of the country and felt like the location was right for co-living.

Additionally, according to Lien, when co-living takes off, it can be a more stable investment than a conventional multi-family development. He cited research that show people who live in co-living developments tend to stay there longer, two and a half years on average, than they do in conventional apartments.

Lien also cited the desire to create community among residents as one of his aims. “When you live in a studio your interactions are limited,” Lien said, “But with co-living you have roommates and can establish a sense of community early on.”

Lien plans to have Common, one of largest co-living companies, manage the property for about ten years before it is sold. At the time it is sold, it could continue as a co-living site or be repurposed into family size housing. Because of the development’s flexible design, “a buyer might decide to go a different direction in the future,” Lien said.

While Lien’s goal is to make rental prices a bit more affordable than rent of a studio apartment ($1,000-$1,300), not all commercial co-living provides cost savings. In addition to promoting luxurious environments, companies also provide amenities like weekly cleaning service, basic groceries, and recreational activities for residents. Lifestyle rather than affordability is the product promoted.

Commercial co-living first got its start with Silicon Valley hacker houses, and it some ways many of the developments have not moved far away from the model. Advertising often showcases a “digital nomad” life, which usually means a young adult with laptop in hand. While a promotional co-living photo with a dog or cat occasionally makes its way in, children are not to be found. While Lien said it would be possible for families with children to live in one of his co-living developments, it is clear that as of yet the model is heavily focused on meeting the needs and desires of adults without children.

Nevertheless, in the long run architect Claire Flurin has high hopes for the developer model of co-living being created by companies like Kamiak. In her point of view, it will help bring shared housing into the mainstream and make it a standard of part of our urban landscape’s housing types. Hopefully, this would broaden the range of co-living options so that more people are able to take advantage of its social benefits.

It will be years before Kamiak’s co-living development is completed. For those who interested in trying out this type of co-living, Common is already managing two Seattle properties, one in Capitol Hill and another in First Hill. And if work is your perfect remedy for loneliness, WeLive, an offshoot of WeWork, is constructing a 36 floor mixed use co-living development in downtown Seattle. Complete with “high-speed Wi-Fi and all of the coffee, tea and beer you can drink,” the building, is supposed to be move-in ready in 2020.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.