In a previous installment, I wrote about the strain put on sidewalks when cities privatize, sell off, fail to maintain, or don’t care to provide proper public spaces in the first place. I argued that the reductions in public space we observe in cities across the U.S. undermines democracy because it reduces the opportunities we have to meet others so as to debate, define, and take up the projects resulting in a good life. Simply, without public space we can’t have a functioning democracy.

Sidewalks comprise part of the physical infrastructure that brings about the relationality among neighbors on which democracy depends. This relationality isn’t merely the result of spaces and places, however—rather, it depends on the sponsorship of institutions and organizations which organize and create opportunities for neighbors to meet and be together.

Building on the existing knowledge we have regarding the importance of physical infrastructure to the democratic project, Eric Klinenberg, Professor of Sociology and Director of the Institute for Public Knowledge at NYU, has recently made a case for recognizing the value of “social infrastructure” in civil society. Klinenberg defines “social infrastructure” as “the physical spaces and organizations that shape the way people interact.” In a sense, it’s not enough to have physical spaces in which to, potentially, meet our neighbors, it’s also important to have institutions offering and organizing opportunities for people to come together.

Tacoma, as I’ve written, enjoys many public spaces—it offers the needed physical infrastructure in the form of parks and plazas required to sustain a thriving community. But what about social infrastructure? Are there organizations and institutions creating opportunities that, combined with the availability of physical spaces, promote civic engagement?

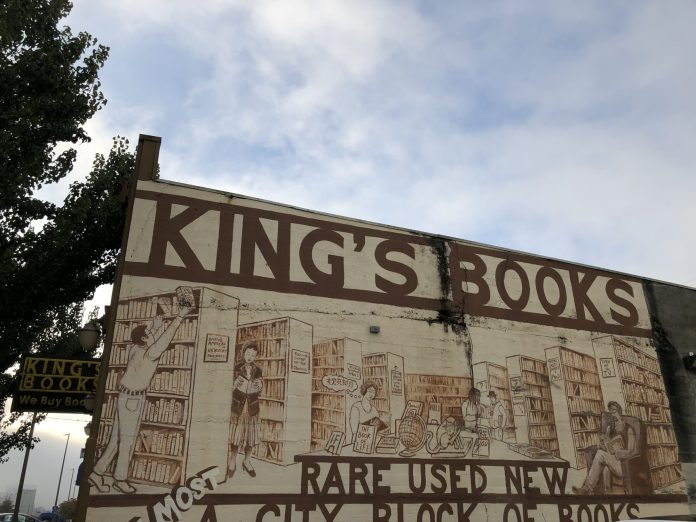

Klinenberg names public libraries and bookstores among the institutions and organizations that, together with public spaces, make up a city’s public infrastructure. These are the types of spaces where people can “gather and linger,” where newcomers and long-standing members of communities meet and create the types of networks that bolster life.

In my short time in Tacoma, I’ve been provided with opportunities to “meet and linger” with other Tacomans in order to consider our existing social infrastructure, and to give input about how it might be strengthened. Two of these came as a direct invitation from institutions, the Tacoma Public Library and from Metro Parks Tacoma. The initiatives to which Tacomans are being invited to consider and provide input into reflect the direct benefits a strong social infrastructure provides a city and its constituent communities.

