Today Seattle City Council is voting on “citywide” implementation of Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA), a form of inclusionary zoning from which single family zones outside of designated Urban Villages are exempt. Looking back at the events that have led to this moment one thing is certain: nothing about the process leading to today’s vote has been easy.

And, unfortunately, if recent remarks by made by some of the the MHA louder critics are taken seriously, the City may find itself entangled in yet another legal battle in the near future. (More on that later)

I will admit that my first reaction to writing a post on the lead up to the big MHA vote was less than enthusiastic. After all, I did sit through five hours of the last public hearing, which even for a housing policy nerd like myself was a really long time and left me feeling like I had hit an MHA saturation point.

But, MHA actually has a very interesting history. These past five years have been full of contentious battles over a policy that was initially declared the “Grand Bargain” because of the note of compromise it was supposed to have struck between developers and affordable housing advocates.

Because of the wonder of the Internet, I can keep this post (somewhat) brief by including lots of links to many excellent articles that have been written on MHA, including many published by The Urbanist.

To begin with MHA’s history, we have to go way, way back–96 years to be precise–to when one of the main ingredients of Seattle’s affordable housing shortage was being baked into City code.

1923 – The Bartholomew Plan brings single-family zoning to Seattle

An excellent two-part series by Mike Eliason describes how a zoning ordinance created by Harland Bartholomew resulted in “sweeping downzones and initiated a slow strangulation of Seattle’s housing options.” While Bartholomew did not use the phrase “single-family zoning,” his work, which was predicated on keeping people of color out of affluent white communities, introduced Seattle to the concept of “first residence district zoning,” which functioned as a direct precursor to single-family zoning. Learn more about how the Bartholomew Plan by reading Eliason’s articles, This Is How You Slow Walk into a Housing Shortage and The Narrowing of a Neighborhood: Wallingford on Sightline Institute.

1980 to 1990 – A Decade of Legal Challenges to Seattle’s Housing Preservation Ordinance

In 1980 Seattle passed an ill-fated Housing Preservation Ordinance. The purpose of the ordinance was “to mitigate the loss of low income housing in the city caused by demolition for development and to reduce the hardships experienced by displaced tenants.” The law required that developers demolishing affordable housing pay a fee that was to be used to fund the construction and rehabilitation of low-income housing.

However, the ordinance was pretty much invalidated two years later by an amendment passed by the Washington State Legislature passed an amendment which made it illegal for any “county, city, town, or other municipal corporation shall impose any tax, fee, or charge, either direct or indirect, on the construction or reconstruction of residential buildings . . . or on the development, subdivision, classification, or reclassification of land.”

As a result a succession of lawsuits were filed against the ordinance, the last of which was resolved in 1990. Some MHA challengers, like Pacific Legal Foundation, have called on rulings related to the Housing Preservation Ordinance as part of the basis for their legal arguments.

2014 – Affordable Housing Linkage Fee

The fact that the construction boom in South Lake Union was leading to demolition of affordable housing and the construction luxury residential and commercial developments caught the attention of housing advocates, like Puget Sound Sage, who demanded that the City enact a linkage fee on new commercial development.

At this point the City was using Incentive Zoning as a means of raising funding for affordable housing; however, the requirements placed on developers by this process were acknowledged as woefully inadequate. In fact, from 2001-2013, the program only resulted in the creation of 714 affordable units.

Puget Sound Sage found an ally in Councilmember Mike O’Brien, who sponsored an Affordable Housing Linkage Fee policy that was approved by City Council in 2014. Developers could satisfy the requirements by either paying a per-square-foot fee, which was based on project’s location in the city, or avoid the fee by dedicating at least 3% – 5% of the units in their project to households making less than 80% AMI.

