The final public hearing on citywide implementation of Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) was long and contentious. Hundreds of speakers waited for hours to present their two-minute testimony on legislation that would increase upzones in exchange for affordable housing creation–6,000 affordable homes are projected the first decade alone.

At the public hearing Thursday, some speakers’ testimonies were heartfelt, others belligerent. Despite a few memorable exceptions, such as a late night spoken word performance about “density Bolsheviks,” the dialogue largely grew more civil as the evening progressed.

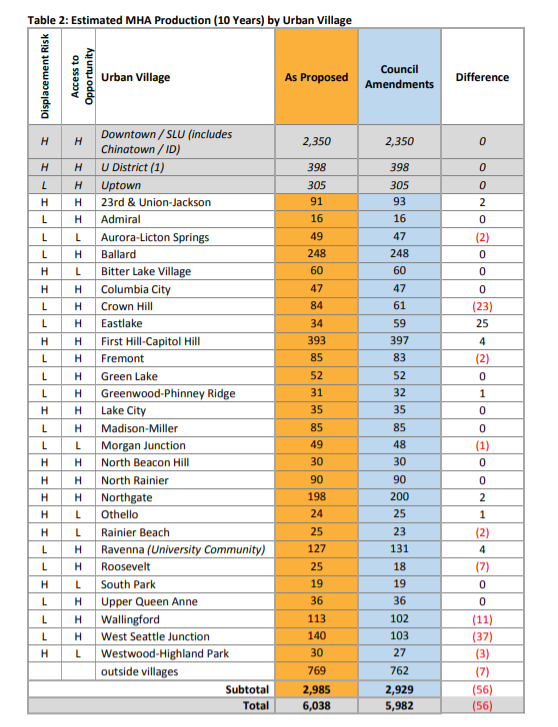

A lot of people came out to speak in favor of specific amendments, like Councilmember Mike O’Brien’s amendment proposing zoning changes in the Crown Hill urban village. The Crown Hill testifiers said they wanted MHA implemented citywide and felt that O’Brien’s proposal, which requests taller upzones on arterials and lower zoning for surrounding streets, would result in a more vibrant business district in Crown Hill without reducing the amount of new housing that would be created. Unfortunately, a Central Staff analysis found the opposite; the Crown Hill amendments would take a toll on affordable housing production to the tune of 23 rent-restricted MHA units and more than 300 homes overall in the next decade, according to projections.

However, inflammatory rhetoric from the anti-MHA contingent brought a level of bitterness to the debate that was hard to shake off. Statements like, “I ain’t no HALA crack girl” are simply unforgettable. I had to hear it twice before I could believe what I heard.

From the beginning, it was clear that the MHA public hearing was about far more than a piece of housing legislation. Two very different visions of Seattle were held in contention, with generational fault lines pitting older and wealthier homeowners against younger workers facing housing insecurity and skyrocketing rents. I felt this divide distinctly as I slid into my seat next to a woman a couple of decades older than me, who despite saying she was there to “observe and learn” held an “MHA = Gentrification” sign and clapped loudly at all criticisms hurled at the “new” Seattle.

The generational divide was captured clearly by Calvin Jones of Tech 4 Housing:

Zoning is a generational issue. When 70% of the city is zoned for the most expensive type of housing and the least environmentally friendly type of housing that creates huge problems for young people.

Not only will we not be able to afford… to buy homes in the city, but it’s contributing to emissions that will drive climate change that my generation will mainly bare the burden of.

In order to deal with this we have to pass MHA as quickly as possible and then we have to take a very hard look at the city’s single family zoning.

Calvin Jones, MHA Public Hearing, 2/21/19

Jones’ climate concerns were echoed by the Sierra Club, Seattle 350, Architects for Affordable Housing, and others.

There were a some exceptions to the generational divide. One of the night’s most memorable statements came from Randy Riedl who said he found the idea of the idea of 30-40 people one day living on his West Seattle lot to be “delightful.”

Big tech backlash

Controversy over how the tech industry’s growth has impacted the city was a recurrent theme throughout the public hearing. The term “tech trash” was repeated as both a slur and rallying cry, laying bare the feeling of generational resentment bubbling beneath the proceedings’ surface.

In a statement that opened with references to tech bros, venture capitalists, and blocks and blocks of ugly boxes, “the true reflection of the new Seattle,” Lisa Kuhn first tossed the term “tech trash” into the debate:

“We’re lucky. My husband and I had spectacular housing karma and part of the way through this it became clear to us… that not only did we need to leave, but that we had some place to run to.

All I had to do was say we were being run out of Seattle and they welcomed us with open arms…

I worry because let’s face it, when the tech trash gets bored with strip-mining Seattle, where are they going to try to follow us? It may be too late for Seattle but there are places out there that can be saved, where everyone has value. So it’s time to run, if you possibly can. It’s time to leave. Go out, find those places and protect them, and good luck.”

