On Tuesday, the Seattle City Council was briefed on the Center City Connector project, which was recently backed by Mayor Jenny Durkan. The project was put on hold after modest project cost increases and dispute over future operating costs with King County Metro came to light in early 2018.

Over the summer, a consultant hired to evaluate the cost and benefits for the project affirmed that costs did go up but that projected ridership could also rise, making the financial issue somewhat of a wash. Then in January, Mayor Durkan finally released an updated engineering report that suggested additional design changes could be useful, though some were not an operational necessity.

During the meeting, Councilmember Lisa Herbold asked if the city would pursue cost recovery from the vendor of the new CAF Urbos streetcars that city would be purchasing. Her line of questioning really got at the issue that the streetcars have created some system engineering challenges that may not have been fully vetted by the vendor in developing their proposal, leaving the city otherwise on the hook to pay more to resolve the challenges. “It’s something that we’ll work with the [vendor] to negotiate as we move forward with the project,” said Karen Melanson, Deputy Director of Policy, Programs, and Finance for the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT).

When Mayor Durkan declared her support for the project, additional cost increases, above those identified by consultant KPMG in the summer, were disclosed: $285.8 million versus the earlier $252.2 million. “The current city estimate builds on the KPMG work and adds in the additional engineering analysis as well as escalation for construction with revenue estimated to be in 2026,” Melanson said.

The KPMG analysis differed in that it neither included additional engineering analysis costs nor went beyond 2022, when construction was assumed to wrap up. City Budget Director, Ben Noble, said that at the time of the KPMG report the city did not know that 2026 would be the actual year of completion due to the engineering issues. Most of the cost increase therefore is escalation due to added time and inflation, not because the KPMG estimate was inherently wrong.

Noble also confirmed, in response to a question from Councilmember Johnson, that most of the $6.2 million cost increases for Seattle Public Utilities and Seattle City Light capital projects were cost escalations.

In terms of the streetcar cost increases, the January estimate was $27.4 million more. The lion’s share of the cost increases were escalation costs, SDOT said. The exceptions were design ($1.5 million), administration ($1.8 million), and integration ($14.1 million) costs. Councilmember Johnson speculated that these might be the costs that could be partially if not fully passed back to the streetcar vendor.

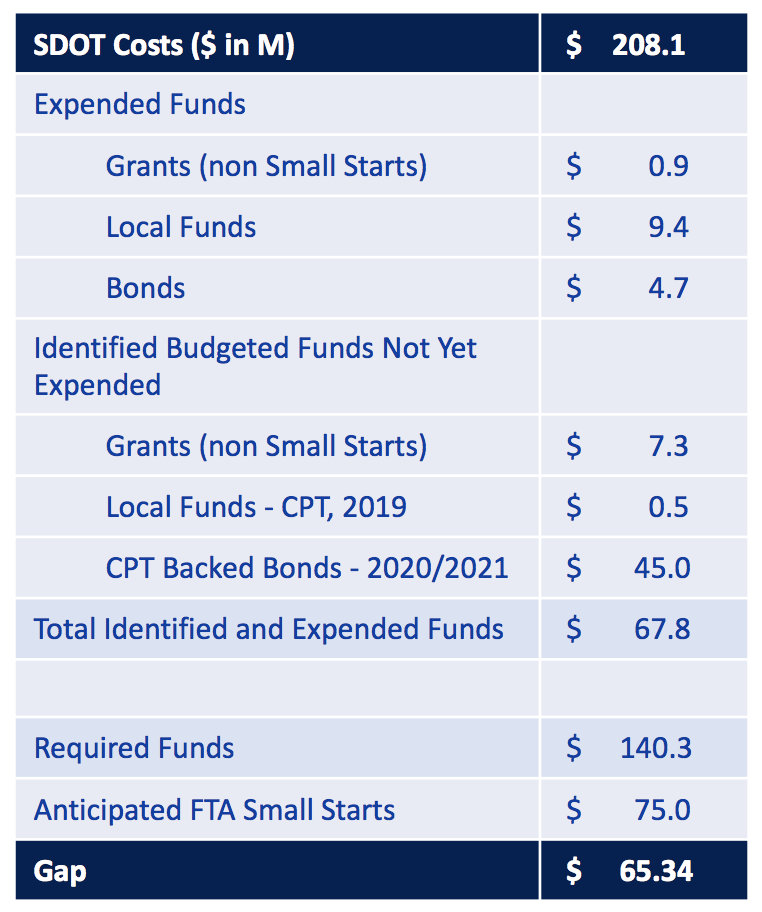

Excluding the capital expenditures for utilities work, most funding that has been set aside for the Center City Connector streetcar project has not been spent, even though most of the funding has been identified:

SDOT expected to receive a $7.3 million Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality grant from the Puget Sound Regional Council to purchase the streetcar vehicles and has $500,000 from the Commercial Parking Tax approved for continued work to plan and coordinate the project this year. Another $45 million will come from Commercial Parking Tax-backed bonds in 2020 and 2021. Assuming that the other $65.34 million in unidentified funding sources are secured, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) should come through with a $75 million grant for the project ($50 million is guaranteed and another $25 million is expected after additional review).