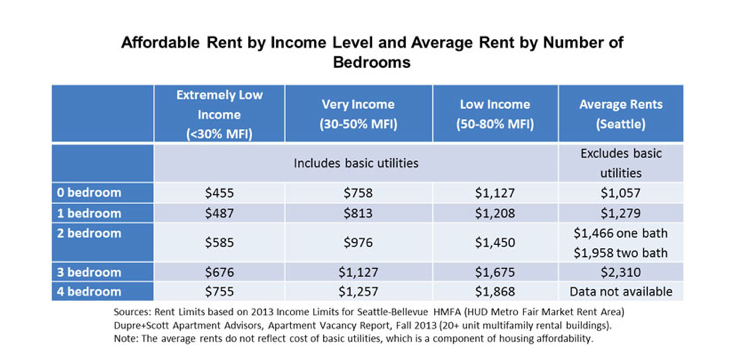

A review of some statistics and writing from this period show how quickly Seattle has changed. For example, in 2013 the average 1 bedroom apartment was still somewhat affordable to someone earning 50-80% of Area Median Income (AMI).

However, concerns were already mounting over what was rightly observed as an unhealthy growth in housing prices resulting from the regional housing shortage.

2015 – Developer lawsuits against linkage fee result in the creation of the HALA task force

Almost immediately after passage, the commercial linkage fee was threatened by lawsuits. Then Mayor Ed Murray convened a Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) task force to craft a legally defensible compromise. Over a nine month period the committee met and created the legislation that would become MHA. While some affordable housing supporters were disappointed by provisions that did not make it past draft phase, such as a move to remove slated zoning changes to single family neighborhoods, as a whole the legislation garnered support from proponents of density and affordable housing including The Urbanist’s editorial board.

2015-2017 – Community engagement and passage of initial MHA upzones

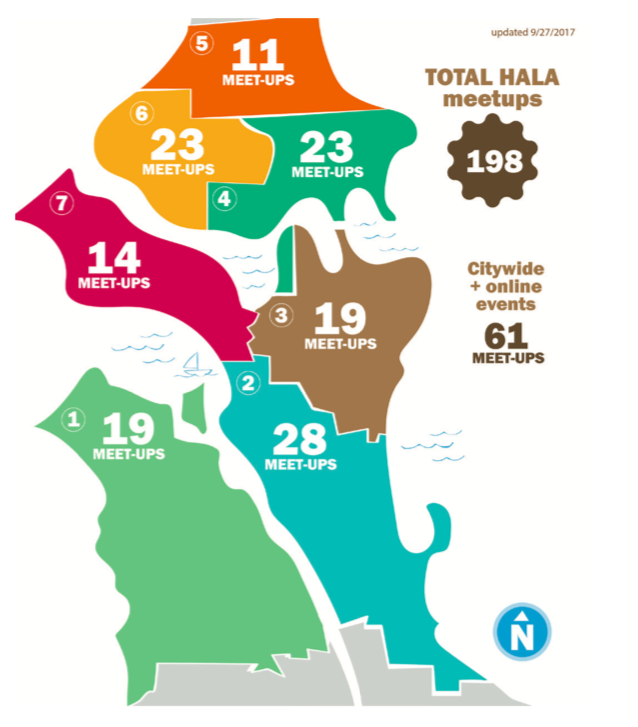

The next period was marked by widespread community engagement efforts led by the City.

During this period the City Council voted unanimously to establish MHA requirements and rezones in the following communities: University District, Downtown, South Lake Union, Chinatown-International District, along 23rd Ave in the Central Area, and Uptown.

2017 – SCALE enters its first appeal

However, despite the community outreach conducted by the City, MHA became to gain its fair share of critics including the Seattle Coalition for Affordability, Livability and Equality (SCALE) which claimed that implementation of MHA trampled over individual neighborhood plans.

Their appeal, filed in November of 2017, took on nearly every aspect of the plan’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and even though early rulings favored the City, supporters had to wait a full year for the case to be resolved.

2018 – Judge rules in favor of MHA

Citing the fact that the upzones that had already put into place as a result of MHA had not resulted negative impacts to the surrounding communities, the presiding judge ruled in favor of citywide implementation of MHA in November of 2018. Some small adjustments were required of the plan, notably in the area of historic preservation, but as a whole MHA was allowed to move forward.

2019 – Will MHA finally become a reality?

After debating a slew of amendments, the Special Committee on MHA unanimously advanced the policy to an all council vote.

It is fully expected that the Seattle City Council will vote in favor of citywide MHA implementation. However, critics are already planning new lawsuits against the legislation.

- Roger Valdez – a developer lobbyist who is vocally opposed to MHA because he believes it will curb development and increase housing prices in the long run said in a debate with Councilmember Rob Johnson on KUOW’s The Record that he is planning to sue the City over MHA.