Lisa Kuhn, MHA Public Hearing, 2/22/19

“That’s so sad,” murmured the woman seated beside me as Lisa Kuhn left the podium, a reaction that surprised me. While Kuhn’s anger and sadness felt very real, I struggled to sympathize for her. She was simply too vitriolic and failed to acknowledge how the growth of the tech industry had contributed to her “spectacular housing karma”–not to mention her White privilege had given her the chance to seize this spectacular investment opportunity and then appropriate Hindu spirituality to rebrand her capitalist gains. Ah shucks must be my Karma!

Kuhn also failed to explain exactly why she had felt been driven out of Seattle. Her complaints about congestion, lack of available parking, and “ugly” new architecture, all widely shared by the anti-MHA crowd, do result in a quality of life adjustment, but not displacement.

Simply put, if you have freely chosen to leave, you have not been displaced.

Instead of Kuhn, I found myself rooting for people like Nick Woods, a self-described tech worker who earns $19 and moved to Seattle to “live more sustainably while improving [his] career prospects,” or Tom Allen, who shared several emotional stories of friends who had been displaced. “The status quo is causing displacement,” Allen said. “Go as big as you can.”

But, I am from a different generation and I have watched a lot of friends leave, never by choice and rarely with a better option to run to. I worry that even my younger sister, a nurse practitioner by trade, might eventually feel overwhelmed by the lack of affordable housing choices and leave too.

Housing karma is a generational issue

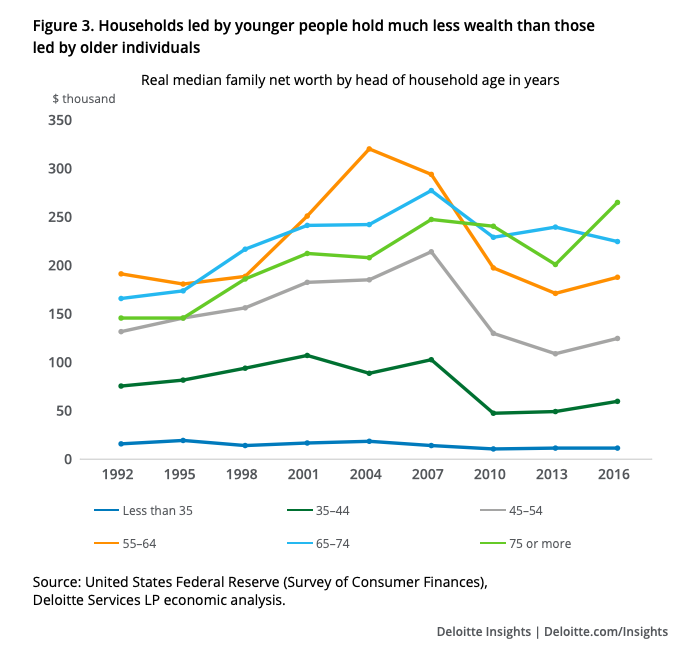

“Spectacular housing karma” is a major life changer in the US. We live in an era when the generational wealth divide might be the steepest it ever has been. Incomes for households headed those 35 and younger have been declining in comparison to other age groups for decades. According to analysis by Deloitte Insights, in 1992, the ratio of real median family net worth among households headed by those 75 or more years old to that of households headed by those under 35 years old was 9.4. By 2016, that ratio had increased to 24.1.

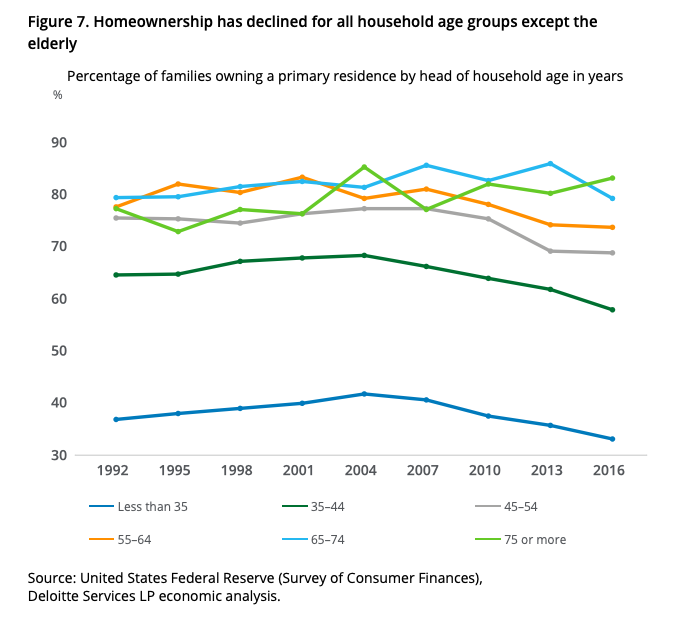

Additionally, while homeownership rates have been declining among all age groups except those 75 and older, it is the 35 and younger group who has experienced the stiffest declines.

Even Seattle’s well paid tech and other “knowledge economy” workers, have not been immune to that trend. According to a 2018 Politico article, only 29 percent of Millennials in Seattle are homeowners, which is well below the national average of 34 percent.

