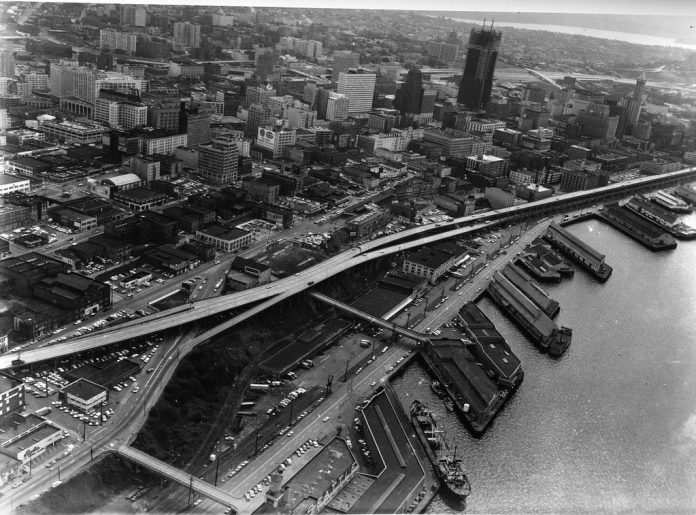

This week we learned that the Alaskan Way Viaduct will close permanently on January 11 of next year, with a three-week gap between the closing of one highway and the opening of another, the long-delayed deep bore tunnel connecting SoDo and South Lake Union. We’ve known this has been coming for a very long time, and the anticipated increase in congestion as 90,000 daily trips that currently utilize the freeway blocking our city from its waterfront find another route or mode.

The viaduct coming down was one of the main impetuses for the One Center City planning process, a meeting of the minds at the regional transit agencies. The outcome of that process was mainly the status quo, and so as we hurtle toward what is anticipated to be a major weeks-long traffic jam, it’s worth noting what tools the city is utilizing to prepare for this event.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) posted an update to its blog after the announcement of the viaduct closure this week: “Here’s what we’re doing to help you get around downtown.” In it, the department lays out its five strategies for getting people around the center city:

- Transportation system monitoring and real-time management.

- Investments in transit.

- Reducing drive-alone trips downtown.

- Managing construction projects in the public right-of-way.

- Working with commuters, employers, visitors, and Seattleites on their commute.

But it’s clear that pretty much the only tool in the toolbox at SDOT under Mayor Jenny Durkan is trying to move more vehicles, mostly with one or two people in them, though our limited downtown streets at the expense of those who chose alternate options.

The post does not mention any additional resources for people who might want to switch to walking or biking. A proposed bike lane on 4th Avenue was cancelled early in the Durkan administration for this exact event: the potential to carry more cars on that street apparently outweighed the number of people that could be carried by a bike lane there. No bicycle facilities will be planned to help get people through downtown for this extreme traffic event.

As for the first item on the list, “transportation system monitoring and real-time management,” it’s not hard to find an example of what that looks like in practice. For the most part, it is a prioritization of cars above other modes, namely people on foot. The Mercer corridor currently gets a high level of scrutiny from the municipal tower traffic center, to the detriment of people just trying to walk there. Having a 24/7 operations center constantly finding ways to get cars through as many intersections as possible is a fool’s errand. And once again, the focus here is on what can be done to move more cars, as opposed to what can be done to move more people.

Seattle’s bus system is due for a big impact with the closure of the Alaskan Way viaduct, to be sure. SDOT touts added trips coming in September as a result of transportation benefit district funds, but added trips won’t do much good if they are stuck in traffic, and a lack of dedicated right-of-way for most bus routes means fewer trips than we could be providing as service hours sit in stop-and-go.

The RapidRide C, once it shifts to surface streets from the Alaskan Way viaduct, will have an extra 10 minutes added to its scheduled time between downtown and West Seattle, increasing from 25 minutes to 35 between 3rd & Pike and Alaska Junction. Increasing that time even further due to congestion will make that trip noncompetitive with driving, increasing the cycle of congestion. SDOT has added a bus lane to 4th Avenue S in SoDo that doubles as a turn lane, but routes elsewhere lack even this.

Four billion dollar @BerthaDigsSR99 boondoggle delayed yet again.

— The Urbanist (@UrbanistOrg) September 17, 2018

🚨 3 years behind schedule.

🚨 $600 million over budget

🎣 Seattle/WA could be on the hook.

No officials complain BECAUSE CARS. #DoubleStandard #CarCulture https://t.co/mRpuCjXXWX

The 3rd Avenue bus corridor, now that it is transit-only all day, should be a safe haven from congestion delay, but SDOT does not mention enforcement on the busiest bus mall in the country. Instead, they state that SPD officers will be on hand to, you guessed it, help drivers: “We’re coordinating with the Seattle Police Department to deploy uniformed police officers at key transit intersections–prioritizing transit and helping drivers get through.” Prioritizing transit in a general purpose lane, of course, means prioritizing all traffic.

SDOT also says they intend to restrict construction closures of certain streets in the downtown core during the three-week SR-99 closure in order to maintain car lane capacity. Imagine if the same policies were in place around sidewalk closures in downtown, including developments like the Rainier Tower project that removed a sidewalk in the middle of downtown on both 4th and 5th Avenue, forcing pedestrian traffic to the other side of the street.

With no added emergency bus lanes, and no additional places for people to safely bike, and even no guarantee of safe walking infrastructure, the period of “maximum constraint” remains a missed opportunity to chose not to attempt to cram as many vehicles onto Seattle’s downtown streets during the middle of a climate crisis. It remains to be seen exactly how effective the city’s strategies for dealing with this challenge will be, but whether they luck out or don’t, we won’t be any closer to realizing the city that we wish we inhabited.

One Center City Is Now Imagine Downtown

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.