“One of the things that we know and we don’t think has changed is the project…again for now a higher cost, in some sense a relatively smaller cost compared to many transit projects by connecting two existing systems that are sort of struggling in operations and isolation in drawing that connection,” Noble said. “You get a very significant ridership and a very significant benefit. Bottomline, the FTA will do their own analysis, but we expect the project will compete well on the Small Starts criteria.”

The Value of Redundancy

Councilmember Herbold asked if the streetcar corridor (partially) overlapping with other rail lines might affect the equation. Melanson responded that the FTA will look at the ridership projections and models of the streetcar project itself, which demonstrates on its accord the project value.

Councilmember Mike O’Brien also pointed out that partial overlap could have positive impacts, not negative ones to system use, similar to increasing transit frequencies and building upon networks in general, inducing more ridership overall. “With a network effect, now there’s potentially tens of thousands of riders every day the could get off at a certain location with a connection to the streetcar, too,” he said. “But you would hope that one would at least attempt to model that, whether it’s a positive or negative.”

Eric Tweit, Project Manager for SDOT, said the ridership numbers were derived from modeling conducted in 2014 using the FTA’s “STOPS Model“. He said that the model accounted for “conditions expected to be in the transit system as a whole by 2035.” That included known light rail extensions at that time. The ridership numbers were then updated this past fall “with a recalibrated version of the STOPS Model,” accounting for things like recent ridership on the South Lake Union streetcar line, which has seen a 2% ridership decline. Ultimately, that modeling scenario determined that ridership would be in line with what KPMG projected last summer.

Councilmember O’Brien made another observation about how alternative options can be a good thing for a transit system and riders, offering “multiple different connections” and choices. “Maybe on some days you decide that [you] want to take the two escalator rides downstairs to get on something and then reverse it at the other end,” he said. “Or [you’ll] just hop on something on the street, it might be slower that way but not a longer walk. But we do know that when people have lot of different options, that’s a benefit.”

“One of the things we asked KPMG to do was look at the ridership model, and they did a little bit of verification as well. I think that–I’m not a transit planner, I’m not guaranteeing you 5.7 million,” Noble said. “But the very real sense is that there is a significant opportunity here.” One example that he highlighted as an opportunity was much more direct connectivity to the West Seattle water taxi, which saw ridership boom to three times the normal during the Seattle Squeeze. He also said that there are benefits for better serving the western portion of Downtown and having dedicated transit lanes.

Councilmember Johnson was quick to point out that while the South Lake Union line has seen a small ridership decrease, the city has invested heavily in adding and extending service into the area that competes with the line, such as the RapidRide C and D Lines. He explained in the latter case, people would have been transferring to the streetcar likely before, which demonstrates how persistent ridership on the streetcar has actually been.

“Redundancy in the transportation system is a good thing. I think I just want to remind people of that,” Councilmember Johnson said. “We wouldn’t say no to the buses on Third Avenue because we’ve got buses in the tunnel. We want buses in the tunnel, we want buses on Third, we want transit pathways all throughout the system….The overwhelming majority of people come into Downtown every day on something like a bus. So the more we can have those redundancies, the better off our system moves.”

Operating costs

Calvin Chow, a legislative analyst, made a quick point about the network effect and financial consequences of owning only a portion of a network. “The more network we have, the more we assume transfers, and the more that actually dilutes some of the revenue pool,” Chow said. “So it has a different impact potentially on the finances on the system, separate from the ridership.” His point was that the long-term operating costs may bear out differently from just ridership on the system, even if that ridership count is considered good.

Looking to the year of first operations once the Center City Connector bridges the two streetcar lines, subsidies required from the city could reach $18.09 million despite robust ridership gains. Current budgeted subsidies from the city are approximately $4 million. The difference in cost is partially due to more overall operations (more total service and vehicles), but a large part of the $14 million cost increase is because King County Metro and Sound Transit plan to withdraw their subsidies in the next few years.

Sound Transit provides the largest transit agency subsidy of $5 million per year because they funded construction of the First Hill Streetcar line after failing to deliver a light rail station to First Hill as part of the University Link light rail extension. It stands to reason that Sound Transit should continue to pay out annual subsidies in perpetuity for constructing the line just like they would for any light rail line they built, but that does not appear to be the transit agency’s position.

