One of the central promises made to voters who passed Seattle’s ambitious 2015 “Move Seattle” transportation levy was a robust commitment to expand Seattle’s sidewalk network into neighborhoods where there are now significant gaps.

When the levy was sent to voters, the Murray administration was so confident that they would be able to lower costs to build sidewalks by utilizing new strategies for creating pathways along neighborhood streets that they raised the target for the number of blocks completed from 150 (which would have only included traditional concrete sidewalks) to 250. The previous transportation levy, Bridging the Gap, had built 118 blocks of new sidewalks, but Move Seattle had to go bigger.

As we now know, most of the cost estimates that were used to plan projects for the levy were wildly optimistic, and increased project costs took their toll on the new sidewalk program also. In 2018 the program was one of multiple that the Seattle Department of Transportation or SDOT, under interim director Goran Sparrman, took a deeper look at to determine project viability. The verdict came back: 250 blocks was still doable, but the ratio of 150 blocks of traditional sidewalk to 100 blocks of lower cost pathways would have to change. In November, SDOT released a workplan detailing exactly how this would shake out: only 120 blocks on the workplan were permanent sidewalks along arterial streets and 130 were the low cost pathways.

In other words, Seattle’s $95 million new sidewalk program will only result in 120 blocks of new permanent sidewalks and 130 sidewalks that are not designed to be permanent.

If Seattle is to deliver on its goals of bringing sidewalk access to neighborhoods that have been lacking them for decades, delivering safe places to walk that are faster to build and cheaper to implement than concrete sidewalks will be essential. The city’s Pedestrian Master Plan assumes an average cost per block for traditional sidewalk construction at $350,000, and with tens of thousands of non-arterial streets missing sidewalks, it would take hundreds of years to fill in our current gaps.

After three years of adding sidewalks under Move Seattle, however, it’s worth looking at what the low-cost sidewalks have added to Seattle’s neighborhoods as SDOT’s leadership commits to delivering more of those blocks. Where Seattle builds sidewalks and of what type and quality they are should not be determined by an arbitrary number picked in advance of an election but rather the needs of its citizens and the goals that we have agreed upon as a community.

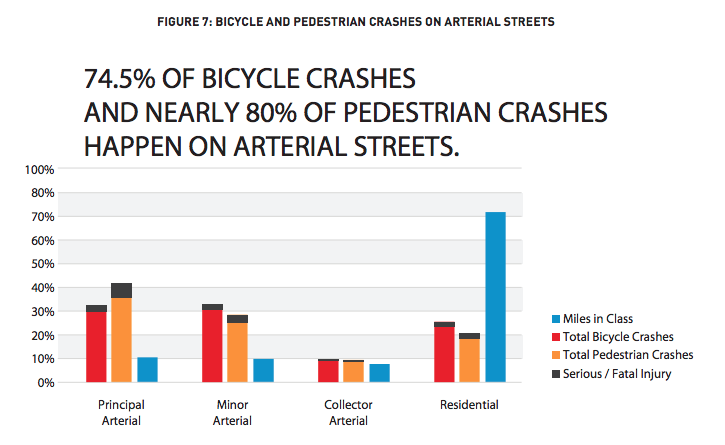

Committing to more “low-cost” blocks means moving sidewalk construction away from arterial streets, but arterial streets are where a majority of serious collisions occur. Despite composing less than 30% of Seattle’s roads by lane miles, the vast majority of collisions involving vulnerable users happen on arterials. The data shows collisions leading to injuries and deaths of people walking are on the rise and arterials should be where we’re focusing our safety efforts. In fact, the lack of progress expanding and improving sidewalk networks is likely a major reason pedestrian deaths are on the rise.

