Cities grow organically, by trial and error, sometimes with calculated assumptions made by planning experts. The Urban Village Strategy of the mid-1990s is one of those success stories providing added housing and increased diversity. Seattle is in the process of a new calculated assumption, requiring all development provide or pay for affordable housing in all projects citywide. The plan calls for upzones in the 27 urban villages throughout the city. These 27 neighborhoods are the city’s well of opportunity to supply housing growth. My neighborhood, the Aurora-Licton Urban Village (ALUV) will rezone a one-mile stretch of Aurora Avenue from auto-oriented and industrial commercial to residential mixed-use, providing capacity for 8,000 housing units along the RapidRide E Line, King County Metro’s highest ridership bus.

After defeating a barrage of neighborhood appeals, the Mandatory Housing and Affordability (MHA) Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) will move forward to the City Council. The next steps are adding amendments to enhance the plan’s goals. Aurora has as an opportunity to enhance this mission.

While ALUV’s housing stock has grown, it still lacks basic amenities to function as an urban village. Most of it isn’t walkable, there are no community spaces, and the stretch of Aurora, dedicated as it’s “Urban Village Main Street” looks nothing more than a wide road gash with parking lots, lowrise buildings, vacant or run-down blocks and proposals for self-storage facilities. The area was labeled “low access to opportunity” by the MHA EIS signaling a need to improve this stretch.

Rezone All of Aurora

The first suggestion is not an amendment. Instead, it’s a vote of confidence to the city’s current preferred option, rezoning the entire stretch. Auto-oriented commercial businesses oppose the upzone of Aurora and have requested a separate planning exercise, providing opportunities to downzone this area.

In 1994, when the urban villages were established, these businesses opposed rezoning Aurora. The city caved and while the residential neighborhood increased housing stock by 39%, Aurora added almost none of it and remained an area of low opportunity. From 1995 to 2010 job growth decreased by 15% along this stretch.

The MHA program reclassifies 9% of the city’s 1,500 acres of Commercial 1 and Commercial 2 zoning stock, totaling a paltry 140 acres. At the same time, 6% of the city’s 18,800 acres of Single Family zoning, a total of 1,128 acres, will be rezoned under MHA. The change to single-family zoning is seen as a minimal impact acceptable to make way for more housing. If the city believes this strategy, then rezoning 9% of Commercial 1 and Commercial 2 lands should be no issue.

The EIS preferred option will transform the entire one mile stretch of Aurora to Neighborhood Commercial, a zoning type that requires housing above the first level. The residents of this neighborhood have accepted their own zoning changes and ask for the same level of commitment by commercial land owners inside this urban village. We cannot afford to lose a single parcel. Each one brings hundreds of housing units and hundreds of thousands of dollars to build affordable housing stock in the city.

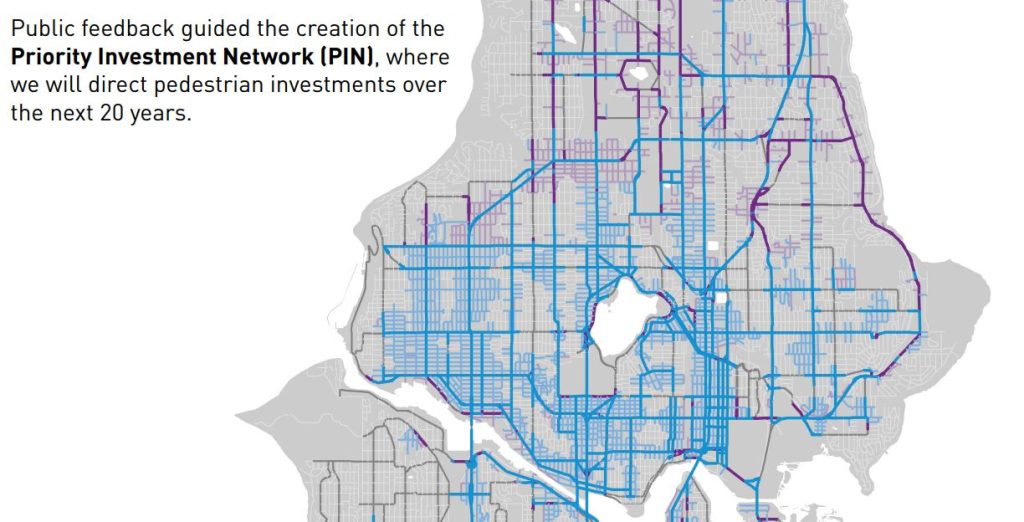

Amendment 1: Add Pedestrian Designation to All of Aurora

The city’s land use code adds requirements to Pedestrian “P” zones that provide walkable, safe environments for thriving commercial districts. Right now, only one block will be given the “P” designation along Aurora. Aurora is not safe to pedestrians, and needs upgrades to the safety of the street. Pedestrian zones promote street level retail, a program struggling in this area.

