Last September, I led a 30-person deep bike ride from Ballard to Wallingford for The Urbanist. Ages ranged from four to mid-70s, we had family bikers, cargo bikers, and my wife hauled a friend who couldn’t ride because they had recently been hit on their own bike. It was an opportunity to talk about the history of zoning and land use in North Seattle.

I was approached to lead a North Seattle variation of Merlin Rainwater’s ‘Redline Ride’ –which my family took part in last spring. (I wrote about that excellent excursion here). There were a number of questions about how to obtain more info on these issues, and a number of people who weren’t able to join have asked for information as well, so I’ve put together a recap.

I think of Seattle as really having two distinct phases with regards to land use: pre-1923 zoning ordinance (PZO), and post-1923 zoning ordinance. Many of the neighborhoods and business districts we love so much were built before a zoning ordinance was written. The 1917 Seattle Building Ordinance was the last passed before the 1923 zoning ordinance, and it was a beautifully succinct document that covered land use and building code requirements. If you subtract the advertisements, it’s a stunningly massive 200 page tome. For reference, today’s Seattle Building Code is roughly 770 pages, and the Land Use Code is probably close to the same. Neighborhood design guidelines are not included in either of those.

Pre-zoning Seattle, multifamily housing was legal literally everywhere. Today, it is illegal almost everywhere. Height was regulated by street width (a method similar to Japan). The city was broken down into districts A through D, which had corresponding limits on height and building cladding, going from most fire-resistant to least. Generally, everything north of Denny, South of Holgate, and east of Broadway was the fourth district, which allowed any type of building, however, the three-story wood framed building was most prevalent.

The 1923 zoning ordinance, which Harland Bartholomew had a hand in crafting, introduced single-family zoning for the first time and made it illegal to building multifamily housing in most of the city (there was much more multifamily area than today though). With the onset of the automobile, parking requirements were eventually introduced, and then over the decades revisions to land use regulations saw increasing setbacks, reduced lot coverage, density limits, and reduced height limits.

Norm Rice’s Urban Village strategy took hold in the mid-1990s, with ‘neighborhood planning’ that was largely dominated by landowners and homeowners, severely limiting where new housing could go, and what it could look like. A 25% affordable housing requirement in the Urban Villages was killed by homeowners. And despite claims (almost exclusively by homeowners) of neighborhood planning being democratic, less than 2% of Seattle’s population today had any hand in crafting it. The results are highly inequitable, and our housing shortage today is largely because of it.

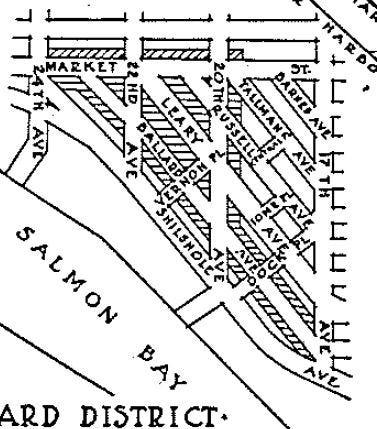

Ballard Ave

Pre-zoning (PZO): The historic core of Ballard pre-zoning was listed as a third district, which permitted fireproof buildings, mill buildings up to six stories, ordinary masonry buildings, one story frame business buildings, and two-story frame dwellings. It is interesting to note this means six-story buildings have always been legal in most of Ballard. Warehouses, lofts, and workshops all allowed 100% lot coverage on any lot.