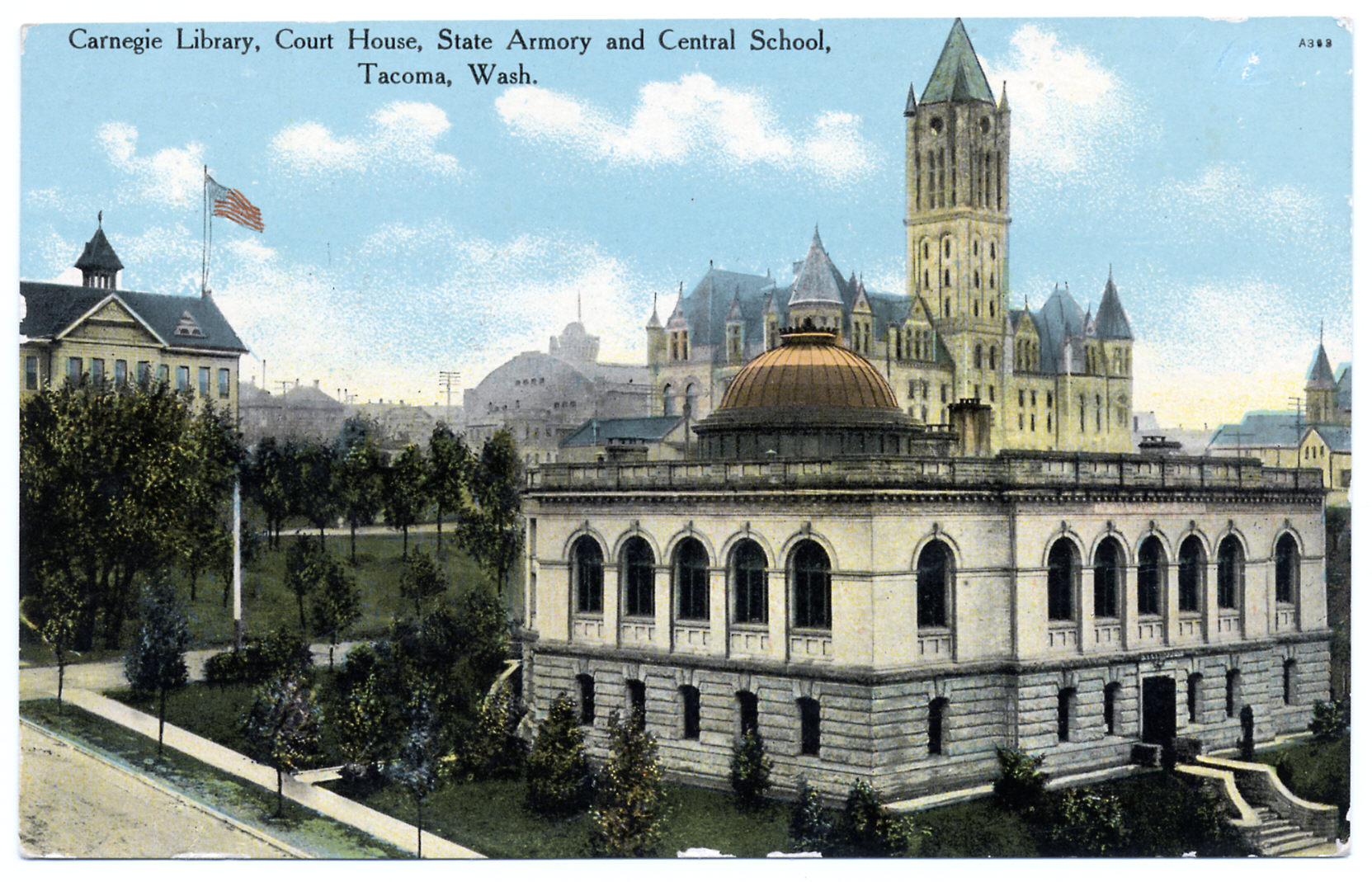

First, the Tacoma Public Library. From early September through early November, the Tacoma Public Library is hosting a series of conversations across the city “to better understand people’s aspirations for our community.” The “Libraries Transform Tacoma” initiative, part of a larger initiative organized by the American Libraries Association, has as a goal to encourage and promote dialogue and deliberation among people who share concerns about communities and want to strengthen communities.

Notably, the conversations the Tacoma Public Library are hosted in a variety of places and spaces across the city, including churches, parks, and academic institutions. As such, these conversations demonstrate the value of social infrastructure—physical spaces and organizations coming together to shape how people interact, and which promote civic engagement and civil society.

Next, Metro Parks Tacoma. Metro Parks is taking the opportunity to make physical infrastructure improvements to the city’s waterfront to engage and strengthen the city’s social infrastructure. Through the “Envision our Waterfront” initiative, Metro Parks is creating an opportunity for Tacomans to “gather and linger” over an issue of concern: how to make improvements to a space that is degraded and will continue to degrade as a result of saltwater and rising sea levels.

The concerns Metro Parks faces in relation to the waterfront and Ruston Way are technical and complex. The types of improvements needed require the expertise of engineers, city planners and managers, and environmental scientists. A city and its park district could be forgiven for reserving its efforts and for allocating its resources to getting technical experts to agree on a plan that makes the waterfront safe for continued use. But Metro Parks recognizes that there are other stakes present, as well as other stakeholders.

As a public space, the waterfront and Ruston Way are an important part of the city’s social infrastructure, and therefore, an opportunity to make physical improvements is also an opportunity to re-envision its current and potential social function and possible uses. By inviting Tacomans to take part in the visioning and planning process, Metro Parks is strengthening the social infrastructure of the city.

There are other examples of Tacoma’s social infrastructure besides these two, including King’s Books on St. Helens in the Stadium District, and The Grand Cinema a few blocks south. King’s Books hosts a number of book clubs that provide opportunities for neighbors to “gather and linger” over a books exploring myriad interests and concerns. There’s a book club for readers interested in LGBTQ experiences, for Spanish-language readers, and for readers interested in banned books.

The Grand Cinema, in addition to offering programming that centers independent and international film, much of which features and explores social justice issues, screens “Meaningful Movies” at no cost. These programs are meant to assist “neighborhoods, groups and individuals organize, educate and advocate using the power of social justice documentary film and relevant conversation to build positive and meaningful community and a more just and peaceful world.”

That these institutions and organizations exist in Tacoma, and that they continuously provide opportunities for Tacomans to meet and interact with one another, has given me a sense of place and pride already. These opportunities have also given me a sense that I share goals and aspirations with many of those around me.

Early in September, I spent time in a branch of the Tacoma Public Library as I finished preparing for the classes I would soon be teaching. My time there coincided with the last days of the teachers’ strike. The value of public libraries was directly observable then: in addition to the expected patrons (people needing internet access, job search assistance, a comfortable place to study, or a place to pass time), there were dozens of children browsing titles and socializing. Many were there with older siblings or with grandparents. I observed what could have been a teacher or a caring relative taking time to tutor a student who, perhaps, couldn’t afford to miss out on days of instruction.

Klinenberg’s New York Times’ piece cites a 2016 Pew Research Center study which revealed that “about half of all Americans ages 16 and over used a public library in the past year, and two-thirds say that closing their local branch would have a ‘major impact on their community.’” At certain times—like when there’s a teachers’ strike—it’s easier to appreciate a finding such as this. Do we see the value of our city’s social infrastructure when there isn’t a situation that directly affects us?

Klinenberg claims that “libraries are being disparaged and neglected at precisely the moment when they are most valued and necessary.” This echoes the argument I made about sidewalks in a previous installment. Like sidewalks and the physical infrastructure they comprise, libraries have fallen out of favor among those who can’t easily ascribe a market value to them. But we need libraries just as we need sidewalks. Without them we risk our very way of life, our democracy.

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist's board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.