With Mandatory Housing Affordability in place in all urban villages, Seattleites are seeking additional answers for how to decrease displacement of low-income residents.

At the beginning of a recent “lunch and learn” session devoted to the topic of displacement at the City Council chamber, Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda joked that the meeting should have been titled “MHA: now what?”

The ink is barely dry on the legislation Mayor Jenny Durkan signed into law on authorizing citywide implementation of Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA), but already local political figures and community advocates are clamoring over how to address the problem of displacement in Seattle.

According to the UC Berkley’s Urban Displacement Project, residential displacement is “the process by which a household is forced to move from its residence — or is prevented from moving into a neighborhood that was previously accessible to them — because of conditions beyond their control.”

Commercial displacement, in which small, often minority-owned businesses are forced to relocate or close operations, usually occurs alongside residential displacement.

Largely attributed to gentrification, displacement is attracting nationwide attention these days, with many metro areas, including Seattle, puzzling over how to prevent it from further harming residents and communities. The question of how to create opportunities for people to return to their historical neighborhoods, such as in the case of African Americans displaced from the Central District, is also part of the discussion.

Back in February, Mayor Durkan signed an Executive Order 2019-02 which instructed the City to take action to “increase [housing] affordability and decrease residential displacement.”

Since then Councilmember Lisa Herbold has introduced her Displacement Mitigation legislation and the City Council at large passed a companion resolution to the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) bill calling for the City and its partners to “mitigate displacement and address challenges and opportunities raised by community members during the MHA public engagement process.”

Some MHA opponents, like SCALE, argued that the upzones passed with MHA legislation would result in older affordable housing being replaced by expensive new developments. It’s pretty clear that turnover predated MHA looking at the skyrocketing price of single family homes and rent hikes in naturally occurring affordable housing that was occurring — just without the affordability requirements. However, even some MHA supporters like Puget Sound Sage have voiced concerns that new development, particularly in areas defined as high opportunity/high displacement by the Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan, could have a net negative effect on lower income residents.

While displacement has been recognized as a problem in Seattle, Giulia Pascuito of Puget Sound Sage said it is “notoriously tricky to measure.” Thus the City is still largely in the dark as to how many residents are leaving their homes in Seattle or if the reasons why residents decide to leave qualify as displacement.

Increasing Tenant Protections and Relocation Compensation

In addition to legal actions, local politicians are trying show they are taking the problem of displacement seriously by holding community events.

On Saturday, March 16th, Councilmember Kshama Sawant hosted a special meeting of the City’s Human Services, Equitable Development, and Renter Rights Committee at True Hope Missionary Baptist Church in the Central District. Sawant referred to the meeting as a “Rally Against Displacement”, and the majority of the meeting time was devoted to a public hearing and a presentation by tenants of the Chateau Apartments, an older apartment building a few blocks away from where the event was held.

The proposed demolition of the Chateau Apartments and replacement with a new development attracted the attention of Councilmember Sawant’s office because it requires the displacement of fourteen Section 8-holding households. Additionally, some of the Chateau’s residents are elderly and have lived in the building for decades.

At the public hearing, the majority of speakers voiced support for the residents of the Chateau and concern about how escalating housing prices have fueled displacement. Additionally, Sawant received both praise and criticism for her work on the city council. Some speakers thanked her for her adversarial stance against corporate interests, while others said she had done little to help the community and that the housing crisis had accelerated under her watch.

Since the story of the Chateau Apartments hit the media a few weeks ago, the tenants have engaged in discussion with the building’s new owners, Cadence Development, which have promised to increase tenants’ relocation expenses.

In addition to the $3,850, low-income tenants receive for relocation assistance according to City law, Sawant staff member Ted Virdone confirmed that Cadence has agreed to pay $5,000 per household.

However, the tenants are seeking additional assurances from Cadence as well. In an open letter, tenants called for Cadence to assist with moving expenses for all households, ensure that each household is able to move to a comparably priced and sized apartment, and find housing within the Central District for residents who desire to stay in the neighborhood.

Those requests, as well as a call for Cadence increase the number of affordable apartments in the development, are not currently enforceable under City law, a point that was made repeatedly by Sawant, who said that the demands made by the residents of the Chateau Apartments where “very reasonable” and should serve as the template for a new set of tenant rights that guaranteed to all Seattle renters.

“The Chateau residents could have just accepted this money and moved on,” said Sawant, “but they want to fight for all Seattle renters.”

This is not the first time Sawant has called for the City to increase relocation expenses for displaced low-income renters. Last year, she proposed an ordinance that would have required landlords to pay three months’ rent to tenants who make less than 80% of the area median income. Her ordinance also would have made it the landlord’s responsibility to pay the full amount, whereas currently the cost is split equally between the City and landlord.

