But can the soul of the old Victorian house live on in a new mixed-used building?

According to modernist architect and urban planner Le Corbusier, “A house is a machine for living in.” This philosophy unpinned his collection of essays, “Towards an Architecture,” in which he put forth an impassioned call for viewing homes (and cities) as “tools of life,” demanding a “rebirth of architecture based on function.”

As an idiosyncratic Victorian grand dame, there was probably nothing Le Corbusier would have admired about the old house that served as home to writing nonprofit Hugo House for more than twenty years.

But with its odd angles and embellishments, the building did project an aura of mystery over the east end of Cal Anderson Park, and while the cramped rooms may not have been optimal for living, the Victorian design offered diversity in shape, size, and use that was perfect for finding space to dream.

These days a stroll through Seattle can feel like journey though a city scrubbed of its past. Built in 1902, the old Hugo House stood as a rare exception, which was why when property owners announced their decision in 2015 to demolish the property and replace it with a new mixed-used building, anxiety spiked around what the demolition meant for the both future of the nonprofit and the character of the city.

Fortunately, the property owners committed early on to making a place for the Hugo House nonprofit in the new building, easing some fears about what the loss would mean for the organization’s future.

But questions remained about impact to the neighborhood’s character and community. Located within the Pike/Pine Conservation Overlay District, developers were required to consider how the new building would fit into existing architectural patterns and land-use trends.

The Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) has identified Pike/Pine’s “auto-row” warehouse architecture as a defining feature of the district’s character. In their proposal for the new mixed-used building, architects Weinstein A+U described their design as “a modernist reinterpretation of the auto row aesthetic,” thus ensuring the ghost of the Victorian house would not live on, at least not in the exterior structure.

Creating a New Home for Writers

The goal of the partnership between NBBJ architects and Hugo House was to design a new interior space that only not better accommodated the organization’s practical purposes, but also retained the features of the old Hugo House that had made it such a nourishing space for writers.

This demanded recreating soul of the old Victorian house within a space hemmed in by many constraints. The new space would occupy only half of the residential building’s ground floor–and the structure’s core and shell were already designed.

“This was actually one of our more intimidating projects,” said Ryan Muellinx, partner at NBBJ. “Hugo House was very nervous about what happens when you take this history and put it into something that is new and very removed from what they had.”

To succeed, NBBJ would need to go beyond creating a usable physical space for Hugo House. The space would need to feed and inspire the community’s creative spirit, honoring the memory of namesake Richard Hugo, who in his book The Triggering Town wrote about how distinctive places prompt people to pause, reflect, and question–all essential parts of the writing process.