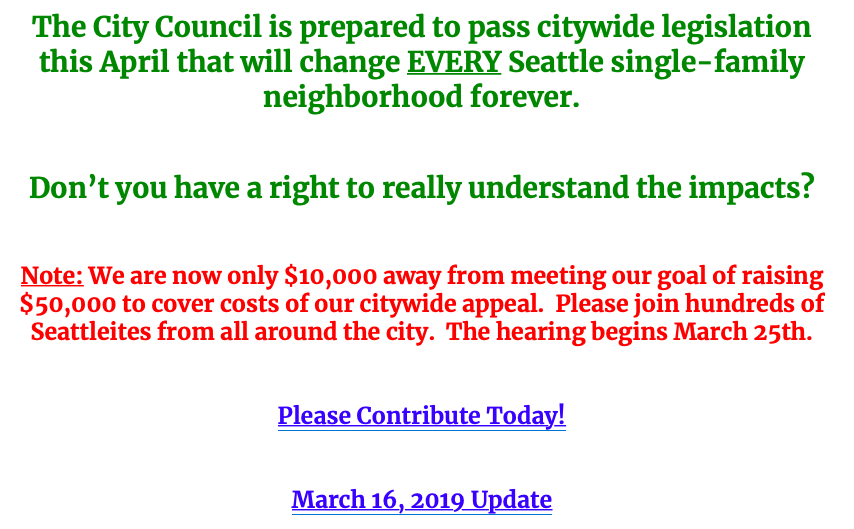

- SCALE announced in a recent press release that they will be meeting with media prior to the final MHA vote, and that they are “considering whether to file suit under Growth Management Act (GMA) to overturn MHA.” They are also actively fundraising for Seattle City Council candidates that oppose MHA.

- Queen Anne Community Council (see below) is actively fundraising for a citywide appeal of the City’s Accessory Dwelling Unit reform. Kaplan has also been a vocal critic of MHA and published an editorial criticizing MHA in the Seattle Times the day before the final vote. It seems likely that QACC will continue to oppose upzones and other zoning changes in the future.

So even after council approves MHA today, proponents will still need to hang tight as the lawsuits and appeals come in.

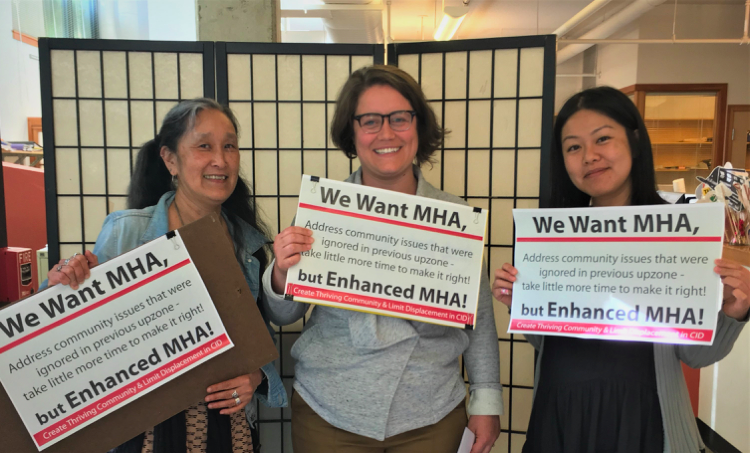

Finally, displacement of low-income tenants has arisen as a major topic of concern. Puget Sound Sage recently stated that “MHA was not the answer we’ve been hoping for” and have publicly called for anti-displacement measures to be passed alongside MHA.

After the final MHA vote, the council will still need to consider the Displacement Mitigation legislation put forth by Councilmember Lisa Herbold. Although aimed at preserving affordable housing, some councilmembers have expressed concerns that it would negatively impact housing capacity and affordability in the long run. As a result, it is entirely possible that additional anti-displacement or tenant rights oriented policies will enter into discussion in the near future.

Note: the article was revised to reflect the fact that the Queen Anne Community Council is fundrising to appeal against citywide ADU reform, not citywide MHA implementation. QACC president Marty Kaplan continues to be a vocal critic of MHA.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.