Sawant’s ordinance was unsuccessful and it remains to be seen if she will actually pursue a new ordinance based on the requests made by the Chateau Apartment residents. Furthermore, support for these measures from the rest of the city council is hardly assured. In fact, none of the other council members attended Sawant’s rally, a point that was referenced by some of the public hearing speakers.

While increasing tenant relocation compensation would not stop displacement, it might make it easier for tenants to remain in their neighborhoods; although with the current housing shortage, it seems unlikely that all displaced residents will be able to housing in their neighborhood of choice.

The Tenants Union of Washington State is circulating a petition of support for residents of the Chateau Apartments, and Seattle Office of Civil Rights, who leads the City’s Race and Social Justice Initiative, is holding a Community Speaks discussion in which community members can raise concerns regarding displacement and other topics of concern in the Central District on March 27th.

Housing Development and Anti-Displacement Strategies

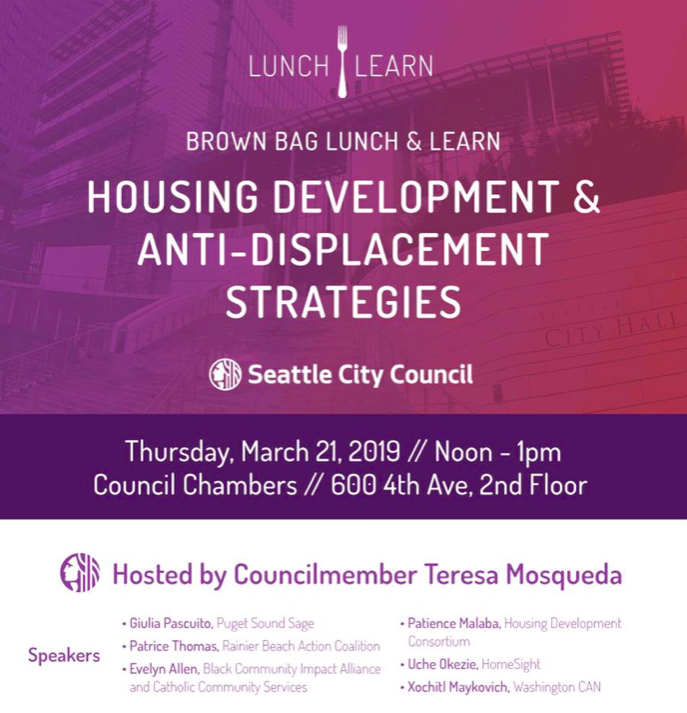

On March 21st, only one day after MHA legislation was signed into law by Mayor Jenny Durkan, Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda hosted a “lunch and learn” session in the Council Chamber devoted to the topic of displacement. Several short presentations were given local nonprofits and advocacy organizations, most of which highlighted the particular efforts being undertaken by their organizations to decrease displacement by creating new housing and job opportunities for lower-income Seattleites.

The organizations present were members of the Equitable Development Initiative (EDI), which according to the City’s website “has the dual purpose of mitigating displacement and increasing access to opportunity for Seattle’s marginalized communities who at risk of displacement as Seattle grows.”

A few of the speakers, including Patrice Thomas of the Rainier Beach Action Coalition, referenced the fact that the $5.5 million dollars distributed annually by the EDI falls far short of the funding needed.

Thomas commented that “a single affordable housing project can cost upward of $20 million.” Her organization is still raising money toward creating a Food Innovation Center near the Rainier Beach light rail station that would include affordable housing, a town square, and commercial space for small businesses. Rainier Beach residents first developed the idea of creating a Food Innovation District, a “renewed neighborhood plan with a vision at the center of which Food acted as a catalyst for neighborhood identity, cultural diversity and heritage, health, and job creation,” back in 2012.

However, while lack of funding for affordable housing development was a topic of concern, no specific strategies were shared during the session for how the City might raise additional funding.

MHA required contributions from developers should prove to be a new source of funding for projects like the Rainier Beach Food Innovation Center. Liberty Bank, which will have a ribbon cutting on Saturday, March 23rd, was financed in part by funds raised through the MHA program.

Finally, many advocacy organizations are calling for the City to move forward with passing a Community Resident Preference policy, which would give people who live in a neighborhood or have historically ties to a neighborhood preference in accessing affordable housing there. The City began exploring Community Resident Preference policy last summer, and Mayor Durkan called for the passage of such a policy in her recent Executive Order.

However, in other cities, like Portland, OR, the results of Community Resident Preference policies have been modest or mixed. In some instances, the policies have faced legal challenges under Fair Housing law. Thus, despite the mounting pressure from advocates, the City of Seattle will have to be very careful in how it moves forward with this policy.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.