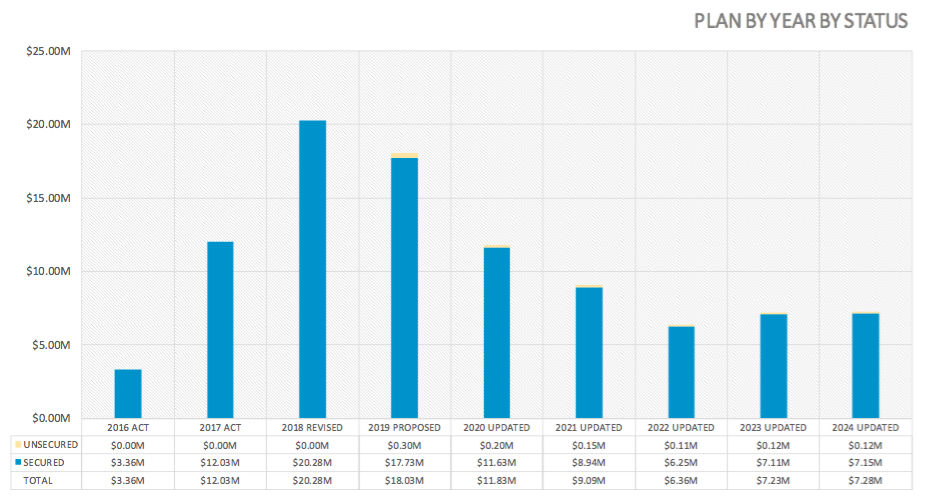

Increased costs are the reason that SDOT needed to reconfigure the ratio of low-cost sidewalks to traditional ones, but the program cost numbers overall are pretty concerning for pedestrian advocates. Despite the original estimate of $350,000 per block used in the Pedestrian Master Plan, the current plan for the 250 blocks is to spend $380,000, on average, per block, despite a majority of the blocks constructed in the plan being low-cost sidewalks, which had an original estimate of $100,000 per block.

In 2016, the first year of the levy, SDOT only constructed low cost sidewalks, 8.3 in total. But their records show they spent $3.36 million on those blocks, or $404,000 per block: four times the amount estimated in the Pedestrian Master Plan. In 2024, according to the work plan, SDOT plans to install six blocks of sidewalks to put the capstone on its 250 block plan, but calculates the cost to install those six blocks at $7.28 million, or $1.2 million per block.

But the real issue is: what is the quality of those additional blocks? It varies, but most of the blocks that have been built so far under the levy do not come close to matching the quality of a new traditional concrete sidewalk, by a long shot.

In 2016 and 2017, the first two years of levy spending, SDOT constructed a little more than 31 full blocks of low cost sidewalk, according to their work plan. A review of these blocks showed that only 7 of these 31 blocks created a new fully-accessible separated pathway where one did not exist prior, like the example below from NE 135th Street.

The majority of the blocks, 21 in all, already had a sidewalk, but the sidewalk was of low quality and in most cases flush with the road, leading to vehicles parking on or near it. The improvement that allowed these blocks to be counted as new low cost sidewalks was the addition of wheel stop barriers along the roadway, as shown below.

One notable block constructed in 2017 on 19th Ave NE was simply a painted line with a symbol of a person walking painted inside the line, no additional protection or separation added for people walking along that street.

SDOT is also perplexingly counting the newly constructed hillclimb at Yesler Terrace, a Seattle Housing Authority project, as two blocks of low cost sidewalks for the purposes of levy goals.

By contrast, the traditional concrete sidewalks constructed so far under the levy are just what you’d expect: new fully-accessible walking paths that will last decades, like the one below adding a second sidewalk to S Orcas Street in South Seattle, which will be a key connecting route between the future Graham Street light rail station and Dearborn Park International School.

The low cost sidewalk program appeared to offer an alternative to filling Seattle’s sidewalk gap from a budget that couldn’t possibly meet the need. But it can only do that if the facilities that it produces are high quality.

Furthermore, the original intent of increasing the sidewalk goal was to stretch the budget further beyond 150 blocks that the department knew it could complete. It was never to replace promised sidewalk blocks that could have been built if the goal had never been extended in the first place. At the very least, pedestrian advocates should urge SDOT to return to its original goal of 150 blocks, and then use additional funds to build high quality pathways where it’s able to, magic number be damned.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.