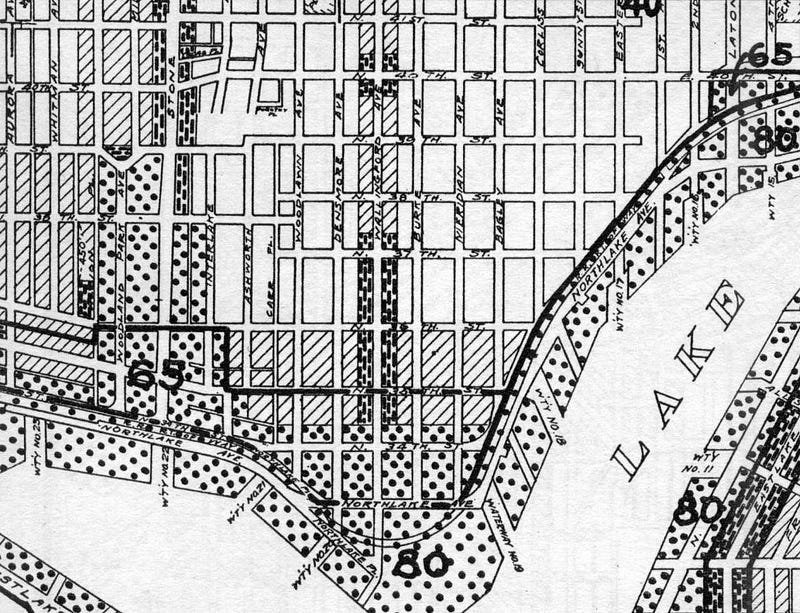

Zoning 1923 (or ’23 ZO): Most of Ballard Avenue zoned for commercial, with everything along the water being zoned for manufacturing (today, we label it Industrial). All of Ballard Ave and the waterfront were zoned for 80-foot tall buildings. Market was zoned for 65-foot tall buildings.

Today: None of Ballard Avenue or the waterfront are zoned for 80-foot tall buildings. Ballard Avenue is zoned for 65-foot tall buildings, but development potential is limited due to historic designation. Much of the Ballard Urban Village is still zoned for 65-foot tall buildings. The taller buildings we’re seeing today are not really out of step with what was legal a century ago in Ballard.

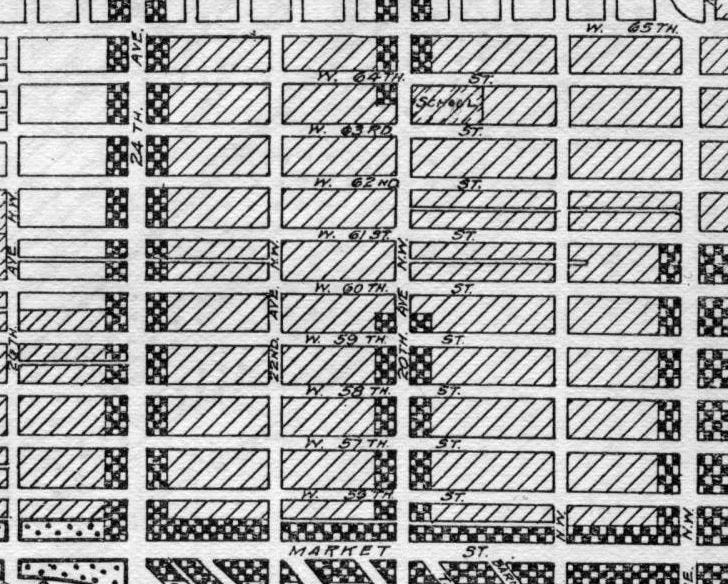

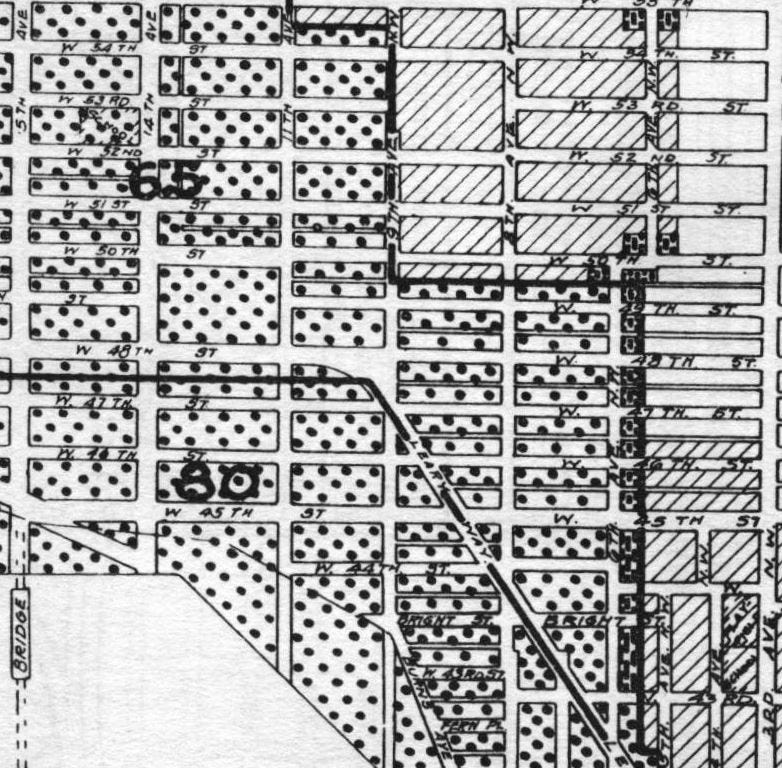

North Ballard

PZO: 40-foot tall multifamily buildings were legal for all of Ballard north of Market –even north of NW 65th St as there was no single-family zoning. Lot coverage varied from 73% to 100%. Setbacks were three feet, but could be less if masonry or other ‘incombustible or slow burning construction.’

