We’ve seen a lot of wistful eulogies for the Alaskan Way Viaduct. This is not one. I hope the viaduct’s concrete spirit burns in highway hell next to a bunch of other overbuilt freeways that have fueled massive carbon emissions and paved our way to a climate change crisis.

For 65 years, the viaduct made life worse in Seattle, belching out pollution, blasting an unceasing roar of 100,000 daily vehicles, jumpstarting White flight, and transforming the waterfront from a bustling port blending seamlessly with the city to a forgotten eyesore. Imagine the beauty of Elliott Bay’s beach and tideflats before White settlement! When did replacing that beautiful scene with 60 feet of concrete to carry 100,000 honking cars start to seem like a good idea?

The last motorists drove the viaduct on Friday night–some of them squealing their tires and blaring their horns in a car culture salute to a fallen monument to motoring. For three weeks these motorists will have to make due without a second freeway running through Downtown Seattle. And then the new monument to motoring–the $4 billion SR-99 double-decked deep-bore tunnel–will open. The Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) is already running ads on TV begging Puget Sound Region motorists to try the tunnel once it opens and take advantage of free trial period. How’s that for climate action!

The Quiet Aftermath

On Saturday it was strikingly serene on the Seattle waterfront. Instead of thousands of rumbling cars, there were people strolling and biking on the viaduct. Many have lamented the loss of the view the viaduct provided from the convenience of a speeding car, but people were still enjoying the view this weekend at a leisurely pace–the best pace to enjoy a view and not one driving permits. Stop-and-go traffic is not leisurely even if it is slow.

The authorities had secured the on-ramps by Sunday, contending people ambling about the carless viaduct was dangerous–meanwhile 109 pedestrians died in crashes on Washington state roads with cars–but nothing to see there. The ultimate waterfront vision once the viaduct is torn down will include an “Overlook Walk” to replace the view being lost and make it better by making it walkable and complete with seating, trees, and flowers rather than a sewer of cars.

A Ticking Time Bomb Defused

There’s plenty of arguments against the viaduct even before mentioning the thing was a deathtrap the whole time because it was not engineered to withstand a major earthquake. We dodged a bullet, but barely. The 2001 Nisqually earthquake nearly did it in–and everyone on or under it, but thankfully it managed to stay standing–although major repairs were needed. Instead of immediately starting to dismantle the monstrosity to cut our losses, we set the dutiful engineers at WSDOT to the task of bracing the badly-shaken structure and motorists were driving on it again in no time.

Nonetheless, the experts told us it was a ticking timebomb, so state policymakers in their infinite wisdom went to work selling a bigger and better viaduct built to tough out an earthquake and tried to force it upon Seattle whether its citizens wanted it or not.

Resistance to Viaduct 2.0

Fortunately, Seattle stood firm and blocked another viaduct from being built along the waterfront. For a while–thanks to the efforts of Cary Moon and the People’s Waterfront Coalition–it even looked like we’d invest in transit instead of replacing the viaduct with a tunnel. That would have been something bold and not at all consistent with America’s signature cavalier attitude of barrelling toward a climate catastrophe with reckless abandon. As badly as car activists longed for another corridor to jam their cars in at high speed, a cut and cover tunnel was unpopular in Seattle–as a 2007 public vote proved.

God from the Tunnel Boring Machine

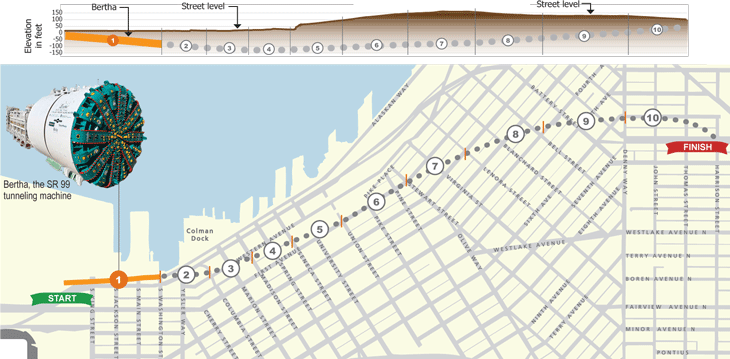

In stepped the Very Serious People and their real-life deus ex machina solution: a 57-foot-wide tunnel boring machine, the largest the planet had ever seen. Boring a tunnel that large hadn’t been tried before, and it would be extraordinarily expensive. (And that was before the massive 6,100-tonne machine broke and had to be disassembled and medevaced delaying the project by another three years–more on that later).

But a car megatunnel did speak car culture’s language and it had the backing of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and Democratic heavyhitters like then-State Senator Ed Murray and Governor Chris Gregoire. That deep-pocketed alliance was able to shepherd the deep-bore tunnel project and power it through a low-turnout August 2011 Seattle referendum that would have instructed the Seattle City Council to block its permits. The path to boring was clear.

Governor Gregoire dismissed the idea that the project was likely not to go according to plan or meet timelines as she criticized tunnel opponents as pessimistic. “There is no indication that we are going to be over budget,” Gregoire said in 2010.

But the Machine Breaks

And then the 99-meter-long machine broke just 1,083 feet into the 9,270 foot tunnel. In retrospect, it was incredibly lucky the machine broke so soon because it was possible to excavate the broken behemoth where it stopped on the waterfront. The same would not have been true if it broke later on with a highrise building overhead. Imagine if that had happened! The machine may still be stuck in a half-finished tunnel and the People’s Waterfront Coalition would have won by default. Or we would have torn out a few blocks of Downtown Seattle to retrieve it at astronomical cost.

How Much Will the Tunnel Project Cost?

The viaduct replacement tunnel budget sits at $3.3 billion, WSDOT secretary Roger Millar reiterated last week. However, that’s not accounting for earlier demolition of the southern viaduct portion in SoDo and the cost overruns related to the tunnel boring machine breakdown and the ensuing delays and repairs–which are sure to be litigated in court.

When all is said and done and litigated, the whole viaduct replacement project may end up costing close to $5 billion.

Litigating the Breakdown

Did the machine break down because it hit an eight-inch steel pipe (which, by the way, was left there accidentally by a WSDOT crew testing groundwater conditions) or because it was not built strong enough for the job? This question could decide who foots the bill for the overruns, and it’s still in dispute.

Getting dangerously in the weeds here, but if you ask an engineer, a boring-machine as large as the SR-99 one has fundamentally different physical qualities. Instead of the pressure being distributed in an even dispersal as happens in smaller boring machines (like those used to bore light rail tunnels), the cutterhead reaches 57-feet in diameter and the earth pressure is no longer distributed in an even fashion but instead concentrates in certain areas, making the boring machine much more prone to failure and in need of structural reinforcement. It’s telling that when the SR-99 tunnel boring machine was repaired, manufacturer Hitachi Zosen added thousands of pounds of steel reinforcement ot the cutterhead–ensuring the machine didn’t overheat and breakdown again. Perhaps they underbuilt the machine’s cutterhead in the first place, underestimating the earth pressure forces.

This wonky engineering dispute could ultimately decide what share of the overrun is paid by the manufacturer Hitachi Zosen, the contractor Seattle Tunnel Partners, WSDOT, the City of Seattle, and the various insurance companies backing each. If not for the steel pipe WSDOT left in the machine’s path, the liability would have fallen on the manufacturer more clearly.

Now, the case is likely to result in some sort of complicated cost sharing agreement with taxpayers taking a hit. But at least throughout the harrowing saga our leaders have proven that no matter the cost they’ll make sure you can drive through Downtown Seattle at high speeds and that you never have to contemplate a world with fewer cars. Climate action starts some other time.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.