Multimodal corridors are intended to reduce automobile dependence by integrating rapid transit into existing freeway infrastructure. However, designing transit around freeways can make it difficult to veer from car-centric habits.

The current N 145th Street corridor that divides Seattle from Shoreline is dominated by automobile traffic. About 30,000 vehicles crowd into the corridor daily, leaving little space on the road for other modes of transportation.

As a result, narrow sidewalks tightly hug the road and are decorated with warning signs for wheelchair users and would-be street crossers. No bike lanes, not even sharrows, indicate that cars should share space with bikes. Buses navigate congestion, while bus riders wait at stops that squeeze them close to traffic.

Dangerous conditions on 145th Street for pedestrians, transit users, and cyclists

Photos by author

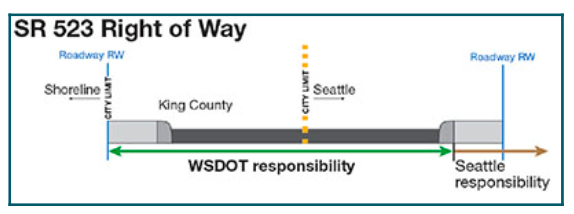

Jurisdictional oversight is also a major problem. Running along the border of Seattle and Shoreline, N 145th St is shared by both cities and part of the land that runs beneath it is technically part of unincorporated King County.

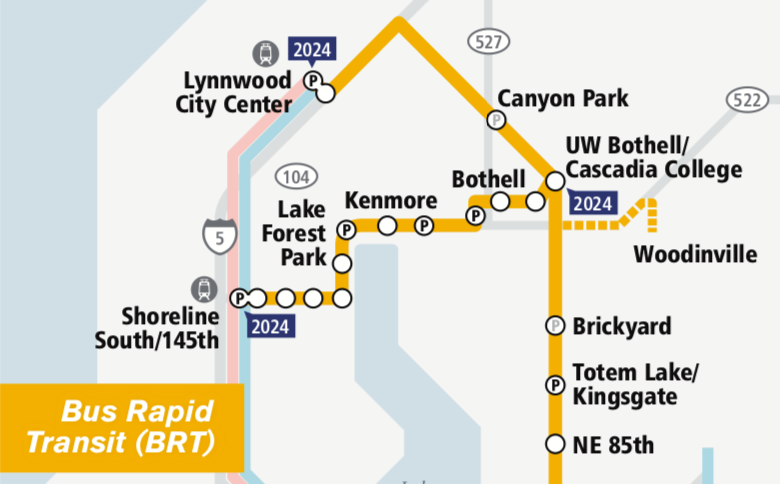

With the arrival of light rail planned for 2024, transportation planners must figure out a way to optimize N 145th St, an important east-west arterial, so that transit riders, pedestrians, and cyclists can move “safely and reliably along and across the corridor.” The result is Shoreline’s 145th Street Multimodal Corridor Project, which makes improvements along N 145th St from Aurora Avenue N to I-5. In addition to light rail, Sound Transit Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service is intended to begin operating on N 145th St between Shoreline and Bothell in 2024 (it also extends to Woodinville at lower frequencies).

While planned BRT on N 145th St will increase the amount of bus service and create transit signal priority and bus queue bypasses, it will not create business access and transit (BAT) lanes, which are reserved for transit use only apart from when vehicles use them for turn purposes. The absence of BAT on N 145th St is a sore spot for many transit advocates, especially since the Bothell Way (S-522) segment will have BAT lanes.

Nevertheless, the hope is that these light rail and BRT investments will reduce the traffic flow on I-5, easing congestion and allowing for larger volumes of traffic to move more efficiently through the area. Making accommodations for future population growth is particularly important because of Shoreline’s ambitious 145th Street station sub-area plan, which upzones nearly 70 surrounding blocks, effectively creating a new high-density neighborhood near the light rail station.

The above map displays the boundary lines for Shoreline’s 145th Street light rail station subarea plan. Station area 1, marked by indicated by bright green shading, allows for buildings as tall as 70 feet. Credit: City of Shoreline.

145th Plan Offers Significant Improvements, But Focus Remains on Moving Vehicle Traffic

There are many reasons why multimodal corridors are seen as an important urban planning tool. When done right, they can improve transportation and land use patterns in ways that reduce urban sprawl and greenhouse gas emissions. Because they rely on preexisting freeway infrastructure to carry the load, multimodal corridors also provide significant cost savings by maximizing right of way (ROW), thus minimizing land acquisition costs and enabling regional transit projects, like Sound Transit’s Link light rail, to proceed forward.

But the same freeway infrastructure that reduces cost also creates major design challenges.

“All things being equal, transit and freeways tend to flourish within their own, distinct land use and urban environments,” wrote the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in their book Reinventing the Urban Interstate: A New Paradigm for Multimodal Corridors. “With a few notable exceptions high capacity transit lines built in freeway corridors are generally designed with transit stations that optimize automobile access and circulation, often leaving transit, pedestrian, and bicycle access to stations as an afterthought.”