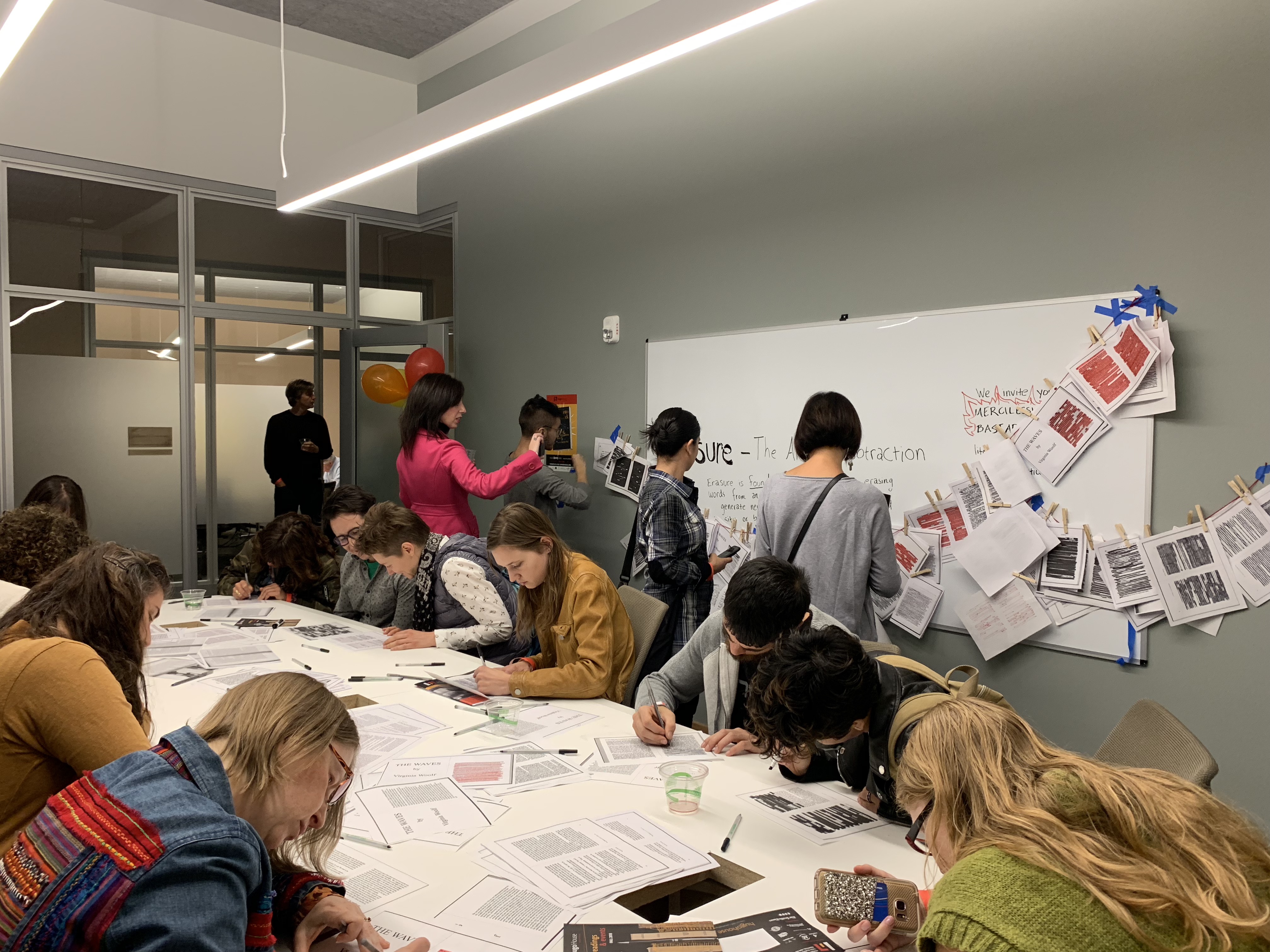

A team of over 40 NBBJ designers brainstormed with Hugo House leadership, creating a design intended to be eccentric, but also efficient, heeding limits in budget and space.

Features such as non-aligning walls and stairs to nowhere were intended to capture the eclectic nature of Hugo House’s character. While skylights projecting quotes from writers, such as Richard Hugo, as well as a new bar constructed from the floorboards of the old bar room, offered history and memory.

As a whole, the design elements were intended come together to create a composition that engages in constant play between what is open and public and what is intimate and private.

The uses of the space will change depending on the preferences of the occupants, so that just as in the old Victorian house, people will have many opportunities to “find their own spot.”

“We live in a world where a lot of our poetry starts on paper but faces its truest test in the physical realm,” Mullenix said.” And we know our work is successful when our work encourages the occupant, just like a reader with a book, to visit the space again and again.”

With its ADA accessibility and bathrooms open to all genders, the design also conveys the welcoming spirit of Hugo House as an organization. “The idea was to be inclusive, contemporary, and progressive–an attitude that Hugo House conveys outwardly,” Muellinx said.

A Positive Response from the Community

The new Hugo House has been open for a few weeks, and so far the response from the community has been overwhelmingly positive.

“It is exciting and exhilarating to be in a space with so many other people who care about the possibilities a community of ideas can provide,” said writer-in-resident Kristen Millares Young. “It’s also a place where I can go into the heart of Seattle and be at home as a writer. I don’t know that I ever expected that.”

As a writer, teacher, and performer, Young loved the old house, but was also very aware of its limitations.

“More than 1,000 people came to the opening event,” said Young. “It’s wonderful that the building can accommodate a crowd of that size because it presents really exciting possibilities for future programming.”

While the built environment surrounding Cal Anderson Park certainly feels different with the absence of the Victorian house, it is clear that the new space is serving the Hugo House community. In that way it has become a tool for many things: life, memory, creativity, progress — and maybe even history–all which are soulful in their own ways.

“I was attracted to the project because of what Hugo House stands for,” Muellinx said. “You have incredibly creative people there. We are always looking for ways to better connect with our communities and this allowed us to in a really joyful way.”

Young is optimistic about what the future will bring. “There is a palpable sense of anticipation about what the new Hugo House means for our community moving forward,” she said. “I think it will mean a lot.”

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.