’23 ZO: This area was zoned Second Residence District, which allowed 40-foot tall multifamily housing — there were no density limits, no limitations on forms of housing. From NW 60th St to NW 65th St, lot coverage was reduced to 35% (45% if corner lot), with 15-foot rear and three-foot side, and five-foot or 10-foot front yard setbacks introduced. South of NW 60th St, lot coverage was limited to 60% (70% if corner lot), with similar with 15-foot rear and three-foot side, and five-foot or 10-foot front yard setbacks.

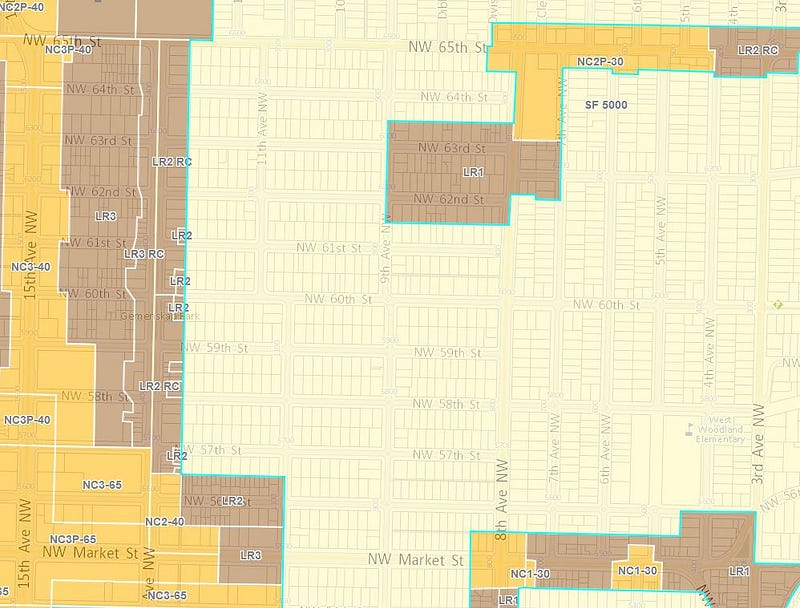

Today: LR1/2 (Low Rise 1 and 2 zones) building height limits vary from 25 feet to 35 feet by housing type (see City of Seattle Low Rise handout). Setbacks are five feet to seven feet for front and side yards, rear setbacks vary from zero feet to 15 feet. There are max facade lengths, which force more complex building forms than previous land use codes required –as well as density limits for all types, and design review as well. The zoning today is less permissive than even what was allowed under the 1923 zoning ordinance. Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) rezones are slotted to add another story or two of capacity to the Urban Village if it passes according to plan in 2019.

