A new report by the Seattle Planning Commission highlights how increasing density through “missing middle” housing could create a more diverse, equitable, and sustainable city.

As the closure and demolition of the Alaskan Way Viaduct grows imminent, it might be time for the City of Seattle to say good bye to another 1950’s relic: single-family zoning.

Thus goes the central argument of the Seattle Planning Commission’s report “Neighborhoods for All: Expanding housing opportunity in Seattle’s single-family zones” published on December 3rd.

The report describes how single-family zoning established in the 1950’s continues to prevent new development from creating diverse, walkable, and livable urban neighborhoods. It also explains how older development patterns found in many of Seattle’s most desirable neighborhoods may provide a key to solving current problems related to affordability and equity. The Seattle Planning Commission consists of 16 members, seven appointed by the mayor, seven by the Seattle City Council, one by the commission itself, and one Get Engaged young adult member.

Historic neighborhoods such as Wallingford, Queen Anne, and the Central District first developed around streetcar lines as compact walkable centers that incorporated both commercial activity and a flexible mix of housing.

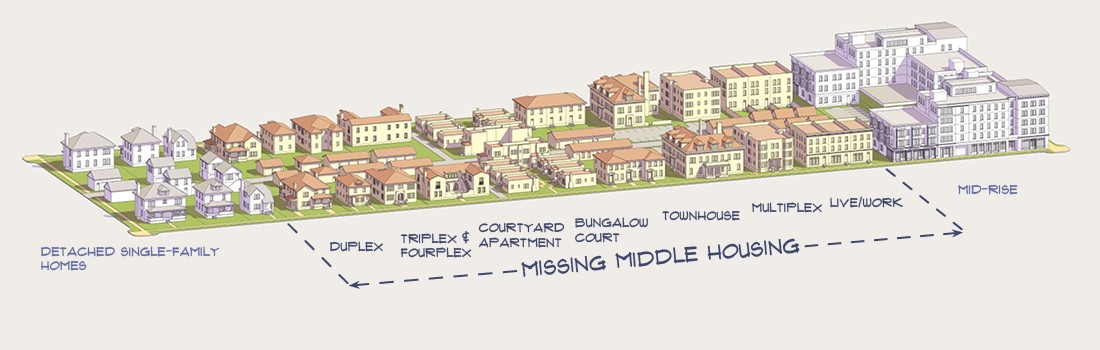

This was because Seattle’s early zoning permitted construction of “missing middle housing” such as accessory dwelling units (ADUs), duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings. These early development patterns were critical for establishing the density necessary to create vibrant, transit-oriented neighborhoods.

However, downzones passes in 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s made it illegal to build such small multi-unit dwellings in most of the city. Implementation of the “Urban Village Strategy” in the City’s 1994 Comprehensive Plan further directed new development into the small amount of land zoned for multi-family use.

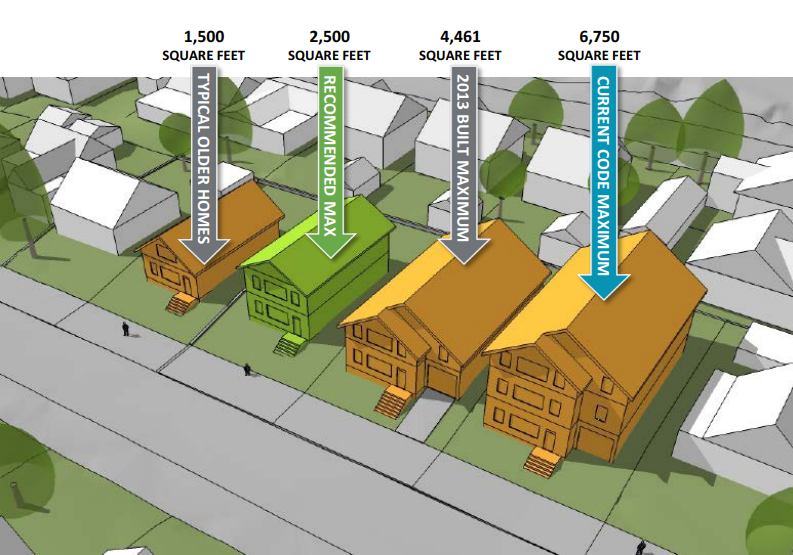

With roughly 75% of available land reserved for single-family lots, despite the city having added more than 180,000 residents, some single-family zoned areas of the city have actually declined in population since the 1970’s. At the same time, since 1900 the average size of a single-family home has increased by 1,000 square feet.

Current zoning allows for small scale residential dwellings like duplexes on only about 12% of available land in Seattle. This has reduced housing choices to basically two categories: high-cost detached houses in lower density areas and apartments in buildings with 20 or more units, generally in the city’s densest areas and along arterial roads with heavy traffic.

“Our current approach to zoning has created a bifurcated city, where two-thirds of residential land is off limits to all but those with the highest incomes,” said Tim Parham, chair of the Planning Commission. “The fundamental goal of this report is to encourage a return to the mix of housing and development patterns found in many of Seattle’s older and most walkable neighborhoods, thereby giving more people a wider array of living options.”

According to the report, creating more housing options at different sizes and price points would increase housing access for people of all races, incomes, and stages of life.

The report contains a list of suggested zoning changes, which the Planning Commission labels as strategies. The goal of these strategies is to “allow gradual, incremental reintroduction of historic building patterns” as Seattle continues to grow.

Proposed Strategies

- Expand all established urban villages to 15-minute walksheds from frequent transit.

- Promote the evolution of Seattle’s growth strategy to grow complete neighborhoods outside of urban villages.

- Establish new criteria for designating and growing new residential urban villages shaped around existing and planned essential services.

- Rename “Single-Family” zoning to “Neighborhood Residential.”

- Establish a designation that allows more housing types within single-family zoned areas near parks, schools, and other services.

- Develop design standards for a variety of housing types to allow development that is compatible in scale with existing housing.

- Revise parking regulations to prioritize housing and public space for people over car storage.

- Allow the conversion of existing houses into multiple units.

- Allow additional units on corner lots, lots along alleys and arterials, and lots on zone edges.

- Incentivize the retention of existing houses by making development standards more flexible when additional units are added.

- Reduce or remove minimum lot size requirements.

- Create incentives for building more than one unit on larger than average lots.

- Limit the size of new single-unit structures, especially on larger than average lots.

- Retain and increase family-sized and family-friendly housing.

- Remove the occupancy limit for unrelated persons in single-family zones.

Many of these strategies are similar to those put forth in the City of Portland’s ambitious “Residential Infill Project,” which was initially proposed two years ago and has undergone some changes in response to comments from the public. Recently another round of public review on the proposal was concluded. The Portland City Council is expected to vote the proposal in summer in 2019.

The Seattle Planning Commission acknowledges that due to the controversial nature of some of their suggestions, their proposal will likely face resistance. In the FAQ, the Planning Commission is careful to state that it is an “advisory body” and “any legislation that may be generated from these strategies will be developed by City staff” as part of a “process [that] will provide opportunities for community input.”

With the release of “Neighborhood’s for All” the Planning Commission has initiated an important conversation on what is still a taboo subject for many Seattleites: a move away from single-family zoning to more flexible “neighborhood residential zoning” that encourages more diverse housing types.

And it’s possible that in combination with the recent decision to complete an analysis of the race and equity impacts of the City’s Urban Village Growth Strategy, this might be the beginning of an earnest, citywide discussion on whether or not single-family zoning should be relegated to the past.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.