In other words, it’s hard to transition into a paradigm when construction takes place (literally) on top of the old.

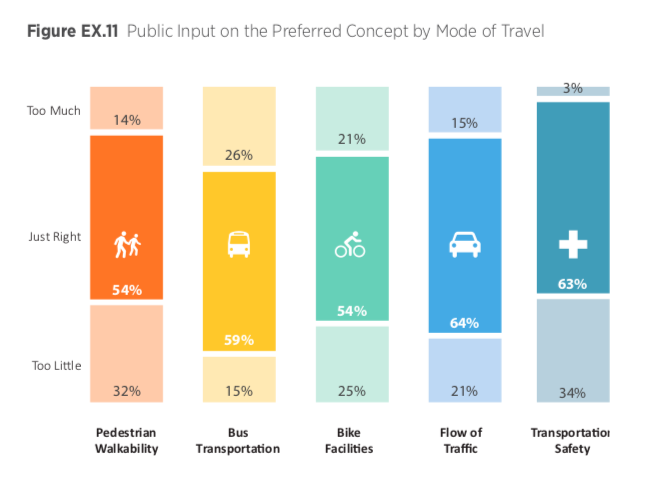

It would be inaccurate to state that transit, pedestrian, and bicycle access was treated as an afterthought in the N 145th St plan. However, a public survey conducted by Shoreline shows that 64% of those surveyed felt that the preferred concept got things “just right” for flow of traffic (ie. cars), while 54% felt that the pedestrian walkability component hit the mark. Over a third of those surveyed also expressed that the preferred concept offer “too little” in the way of pedestrian facilities.

The anticipated need for vehicle access to the light rail station is a major reason why movement of vehicle traffic through the corridor remains a top priority. The future light rail station will have parking for 500 vehicles, an amount that actually represents a decrease from existing stations like Tukwila (600 parking spaces) and Angle Lake (1160 parking spaces), but that could be because the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) conducted by the City of Shoreline found that there are currently about 1,950 on-street parking spaces available within the station subarea.

The number of spots could change as density increases in the area, particular because Shoreline has reduced parking minimums for new developments within a quarter mile of high capacity transit service.

The area’s most exciting new pedestrian and bike infrastructure will not be on 145th Street

Remaining true NASEM’s concept that different modes of transportation tend to flourish within their own urban environments, the most exciting new pedestrian and bike infrastructure investments are found off of N 145th St.

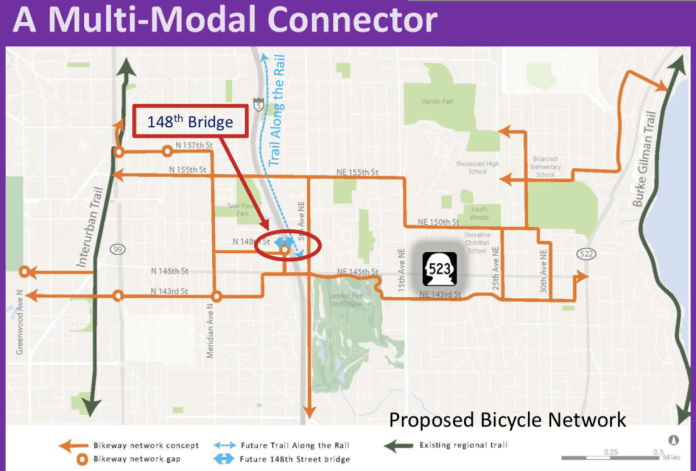

The most interesting of these is the N 148th Street non-motorized bridge, which allow for pedestrians and cyclists to cross over I-5 and connect with the 145th Street light rail station.

Because of the upzones in the station subarea, Shoreline foresees this bridge as connecting the future neighborhood that develop on both sides of the interstate.

The inclusion of the non-motorized bridge increases the half mile walk shed surrounding the future light rail station by 72 acres. It also plays an important role in connecting future bike facilities including two shared use trails, the Interurban Trail and planned Trail Along the Rail, and a neighborhood greenway network.

Looking at the corridor from a bigger vantage point, it’s important to point out that the 130th Street light rail station could also open in 2024. Sound Transit is currently undertaking preliminary engineering to see if it will be possible to speed up final design and construction of the 130th station. A decision should be made by the end of 2019.

130th Street has already been described by cyclists who travel through the area as offering safer conditions and better connections than 145th Street. It has also been classified as an urban station, meaning it will not have to offer parking and access to the 130th station will be prioritized for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users.

Opening the 130th and 145th Street light rail stations at the same time could offer a big win to light rail users. A coordinated opening would provide the opportunity to assess the area more holistically and take into consideration all of the opportunities and challenges that exist in this complicated corridor.

SDOT has created an online survey that people can use to share their feedback on its plans for the 130th and 145th Street stations. The survey can be accessed on the project website.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.