A year after the city adopted new vacant building maintenance and demolition laws, the city council received a monitoring report and briefing on the program. The report outlines several recommendations to improve the program. Last year’s ordinance was particularly notable because it sought to strengthen requirements for securing vacant buildings, expedite cleanup processes, and speed up the process for demolishing hazardous vacant buildings.

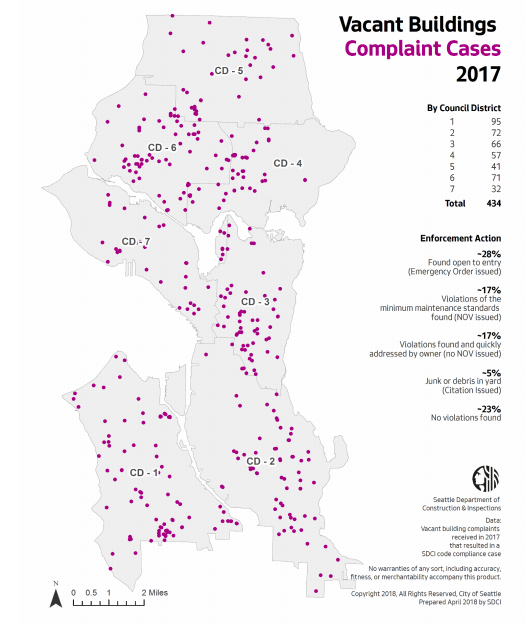

The report indicates that vacant building complaints have shot up 64% since 2013. While there is a noticeable concentration of complaints in Urban Centers and Urban Villages–as one might suspect–complaints also frequently appear in single-family areas. However, the report indicates that since vacant buildings complaints seem to be largely equally distributed across the city, they are not having a disproportionate impact on historically disadvantaged communities. In other words, the prevalence of vacant buildings does not seem present a concern from the equity standpoint. For economically disadvantaged building owners, however, there is an equity challenge in terms of their ability to maintain their property and pay inspection fees and civil penalties.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold disputed some of SDCI’s analysis and noted that there were high concentrations of vacant buildings in disadvantaged communities like Roxbury Heights in her district, particularly ones not enrolled in the monitoring program.

The report outlines various policy choices for the city council to consider in order to improve the program. The policy choices fall into six distinct categories:

- Enrolling vacant buildings in the monitoring program;

- Revising maintenance standards;

- Adjusting fees;

- Adjusting civil penalties;

- Building valuation; and

- Temporary caretaker program.

Enrolling vacant buildings in the program

In the first year of the new program, 43 properties were enrolled into the vacant building monitoring program. These buildings were enrolled due to lack of maintenance by the property owners after a violation notice. Typically, these buildings are not associated with a development project. Monitoring of the buildings occurs quarterly by SDCI inspectors, except for the highly troubled properties where inspections and site visits occur more frequently.

Trouble properties are investigated by the Seattle Police Department and Seattle Fire Department after complaints or emergency calls are made to 911. Under new authority from last year’s legislation, SDCI can eventually begin the process to commission demolition of the building without the property owner’s agreement if the frequency of safety and health violations complaints remains high. Unlike buildings enrolled in the vacant building monitoring program, there is no fee assessment on the property owner by emergency department investigations. In other words, response to the complaints are free despite the investigations occurring essentially in an informal two-tiered program, which was a point of contention by Councilmembers Lisa Herbold and Mike O’Brien.

SDCI outlined several options to more easily enroll vacant buildings in the monitoring program, such as any complaints, violations, or health and safety concerns. Other policy options could involve instances where there are no complaints or violations, such as upon foreclosure, vacancy, or redevelopment.

Revising maintenance standards

Under current law, the city can require that vacant buildings be maintained in a good condition and property secured to prevent unauthorized access in accordance with the Housing and Building Maintenance Code. In some cases, the city can impose higher standards to ensure that healthy and safe conditions are maintained. However, many small issues are overlooked through the inspection process.

To improve maintenance standards, SDCI offered several options, such as changing business practices for more aggressive enforcement, modifying and strengthening standards in code, targeting problem buildings with additional standards in code, and targeting long-term vacant building with additional standards in code.

Adjusting fees and civil penalties

A major struggle for SDCI with monitoring fees is the low payment rates by property owners. While fees typically range from $250 to $500 per visit quarterly, many property owners choose not to pay the fees once they have been invoiced and sent for payment. Eventually SDCI contacts a collection agency to collect fees that are due. Often that too is not successful, but even when it is the collection agency takes a large share of any collected payments. If fees are not paid within several years, SDCI will retire the outstanding debt. Civil penalties are a rare and costly process.

To remedy the issues with funding and compliance, SDCI outlined several options to modify the approach to fees and penalties, including:

- Lowering monitoring charges for properties deemed in compliance;

- Raising monitoring charges for properties that fail to improve and present repeat problems;

- Increasing civil penalties for properties that don’t respond to notice of violation;

- Change business practices to improve overall programmatic cost recovery;

- Increase the frequency of monitoring for problem buildings, which would require higher staffing levels and probably wouldn’t help with cost recovery; and

- Evaluate other ways to reduce vacancy, such as increasing demolition permit and development application costs for properties that been vacant for a long time.

Building valuation

One way that SDCI determines if a property is deteriorating to the point that needs city intervention is through a building valuation method. Declaration of such allows the city to order the property owner to repair, vacate and close, or demolish a structure. Under the current assessment process, this can often be a time-consuming and impossible task to complete prior to a building deteriorating to such a degree that is simply unfit for human habitation and a serious public safety threat. This is particularly problematic when it comes to assessing building interiors.

To expedite the building valuation process to make orders sooner, SDCI has suggested several options:

- Revise business practices through better technology and software, updating the valuation schedule, and different assumptions to determine market values for repair;

- Develop an alternative process for building valuation of severely unfit buildings;

- Require self-reporting by property owners on the condition of buildings when they become vacant;

- Explore possibility of mandating a more detailed inspection

Temporary caretaker program

SDCI is in the process of developing a temporary caretaker program that would connect property owners of vacant buildings with human service providers that would identify temporary caretakers to live on the properties. Conceptually, SDCI would use a model similar to that of Weld Seattle with the hope that this would avoid the negative impacts and costly nature of vacant buildings on the city while providing temporary housing for individuals and families that might otherwise experience homelessness. A similar program is being pursued for industrial and commercial space that would provide temporary space for arts and cultural uses.

SDCI laid out three primary policy choices for this program:

- Proceed ahead without code changes as a voluntary program;

- Pursue code changes that either incentivize participation (e.g., tax waivers) or directly require participation; and

- Developing incentives that encourage property owners to keep existing residential tenants on-site, such as offering permit processing priority.

The next steps on this vacant building monitoring program effort will involve further review of the options and feedback from legislators before SDCI develops formal code amendment proposals for consideration, possibly as early as next year. Some of the administrative changes, however, are already underway or could be implemented sooner.

Council Moves Spruce Street Rezone, Demolition Ordinance

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.