The Puget Sound region is booming with new development, more residents and jobs, and demand for increasingly stretched public services, whether they be roads, transit, schools, or parks. Many jurisdictions require new development to pay impact fees to partially supplement capital funding to construct new facilities for these services.

Seattle, however, is one of the few cities that does not impose impact fees for transportation or schools. Seattle does have Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) and will expand that today, which is essentially an impact fee for affordable housing. Seattle also has a fee for sewer and electrical hookups, which are technically a form of impact fee but not in name. Under state law, impact fees can be used to pay for road improvements, school expansions, park and open space acquisition, and new firehouses.

Opinions on impact fees vary widely. Some boosters suggest that “new growth should pay for growth” — or put another way: that growth should pay for the new impacts to services that growth can create. Some hope that impact fees will curb new development. Detractors think they are designed to punish developers and that the costs are passed on in the form of higher housing prices. And some simply think that general taxation (e.g., property tax) is a fairer way to pay for growth.

However, the professional planning opinion locally, nationally, and globally sit squarely in favor of impact fees. Additionally, the economic research suggests that impact fees are a form of land value capture, causing lower land prices rather than higher housing costs. While there is evidence that impact fees can increase housing prices, research suggests that may actually be due to the additional services they provide. After all, well-funded schools often correlate to higher housing prices. Overall, planners and community members often see the policy is a fair way to fund the additional services needed due to growth.

Washington Statute on Impact Fees

In Washington state, impact fees are authorized under Chapter 82.02 RCW. The purpose of impact fees is to provide a financing tool for developing system improvements that will serve new development. The statute, however, is clear that impact fees must not be solely relied upon for financing new improvements. Instead, there must be a “balance between impact fees and other sources of public funds.” The statute is also clear that impact fees cannot be imposed arbitrarily or in a duplicative manner for existing impacts. They must be designed so that the impact fee cost is proportionate to the benefit that new growth and development will receive from improved and expanded public services.

There are also other clear limits to what impact fees can be imposed on and used for. Statute narrowly allows impacts fees for four categories of public facilities (owned or operated by a public agency):

- Public streets and roads;

- Publicly-owned parks, open space, and recreation facilities;

- School facilities; and

- Fire protection facilities.

Cities and counties that choose to impose impact fees must establish specific system improvements in their capital facility plans (CFP), an element of their comprehensive plan. In doing so, CFPs must clearly identify the following:

- Deficiencies present in public facilities serving existing developments;

- How deficiencies are planned to be eliminated within the next six years;

- Demand that new development will create for existing public facilities; and

- Needed public facility improvements to properly serve new development.

The golden rule to impact fees is that they must be fairly charged to new development. That means in developing a fee schedule, jurisdictions must look at use types and evaluate the kind of impacts that they create.

Residential uses, for instance, generally create a wider range of chargeable impacts than other categories of uses–such as schools, churches, and manufacturers–on parks and emergency services. Even individual categories of residential uses and occupancies may functionally operate differently, such as studio apartments versus five-bedroom single-family homes, and thereby present different demands.

Generally, impact fees are not collected until a building permit for a development is issued. In some cases, they can be further delayed. Statute also allows for impact fees to be exempted or reduced for low-income and affordable housing. Sound Transit also shares in exemption from all impact fees for buildings and structures built by or on behalf of the transit agency.

What Other Jurisdictions Do

Local jurisdictions impose wildly different impact fees based upon need and local conditions. Some jurisdictions impose impact fees for all eligible public facilities type; some only a select few. Some jurisdictions have interlocal agreements with other agencies, such as the Washington State Department of Transportation and nearby cities, to impose their impact fees as well when a development falls within their area of influence. And some jurisdictions have many different service areas for public facilities resulting in vary different impact fees by area. To illustrate this, three jurisdictions (Shoreline, Bothell, and Redmond) that impose impact fees are highlighted below.

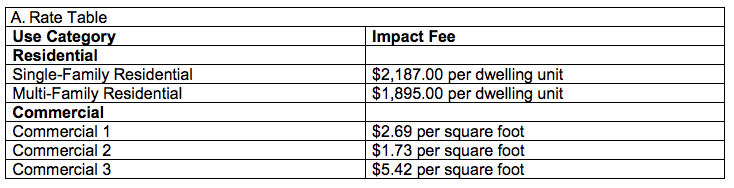

Shoreline imposes impact fees for transportation, parks, and fire services. While the jurisdiction uses a finer-grained approach to imposing impacts fees for transportation by use type, fire impact fees are consolidated to only five general categories for residential and commercial uses:

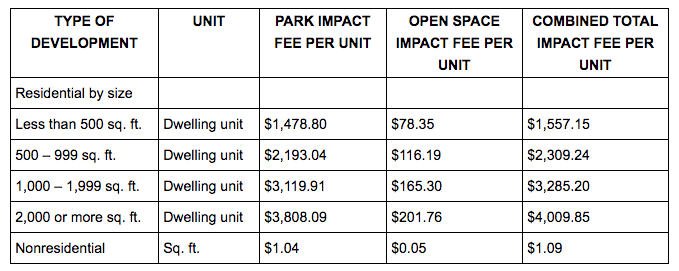

Bothell‘s park impact fee schedule is distiginguished in several ways:

- Residential uses are tied to the size of dwelling units, which is a shorthand way of suggesting how many people would live in a residence and their particular demands for parks and recreational facilities.

- The fee structure is separated into a standard park impact fee and an open space impact fee, the latter of which is focused on preserving open space assets instead of park and recreational facilities.

- Additionally, Bothell is somewhat unique in that it imposes park impact fees on nonresidential uses, which usually create their own park demands; most jurisdictions, however, have not acknowledged this linkage and therefore do not impose park impact fees on nonresidential uses.

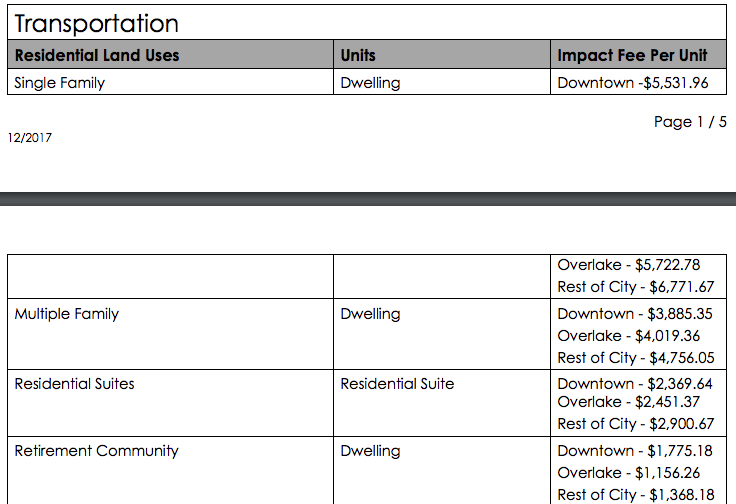

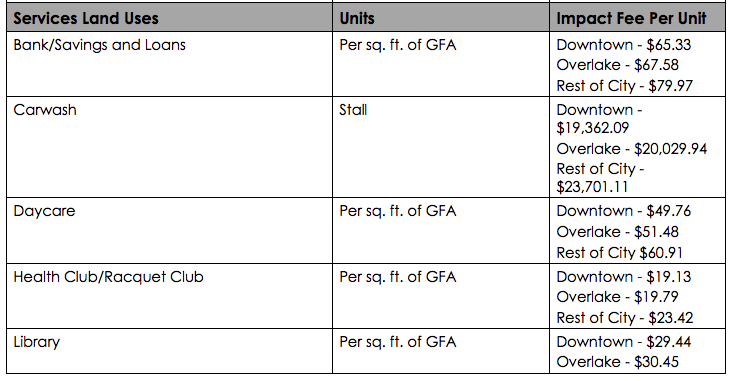

Redmond is perhaps one of the more unique and creative jurisdictions when it comes to impact fees. Not only does the city impose impact fees in all four allowed categories, they are highly tied to the type of use and geographic location in the city.

The Redmond approach resolves the unfortunate consequence experienced in other jurisdictions where impacts are more uniform with fewer categories valuing the impact of dissimilar uses as the same, which creates more apparent winners and losers. This is important because less fine-grained fee structures can unduly guide the decision that a developer may make in terms of bidding on a property for development and choosing higher cost-recovery uses (e.g., high-end retail over a laundromat).

These examples illustrate just some of the ways the impact fees can be structured. However they are imposed though, creating predictability for developers is vitality important. Setting the impact fee rate at the time of first application allows developers to deduct the cost earlier in the development process by factoring them into their pro formas–a pro forma is the building industry term for a set of financial calculations that spits out a projected financial return for a real estate proposal. This can be highly useful in discounting them at the property acquisition or contract purchase stage, for instance.

Many jurisdictions, however, choose to set applicable impact fees at the time of building permit issuance, in part because of the fact that larger developments can drag on for several years after submission of a land use application and may not reflect changes that have occurred under CFPs, which may alter impact fee assumptions and costs.

As Seattle evaluates the impact fee issue further, these considerations will be important to weigh in developing the city’s own structure.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.