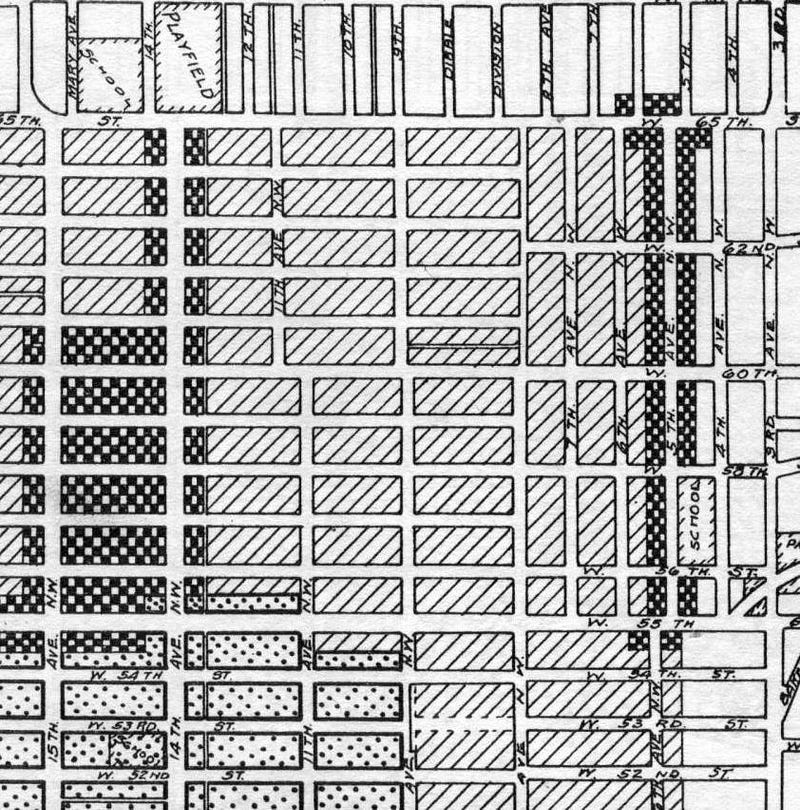

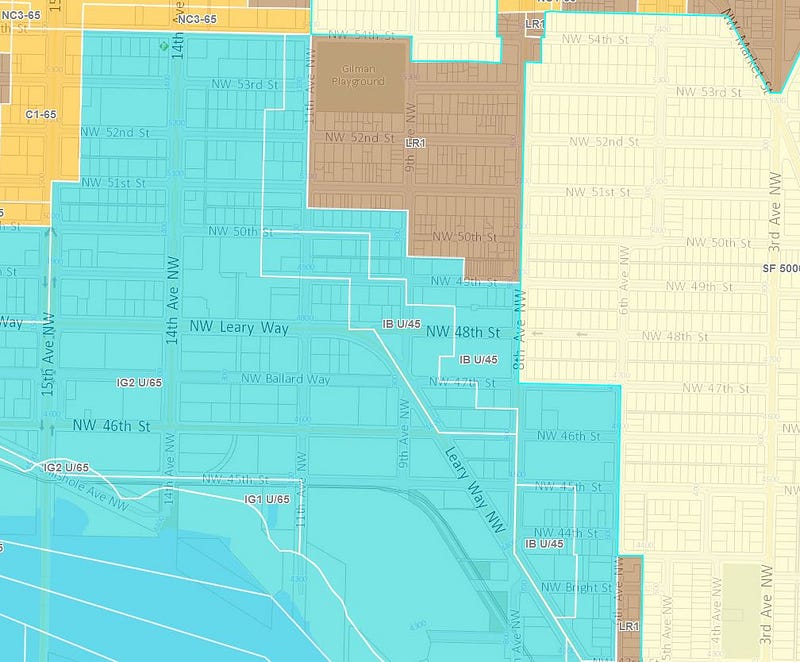

West Woodland

We stopped on 14th Ave NW, former streetcar route, at Gemenskap Park, which was funded by the 2008 parks and Green Spaces Levy.

PZO: Same as North Ballard, there was no single-family zoning anywhere and multifamily housing was legal everywhere.

’23 ZO: 14th Ave NW area was zoned for business due to the streetcar, and everything east to 6th Ave NW was zoned Second Residence District, which allowed 40-foot tall multifamily housing — there were no density limits, or limitations on forms of housing. Lot coverage of the Second Residence was reduced to 35% (45% if corner lot), with 15-foot rear and three-foot side, and five-foot or 10-foot front yard setbacks introduced.

Today: 175 acres where dense multifamily housing was once legal, now only allow detached luxury housing. Subsequent land use revisions saw this multifamily land downzoned to duplexes, and ultimately, today, nearly all of this neighborhood is zoned Single Family. Because of this, there are a number of existing, non-conforming multifamily homes that really have little protection from being replaced by a two-million-dollar single-family home. Sightline had a really great piece on the hidden multifamily housing in neighborhoods like this, and somehow these neighborhoods aren’t destroyed.

Gilman Park

PZO: Same as North Ballard, there was no single-family zoning anywhere and multifamily housing was legal everywhere.

’23 ZO: 40-foot high Multifamily to north and east, largely zoned commercial with 65-foot height limits to Leary, and south of Leary, Manufacturing with an 80-foot height limit.