Thus, despite the fact that Seattle’s Millennials earn more, on average, than in any other US city, over fifty percent fear they’ll be forced to move because of high housing costs.

The current housing crisis cannot be blamed on younger workers. Instead it is the result of regional- and national- housing affordability woes. In a recent interview with Geekwire, Downtown Seattle Association CEO John Scholes stated that the tech sector had been “unfairly blamed for the situation we face today.” Of course tech executives could make it easier on their employees and their neighbors if they didn’t block new funding for affordable housing production.

A review of the numbers reveals a basic truth. Housing growth in Seattle has simply not come close to matching population growth. The blame needs to fall on the lack of housing diversity and options. In fact, while the city has added over a hundred thousand new residents over the last decade, some Seattle single-family home dominated neighborhoods, included many represented by SCALE, the organization that appealed MHA’s Environmental Impact Statement, have actually lost population.

Jacinta Fitzgerald, who described herself not only as “tech trash but also an immigrant,” stated how lucky she felt to be an owner of one of the “ugly box” townhouses critics decried throughout the night. Ownership of her townhouse has given Fitzgerald a level of housing security as many of her peers have been priced out.

“People like me will keep coming here,” said Fitzgerald, unafraid to present herself as a poster child for some of the NIMBY’s worst nightmares. “Pass MHA and get started on the next step.”

Fear of change

Among the anti-MHA crowd, nostalgia for the past was as omnipresent as anger toward developers and techies. Fear of change versus acceptance of change was another major dividing line.

Dylan Kate said, in his testimony against CM Herbold’s proposed amendments, “What makes my neighborhood great is not that it doesn’t change, but that it is always changing.”

However, many on the anti-MHA side disagreed.

Speakers lamented the “lost” Seattle, an affordable cultural capitol where people were able to rent office space for their small businesses on the Pike-Pine corridor for $100 per month and musicians were able to purchase single-family homes in Wallingford in which their bands could play their music as loud as they wanted to.

Rather than helping restore affordability of the past, for those who expressed this nostalgia, MHA was presented as a new accelerator of gentrification.

Greg Hill spoke of the “charlatans promoting MHA,” questioning why MHA supporters were intent on increasing housing prices and “driving families out of Seattle.”

A short appearance by a Vulcan Real Estate spokesman, who gave a short statement in favor of MHA, only added fuel to the fire, despite that fact that nonprofit housing developers like Bellwether and Plymouth housing also spoke in favor of the legislation.

Interestingly, while there was a lot of mention of the importance of preserving affordable housing and support for Councilmember Lisa Herbold’s anti-displacement legislation, none of the speakers who spoke against MHA self-identified as a renter who felt endangered by potential displacement or who had been displaced by upzones.

Instead speaker after speaker self-identified as homeowners, almost entirely of single-family homes. Generationally pointed comments were made suggesting that the perceived “young” people supporting MHA now might regret it later when they wish to own their own single-family properties.

Yet no plan was presented by dissenters for how to restore past affordability levels. Neither were no any ideas shared for how today’s younger workers might leverage their way into the “spectacular housing karma” enjoyed by previous generations.

Housing and magical thinking

Like Dorthy in the Wizard of Oz, statements from anti-MHA crowd implied that that if they shut their eyes, held tight to their houses, and waited long enough, the hundred thousand plus people who have moved to Seattle might magically vanish.

But the people who oppose residential growth in Seattle have no ruby slippers or good witch Glinda. And it can be argued that magical thinking has played a significant role in getting us into this mess in the first place. After all, isn’t it magical thinking to believe that a city can experience such a high rate of population growth and not significantly change in its demographics and built environment?

After taking my seat in the council chamber, the woman next to me chatted on for a while about the origins of MHA. When I made reference to the fact that Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) had been initiated four years ago, she was quick to correct me.

“Oh no,” she insisted, “this has been going on for at least twenty years. Maybe longer.” She went on how to describe how she had been worried about the effect upzones would have on Seattle ever since she brought her affordable single-family home in south Beacon Hill in the early nineties.

The HALA “grand bargain,” which includes MHA, was passed in 2014, but the cultural battles over density and up ones go back much further. That got me thinking. What if twenty years ago, right at cusp of the new millennium, different housing zoning decisions had been made? What if the question had been, not if Seattle should be built denser, but how to make the new density better? What is we had passed the inclusionary zoning that MHA is finally introducing before the building boom?

If we had allowing zoning and housing production to keep up with population growth, then the testifiers–young, old, and all the ages between–could have instead simply spent the evening comfortably at home, in whatever type of home met their needs, budget, and lifestyle.

A few days ago, I attended a History Cafe event at MOHAI on the theme of “Seattle’s That Might Have Been.” A Seattle in which housing growth held pace with population growth over past decades was never presented as one of the alternate versions of the present, but it absolutely should have been.

The next city council select committee meeting on MHA will be held on today February 25th, and the final all council vote is schedule for March 18th.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.