Noble said that the city is still negotiating with both transit agencies on the issue, as there are areas of leverage. However, with or without the Center City Connector, the city would still be on the hook for increased operational subsidy payments if the city ultimately fails to prevail on the issue. For now, the city has sufficient funding sources identified through 2024 to cover operational subsidies, but so far has not budgeted for after that, making the “who pays?” issue an important one in the years ahead.

Double standard for subsidizing streetcars

“I think about this slightly differently than the word ‘subsidy.’ For me, this is about an investment in infrastructure that our citizens support,” Councilmember Johnson said. “When we get presentations about the ways we spend the Seattle Transportation Benefit District money and the bus service we buy, we don’t call that a ‘subsidy’ of King County Metro bus service. We call that an investment in additional ridership and additional options for our riders.” Councilmember Johnson also pointed out the city does not set minimum farebox recovery goals for the service that the city buys. The King County Council has set a 25% farebox recovery ratio target, which the streetcar easily meets.

Joining the conversation on subsidies, Councilmember O’Brien noted that paying for roads is not often talked about in terms of subsidies and farebox recovery in normal discourse, even though their costs are heavily covered through a variety of public subsidies. Road users rarely pay for the actual cost of roads through user fees, like tolls, when using them.

“When we first looked at just tying the loop the Center City streetcar, nobody was talking about the Seattle Center Arena. It wasn’t even a twinkle in anyone’s eye at that point,” Councilmember Sally Bagshaw said. “We know that it’s going to be 15 to 17 years before we actually get light rail from Downtown to Seattle Center. I’m really interested in how we’re going to move people to and from in those 15 years.” She added that community members in Belltown are interested in a First Avenue connection either as streetcar or buses in dedicated lanes.

The corridor that Councilmember Bagshaw thought should be served stretches from Mercer Street to Lander Street, which mirrors what the Seattle Streetcar Coalition has advocated for and similar to what transit advocate Charles Bond suggested a few years ago. King County Metro is in the process of developing interim plans for service that could benefit Belltown, but could be compatible with the Center City Connector.

Councilmember Herbold posed a question that went unchallenged by her colleagues. She asked city staff to determine “if a streetcar is a true transit infrastructure or if it’s more an economic development tool.” Indeed, nearly all transportation projects provide for economic development by their nature, but cities all across the globe rely heavily upon streetcars to carry large passenger volumes every day as a basic mobility tool. One of the best examples in North America is Toronto, which runs an expansive network and has doubled-down on more exclusive right-of-way for their streetcars.

Councilmbmer Herbold seemed overly excited at the prospect of cancelling the streetcar project and pushing funding to other transit projects. She followed on to note that her and some of her colleagues have been pushing expensive project elements for the West Seattle and Ballard light rail extension, so expensive in fact that non-Sound Transit funding would be required to foot the bill. An example of that is her personal crusade to tunnel from Avalon to Alaska Junction at an additional cost of at least $700 million, despite no noticeable ridership gains and operational efficiencies.

“We are going to be charged with identifying third-party funding for the preferred alternative,” Councilmember Herbold said. “That’s one of the things I’m going to be looking at and I’m hoping my colleagues on the Elected Leadership Group do as well.” She then said that it will need to be “third-, and fourth-, and fifth-party funding.” The reality though is there is no charge to waste gobs of money on lavish project elements.

SDOT reiterated that if the project is terminated, there are still contractural obligations that the city would be on the hook for. At this point, it is not clear what that number might be.

Councilmember Johnson then decided to use up a lot of oxygen with a long history of how the city even got here with the streetcar:

I would be remiss if I did not reflect on the last time that we had a major snowstorm in this city: 2008. You and I were both wrapping up a process that identified an alternative to what has just been opened [(the SR-99 tunnel)]. As part of that process, we had asked for and we’d received a commitment for from the state to receive $100 million for the city to construct a waterfront or First Avenue streetcar and a commitment to have the state legislature adopt a 1% motor vehicle excise tax to fund transit service. That first commitment never materialized. The second commitment we got passed by the legislature and got vetoed by the governor.

This conversation, you’ll forgive me, has been going on for a very long time and it’s an issue that I feel very passionate about because so many commitments have been made to get this project done and been walked back from, starting from those first conversations all the way back to 2007 and 2008. I appreciate the difficulty that the staff is in in trying to be very transparent with us about what the costs associated with this revision has been, but I reflect on that moment in 2008 where we had a $100 million and project we thought was going to be $75 million, and we never received those dollars. And so therefore the project could never get built, and here we are 11 years later in a very different scenario are having the same hard conversations.

Wrapping up his soliloquy, Councilmember Johnson urged state legislators crafting new transportation funding to remember their promises from so many years ago and make good on funding the streetcar project.

Noble then said that a funding proposal would soon be coming to help SDOT move forward on project design refinements and grant funding with FTA. With $500,000 budgeted for the year, identifying funding sources for the overall funding gap will also be necessary in the future.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.