Today: Single Family to the north of the park, multifamily just one block east, and two blocks south. South of that is Industrial Buffer with a 45-foot height limit, and Industrial General with a 65-foot height limit south of Leary, and west for two blocks, roughly. There are two exceptions for housing in the Industrial Buffer zones — artist live/work lofts, and (1) 800-square-foot caretaker’s unit per parcel. Interestingly, because non-conforming housing was allowed to remain in Industrial areas as long as the use never changed — this is how the Edith Macefield house came to be. It was built in 1900, over two decades before the zoning ordinance. Also worth noting — there are many single story retail buildings being built in the Industrial lands with 65-foot height limits – this seems less than optimal given our housing crisis.

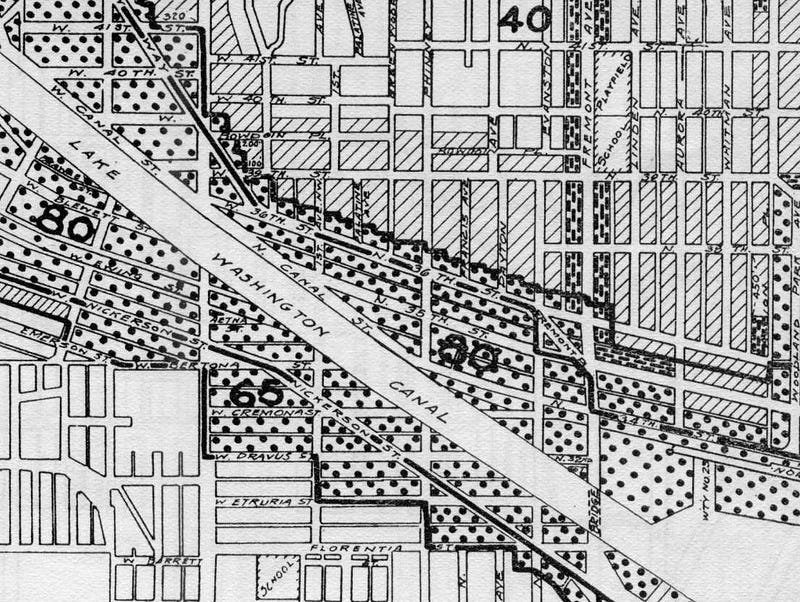

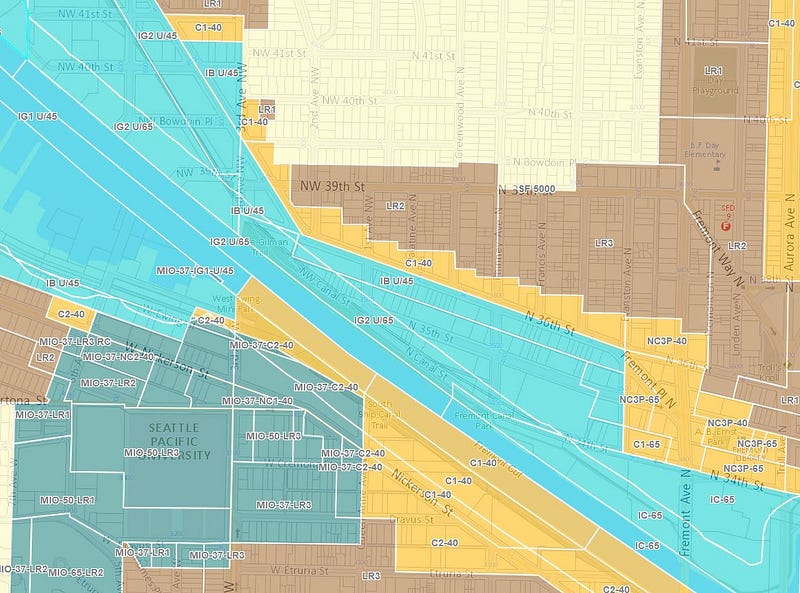

Fremont

PZO: Same as North Ballard, there was no single-family zoning anywhere and multifamily housing was legal everywhere.

’23 ZO: 40-foot high Multifamily at northern portion of Fremont Urban Village, Commercial zoning with a 65-foot height limit at N 36th St, Commercial zoning with an 80-foot height limit south of N 36th St, and Manufacturing with an 80-foot height limit west of 3rd Ave N and around the Fremont Bridge.

