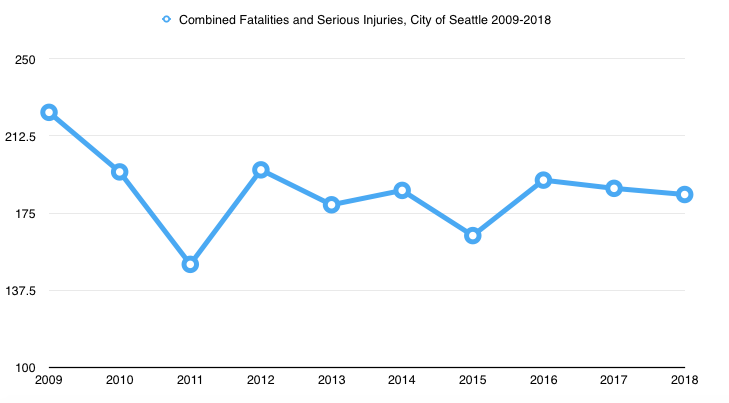

Preliminary data from the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) shows the total number of serious injuries and fatalities on Seattle’s streets was virtually unchanged between 2018 and 2017, showing another year of stagnation toward our citywide goal of completely eliminating those types of collision results by 2030.

This data comes just as the nationwide projection for pedestrian-involved injuries in 2018 indicates that last year saw the largest number of deaths of people walking on America’s streets since the George H.W. Bush administration. People walking continue to be a large share of those injured in Seattle.

SDOT’s Vision Zero team will present its update to the city council’s transportation and sustainability committee this week with a silver lining taking center stage: only 14 people lost their lives on Seattle’s streets in 2018, the lowest number since 2011. To be sure, these numbers are preliminary and may change, but fewer people losing their lives on our streets is welcome news.

However, with the inclusion of serious injuries in the figures, there was only a reduction of 1.5% between 2017 and 2018–170 people were seriously injured while using our streets last year, up from 168.

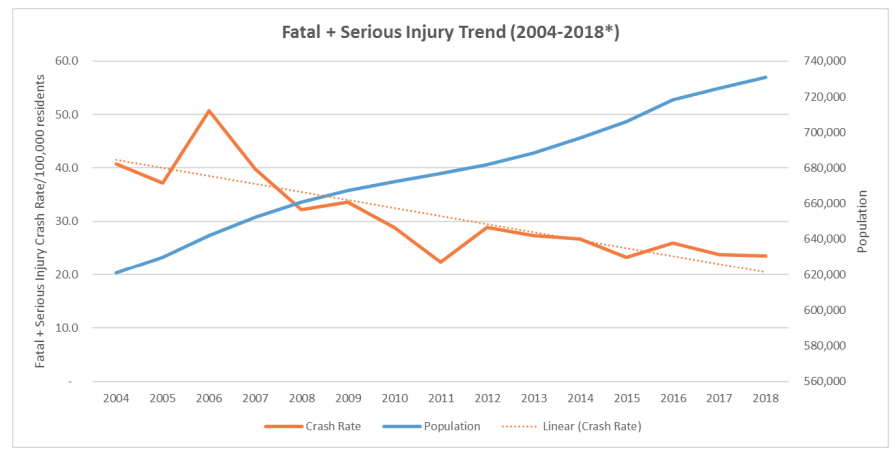

In trying to identify longer term trends outside the year-to-year fluctuations, the numbers reveal that using Seattle’s streets during the past five years (2014-2018) was essentially as dangerous as the previous five years (2009-2013), with a reduction in total serious injuries and fatalities of only 3%. By contrast, 2009-2013 saw a 25% reduction in collisions and serious injuries compared to the five years before that, 2004-2008.

It’s true that Seattle’s population has grown as the city has treaded water on improving safety in the past few years. But again, Seattle’s population was growing in 2009 through 2013 when the city still saw double digit gains in safety. Tuesday’s presentation includes a chart that adjusts the numbers per 100,000 residents, making the trend line slope downward. But zero cannot be population adjusted, and the past ten years still show clear stagnation.

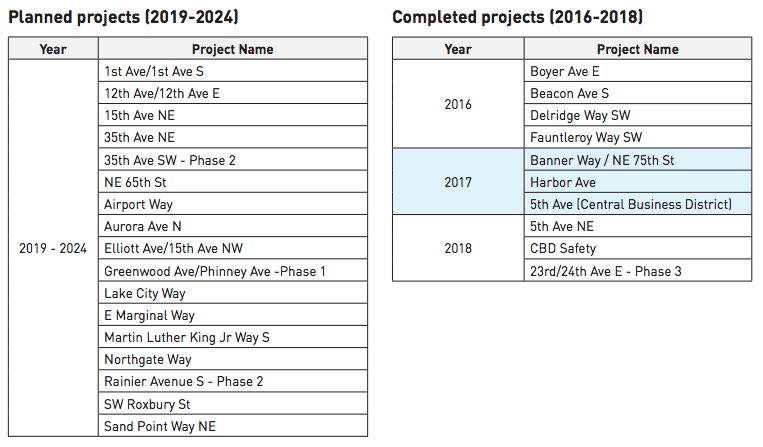

The Move Seattle levy committed resources to reducing traffic injuries with a large number of its subprograms, but the most targeted is the Vision Zero corridor program. Contrasted with the bicycle master plan, or with the new sidewalk program–just two examples of programs that are likely not going to meet the original levy commitments due to a funding shortfall–the Vision Zero corridor program is considered on-track to exceed its original goal of 12-15 corridors over the life of the 9-year levy. The workplan shows plans for 27 separate corridor safety projects by 2024, with 10 of those already completed.

These corridors, which have an average project cost of a little more than $1 million, can vary in scope and impact, and the design of the proposed changes can often fall victim to considerations that are not in line with the goals of maximizing safety impacts.

Looking at the list of completed projects in the work plan, many of them are problematic in a list of projects intended to have a large impact on public safety. Fauntleroy Way SW improvements are currently getting scaled back after that project was put on hold pending a Sound Transit alignment decision. Improvements to 24th Avenue E were so minimal the inclusion of this project at all seems to call the entire list into question. Safety improvements to Beacon Ave S amounted to spot improvements at a single intersection. And improvements in central Downtown on 4th and 5th Avenues were mainly completed for the benefit of moving cars (and therefore buses) during the period of maximum constraint, not for the safety of pedestrians downtown.

It’s also worth noting that the workplan for the remainder of the levy only includes one project that touches Downtown, where a hugely oversized portion of injuries and fatalities happen due to the confluence of different modes.

So far in 2019, Seattle has seen people lose their lives on corridors that are on this list: Rainier Avenue, Lake City Way, 4th Avenue. The cost of falling short on making improvements here is measured in impact to human lives. We will be able to call the vision zero corridor problem a success when lives stop being devastated by these streets, not when we have checked a box showing how many we’ve done.

It’s time to take off the rose-colored glasses and start to get to work making significant progress slowing down vehicles, separating vulnerable users from dangerous situations, and enforcing existing traffic laws intended to keep users safe.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.