The Seattle Department of Transportation lists this stretch as an Urban Village Main Street. And judging from their illustration, the “P” designation will turn this into reality. This will go together with the land use changes and finally provide Aurora all the ingredients needed to succeed as a thriving business district.

Amendment 2: Offset MHA Fees with City Services Incentives

The city’s MHA program charges dollars per square foot on new development if payment-in-lieu is opted by the developer. This impact could increase costs by $300,000 in order to build a standard 300-unit mixed use project along Aurora’s “low” market designation. The fee could stall development as projects no longer pencil financially.

ALUV is an urban village but it lacks critical elements to survive as one. There is no library, no bank, no community center, no neighborhood elementary school, and much of the area lacks sidewalks. The west side of Aurora doesn’t have a park, a community garden or any children’s recreational area.

The city’s first amendment should directly pay 50% of the MHA fee back to the developer if they provide a library, community space, or park space. Waiving large portions of the MHA fee not only makes a project financially viable, it lowers costs to market-rate housing and retail, two problems the city faces in addition to providing affordable housing.

Amendment 3: Offset MHA Fees with Green Construction Incentives

The remainder of the MHA cost should be paid back if a developer constructs a project out of cross-laminated timber, provides green energy production, or is certified as carbon neutral or carbon negative structure. ALUV’s own local business, Dunn Lumber, would benefit from a mass timber construction requirement and provide building materials a stone’s throw from any job site in the neighborhood.

Cross-laminated timber construction can be carbon negative and utilizes young trees reaching full maturity as they absorb more carbon dioxide than a fully-grown tree (just picture a teenager’s eating habits & metabolism versus an adult’s). The replenishment of these trees helps the environment by accelerating carbon dioxide absorption, it helps local farms, it helps ALUV business, and it revitalizes this auto-oriented carbon generating history of Aurora into a new era of sustainability.

Rooftop solar panels are also vital and feasible, as no other building zone will exceed the 55- or 75-feet construction height available on Aurora. Solar energy generation could become part of Seattle City Light’s overall green energy program providing local jobs to this neighborhood. Seattle City Light even owns space in ALUV. Residents would benefit from municipal green jobs directly in the neighborhood.

Amendment 4: Family Sized Units Incentive

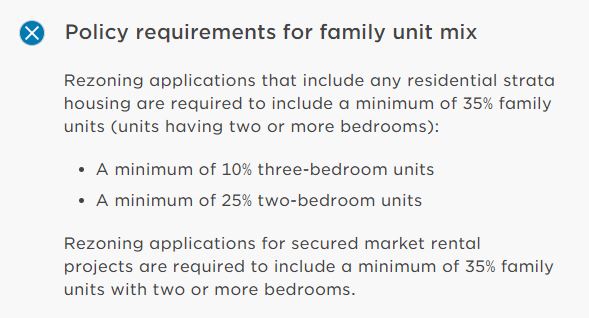

In addition to neutralizing MHA’s cost for providing neighborhood needed amenities and sustainable construction methods, the city should amend a financial payment for projects providing either 50% two-bedroom units or 25% three-bedroom units. Seattle may be a city of smaller households, but families should still be encouraged to live in dense urban environments.

With a 25% MHA fee matching subsidy, total incentives would become 125% against the charged MHA fee, creating a substantial discount encouraging new developments along Aurora. This would build housing where we should, build densely, and provide services and housing along corridors well served by mass transit. The State of Washington even provides transit-oriented development (TOD) incentives in addition to these proposals, creating even more development interest along this forgotten stretch.

The other obvious amendments would request for taller buildings, denser upzones, required unit mixes or expanded boundaries. But those aren’t necessary in this neighborhood. With 57 acres of largely underutilized land along the highest bus ridership in the city, the opportunity along Aurora Avenue has never been better. Providing incentives that discount the project costs can point development where it’s desired. Aurora land is already cheap. Amendments should encourage developers to locate this opportunity, provide housing, pay for affordable housing, and add to the neighborhood in ways it’s greatly needed. Environmental and social incentives would provide a new direction for the city’s most forgotten thoroughfare.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.