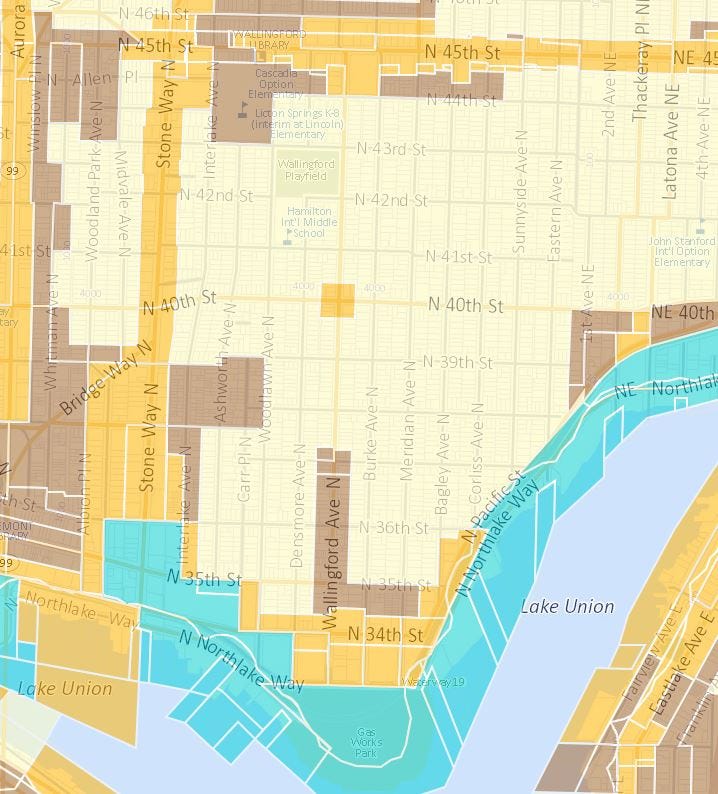

Today: The Fremont Urban Village is about 60% of what the city proposed— with all of the area south of the Ship Canal being eliminated, and none of the zoning being changed during the ‘neighborhood planning’ process. The C1-40 is Commercial zoning with a 40-foot height limit north of N 36th St. The Commercial zoning between the canal and 36th eventually gave way to Industrial General and Industrial Buffer (imagine, we could have had 80-foot high mixed use buildings for these blocks). The LR2 zone is less dense housing than what was allowed under the 1923 zoning ordinance, but LR3 in the Urban Village is more intensive.

Wallingford

PZO: Same as North Ballard, there was no single-family zoning anywhere and multifamily housing was legal everywhere.

’23 ZO: 40-foot high Multifamily south of N 36th St, Commercial and residential zoning with a 65-foot height limit south of N 35th St, and Manufacturing with an 80-foot height limit along the waterfront.

Today: Much of Wallingford has been downzoned from what was legal a century ago. Wallingford Avenue, which was zoned for multifamily housing on either side, and south of N 36th St were downzoned in the 1980s by homeowners who wanted to keep students and workers out of their neighborhood. If you’re interested in learning more about the pernicious land abuse in Wallingford, check out my article on Sightline, ‘the Narrowing of a Neighborhood’. Just last year, the anti-renter Wallingford Community Council submitted a comp plan amendment to eradicate half of the Wallingford Urban Village — so we’ve got a long way to go to reverse this land abuse.

The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History project has a section on Racial Restrictive Covenants with a few interesting notes on North Seattle.

“The maps suggest little difference in the demography of Wallingford, where no covenants have been located, from the demography of Ballard, Loyal Heights, and Greenlake, where they were common. This reemphasizes the point that social enforcement of segregation was every bit as important as legally enforcing deed restrictions. (Emphasis mine)”

The ride ended at Gas Works Park, with an impromptu (but poignant) statement by Merlin Rainwater, who had lead the redline ride through the Central District, about how these issues worked in parallel to create and exacerbate segregation. It’s important to understand how this legacy affects land use today — and specifically, how keeping affordable housing from 85% of the land where housing is legal — is compounded by this history. Eradicating single family zoning, as Minneapolis just did, won’t solve our housing crisis. But it is one of many steps needed to start down that path.

Mike is the founder of Larch Lab, an architecture and urbanism think and do tank focusing on prefabricated, decarbonized, climate-adaptive, low-energy urban buildings; sustainable mobility; livable ecodistricts. He is also a dad, writer, and researcher with a passion for passivhaus buildings, baugruppen, social housing, livable cities, and car-free streets. After living in Freiburg, Mike spent 15 years raising his family - nearly car-free, in Fremont. After a brief sojourn to study mass timber buildings in Bayern, he has returned to jumpstart a baugruppe movement and help build a more sustainable, equitable, and livable Seattle. Ohne autos.